INTERVIEW

Glory and Contradictions

WILLIAM MARK SOMMER

An interview with William Mark Sommer

“I truly hope we all can make it through this and be able to come together across the world for the betterment of human kind and the world in general.”

William Mark Sommer is a film photographer residing in Sacramento, California. Mark has earned his BFA in Photography from Arizona State University and he has exhibited over the United States and Internationally. In 2020 Mark was picked by Alex Prager for Life Framer’s “Open Call” First Place Award. Mark also has self-published 10 zines and has been featured in publications like Stay Wild, Float, Aint Bad, Booooooom, Analog Mag, The Modern-Day Explorer, among others.

Within Mark’s series he utilizes a long-term documentary mode of storytelling to explore themes of human nature, preservation and empathy. He photographs to further his understanding of a diversity of human experiences, exploring what we hold dear and how our actions shape our environments. He looks for his work to challenge stereotypes by showing the unseen and giving a voice to the misunderstood.

Hi William. Firstly, congratulations on winning our Open Call. What did you make of the judge Alex Prager and the Life Framer team’s comments?

Thank you, it still feels surreal to win the Open Call. I am truly honored to be selected by Alex Prager and to have her write about my photo. Both Alex and the Life Framer team touched on exactly what I was going for within the photo, and I am gracious to both of you for their kind words; this truly made my year. Thank you Alex and Life Framer.

I understand it’s from your series “Dusted”. Can you tell us a bit more about that, and the specific origins of this winning image?

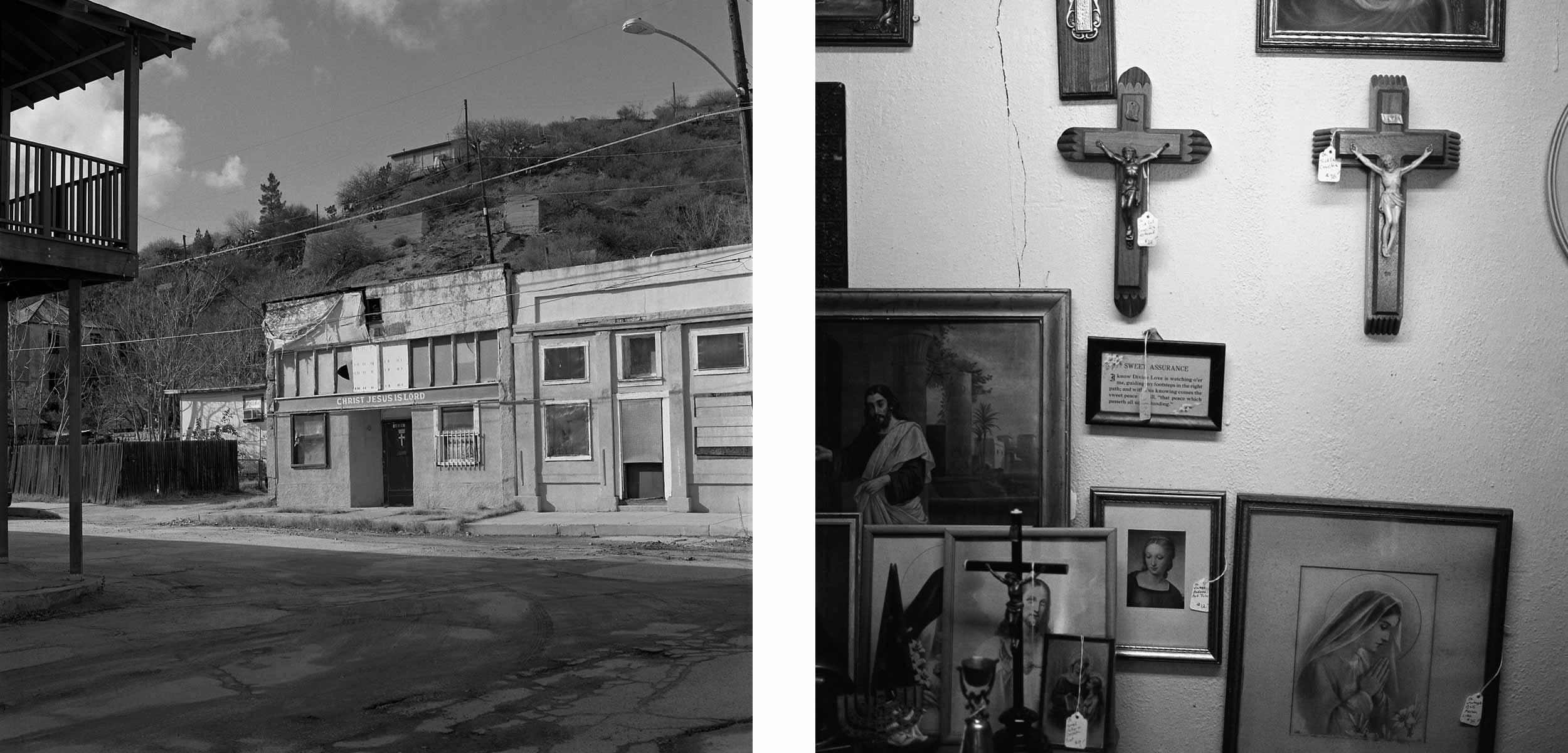

Yes, Dusted is my series that questions the whitewashed narrative of America’s mining history, a version too often presented in history books and local museums. Knowing that mining is destructive by nature, experiencing what this process has done to the earth, and spending time with the people who are forgotten as mines deplete resources, shutter, and move on; I was driven to tell this story. As the sprit of Manifest destiny is continued within the ever-expanding mining industry I look to reveal what was left in the wake of false promises and hopes.

The Lone Cowboy photo came early within my initial exploration and developing phase in creating “Dusted”. When intuitively creating within Monument Valley, I drove up this scene of a man riding a horse to the edge of the cliff as if he was going to go over the edge into nothingness, but the horse stopped suddenly in wait, petrified on the edge as a group of tourist run up and the cowboy dismounts making room for the travellers to have their picture taken like they were John Wayne. When coming home and developing the negatives I was drawn to the complexities of the photo and how it conveys this perceived glory and contradictions of history. This location in Monument Valley is known as Ford’s Point, after the director John Ford who utilized the it for his westerns about how the west was won, and like propaganda, these Hollywood depictions shaped the way history was seen and created this imagined artefact of the west. Detailing these visions of Manifest destiny within the photograph, I look to convey the looting of land these original pioneers perpetrated and to have the photo stand as a metaphor for the many Native lands are being once again seized by the government for mining purposes.

I’m always interest in where ideas for series come from. What was the genesis for Dusted?

I feel that the ideas of Dusted were always with me from my childhood, growing up only 20 miles away from where the California Gold Rush started at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, meant for a heavy handed history of mining through my early schooling. The way this history was taught through the 90s was a very basic concept of dates and the glory of America’s plunder, but never the human stories of struggle and death that came through the effects of mining. Through this white washed narrative I was fed, I always wondered were the truth was.

Moving to Arizona, I was able to see these affects of mining first had within the many mines and abandoned company towns that pepper the landscape. Seeing the loss of people’s livelihoods and the ecological damage that never gets spoken about or even repaired drew me to create Dusted. As I met more people, visited more forgotten towns and saw the consistent destructive nature of these mines and their effects on the future empowered me to keep pursuing this series.

These personal experiences in the field and childhood history lead me to extensive research in both the history and the recent studies and news regarding mining. It was interesting and haunting for me to seemingly walk through the shoes of Charles D Poston as he made his way across the nation and into Arizona to create its first American mines which helped make Arizona into a state in his book Building a State in Apache Land. Websites like www.abandonedmines.gov and www.arthworks.org were great resources in helping me discover the treatment and show the vastness of these superfund sites and abandoned mines. All of my experiences, research and personal history went into the creating and execution of Dusted.

And you chose to shoot exclusively in black and white. Why was that? Was it about evoking this history?

When I was starting through my exploration into shooing Dusted I used equally both color and black and white film, but as I continued, black and white became the right fit. During that time, I was looking for a change after creating the majority of my previous work on color film, and in Dusted the initial color work felt forced and played into the aspect of color significance over the project. By shifting to black and white film only, my focus became inseparable from my topic and thesis when creating in the field and expanding the series into what it is today.

Though these aesthetic choices might be minimal, creating in film brought a closer tie to mining within the silver salts that make up the film base, and the fact they come from the same process that I am critically showing.

Perhaps you can tell us about one or two more images from the series?

This photo “Chopped Mountains” is of the Morenci Mine from the side of the highway that stretches through the length of the mine. This looming mountain shows the true affects of mining to scale as each truckload breaks down this mountain. The Morenci Mine is one of the largest copper reserves in the world and one of the largest open-pit mines in all the US. By utilizing the Morenci Mine, I look to show what active open pit mining is like while giving measure to describing destructive process.

Following the history of mining at Sutter’s Mill, I took it upon myself to experience what these people felt within the river. Though I will never know the cost and trials of what it took to make it to California, I felt it was important to grasp the struggle of digging in the icy cold water and then hours of back and forth panning only to come up with nothing. The amount of effort and strife these people went through in the 1840s was astronomical, and though many books dictate these struggles, it means more to me feel at least this one small part of the struggle they went through to survive and make a life for their families.

As with Dusted, much of your work confronts American history, culture and identity. In these particularly tumultuous times, do you feel positive about where America is heading?

Unfortunately no, I love America, it is my home, but as Covid-19 took hold, so many of the same mistakes of history were repeated. It saddens me to see what has been going on through all of this, between strife and lockdowns, and with disenfranchisement at an all time high; I feel at a loss most days. I would like to stay positive and give hope, but many things were at a breaking point prior to Covid-19. Through creating Dusted, I experienced so many people come on hard times, lose their business and jobs, have to abandon their homes, all in the name of corporate greed, and everything seems to be compounded even further with Covid-19. I truly hope we all can make it through this and be able to come together across the world for the betterment of human kind and the world in general. I feel that this quote by George Santayana, is important to remember right now; “Progress, far from consisting in change, depends on retentiveness. When change is absolute there remains no being to improve and no direction is set for possible improvement: and when experience is not retained, as among savages, infancy is perpetual. Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

You studied photography at Arizona State. How was the university experience? What do you think you get from formal study, versus a self-taught approach?

My university experience at Arizona State had its ups and downs. Coming into a program to finish my degree in my late 20s, I felt like an outsider between many of my colleagues, but receiving the opportunity to work with such a great faculty in Mark Klett, Binh Danh, and William Jenkins; they helped me grow as a photographer and artist in ways I never conceived possible. Creating within ASU also gave me the time and critique to refine my practice beyond previous understandings. As a photographer who has spent time outside the university and in a couple different ones, I felt when I wasn’t apart of a university I was lacking the critical feedback to see outside my own work and grow further as an artist.

I admire people who are able to develop a successful practice without the need for a university. Being self-taught without mentorship and critical feedback I think is a more dangerous thing, those two social aspects are extremely important in avoiding the pitfalls of being a young photographer. Being self-taught is still the main process within universities too, people need to take an interest in their education to get something out of it, and grow within it. Being within the university helps ease the transitions of life and gives people contact with others who are professionals and their peers. It’s important to do what’s right for yourself, and to feel passionate and driven to do the best you can in either scenario; that’s the best way to success.

And as a teacher now yourself, what lesson do you wish you could give to your younger self, or someone just starting out in documentary photography?

One thing I find important right now when trying to manage life in Covid-19 times is, hang in there. It is really hard looking at what is going on right now with any end, but I feel it is important for students and everyone to know, don’t give up.

When thinking of advice for someone starting in documentary photography, convey your truth within your work, believe in the art you make and don’t feel scared to talk to people or ask someone for their picture, all they can say is no, and most of the time people say yes.

And finally, what’s keeping you busy right now? What’s inspiring you?

As I write this, I am currently on a road trip across the Loneliest Road in America trying to further my research into my Dusted project by visiting more mining towns across Nevada to try and tell more of this story. While continuing to try and safely travel, when home, I have been creating book dummies of my on going projects, experimenting with sequences designs and adding new work as it slowly comes in, has kept me creatively fulfilled and motivated within these many shutdowns. I have been feeling inspired by many the photo books I have found over the lockdown and also in reading Robert Adam’s “Why People Photograph.”

All images © William Mark Sommer

Follow him on Instagram @williammarksommer and see more at www.williammarksommer.com