INTERVIEW

Body and Structure

WITH ODO HANS

An interview with Odo Hans

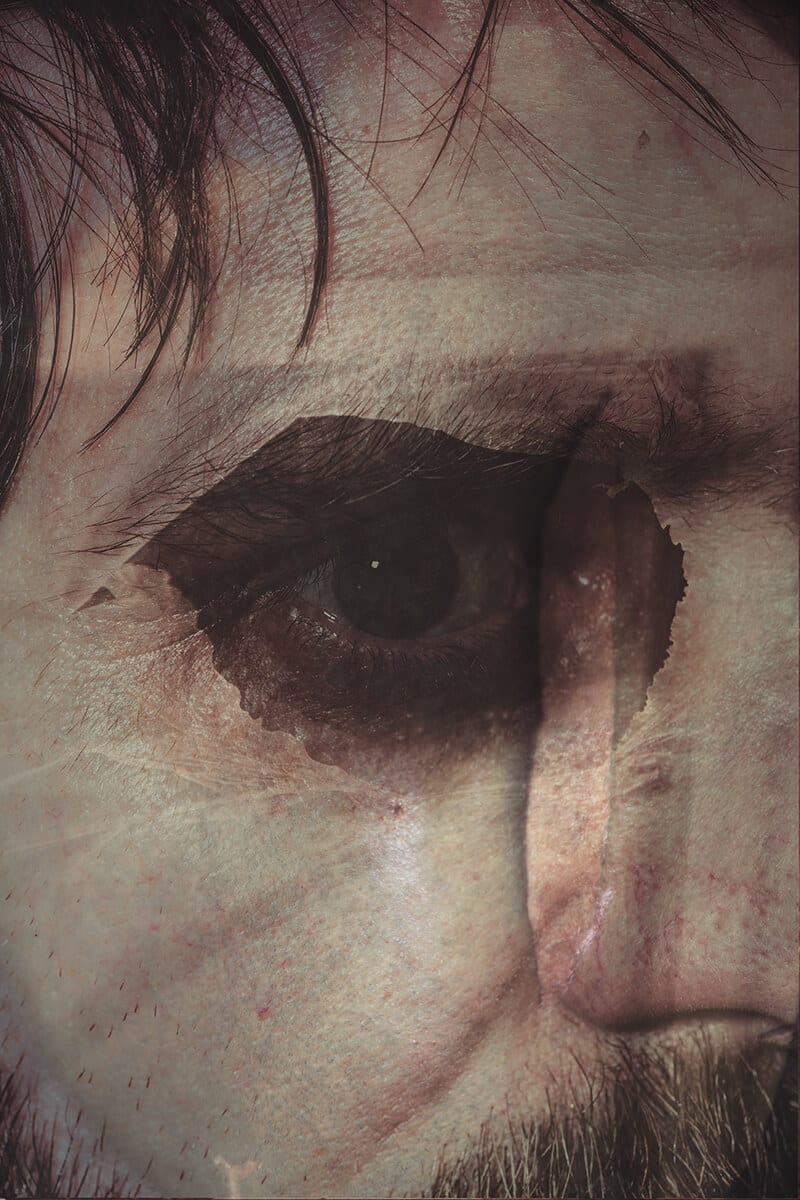

“I began to construct a world that shows reality as a self-referential system, in which man constantly examines, feels, and steps into himself”

Odo Hans won our theme ‘THE HUMAN BODY’ – judged by Alison Morley of the International Center of Photography (ICP) – with a challenging digital mash-up evoking myriad ideas about our cognizance of the human body in the modern world. Alison described it as “a dynamic ingress to the human toll or perhaps the bedraggled curtain of life” and it seemed like an apt jumping-off point to ask Odo about the image and the series from which it was taken and his working process. His responses are educated and fascinating, taking us on a journey through genetics, beauty and the very fabric of perception itself.

Alison saw in your image a struggle – against ageing, against our inevitable mental and physical deterioration. How do you react to those comments?

It shows that, in her interpretation, Alison Morley does not bring to bear deciphering hermeneutics but offers an interpretation that makes available the joy in the image and experiential potential of this work. In one way, her interpretation varies from the “real” events of the image, as although the eye is that of a woman, the face belongs to a man. But there’s potentially a struggle against ageing in this combination too, of course.

The image is from your series ‘EPI’ – in which you create surreal-looking ‘skinscapes’, pairing organic, human details with man-made surfaces. Can you tell us a little more about the series – how it came about, and what you hope to convey?

I worked on a project on the theme of the human body before I started work on the series EPI. Here, too, my concern was about the de-automation of visual habits, but I was trying to achieve this purely at the level of lighting and the perspectivation of skin. I wanted to go one step further, and so I had the idea of hybridizing body and structures, using elements that are alien to the body. So I began to construct a world that shows reality as a self-referential system, in which man constantly examines, feels, and steps into himself, walks on his own objective trails and, in the coincidence of spatial body and body space, is confronted with having to process the increase in information.

Odo’s winning image for ‘The Human Body’

Many of the images are somewhat unflattering, and along with the introduction of man-made textures create something a little unsettling, uncomfortable. I’m drawn to contemporary themes of human augmentation, android technologies and the ‘uncanny valley’ – the human 2.0. Are those themes of which you’re also conscious?

Those themes definitely play a role. I would almost describe my works as derma-concretizing ones. Eternit-armoured foot claws, facial fragments with planar distortions and chest pads with cladded façades arise in them, for example. All elements of how one brings to bear modern relations of production and genetic creation fantasies which already pre-formulate the reality of tomorrow, or, respectively, already partly correspond, today, to the alien-like manifestations of some successful breeding programmes by modern geneticists.

And on that same subject of working with, or embracing, a certain ‘ugliness’ – is it a conscious push-back against normal notions of beauty? Do you feel that depictions of traditional ‘beauty’ have been taken as far as they can go?

Defining notions of beauty in general terms is extremely difficult, as deviations from the standard have always been present in tribal cultures and modern sub-cultures alike. The desire for difference or the embedding of religious rituals has always turned the skin’s surface into a stage for self-performance, for example through the application of decorative scars, so-called scarification. Forms of tattooing are a subjective contemporary variant of this.

Nevertheless there are, of course, conventionalized patterns of portrayal of dermal beauty. These days, skin beauty is often associated with immaculateness and smoothness. The same digital tools with which I, too, work are used for the same purpose at the same time. For the purpose of manipulation. The outcome, however, is a totally different one. In both cases though, a reality is constructed – their one allegedly strives for reality, whereas in my case reality and its duplication is ruled out.

In that sense, my constructions are also deconstructions of ingrained ways of seeing and subsequently, they absolutely do problematize categorizations such as beauty and ugliness. For beauty is often not true, and the truth is often not beautiful. Or, as Nietzsche radically put it: “The truth is ugly: we have art so that we do not perish by the truth”.

You refer to your search for ‘new ways of seeing’ and of a combination of digital and analogue methods. Can you describe your process for creating the images for ‘EPI’? Do you work with found elements, or is everything self-generated?

I do not really work with analogue methods in this project, but I do have recourse to darkroom techniques which I used to make my first photograms and double exposures in the past. I don’t use any templates but I do produce all images from which my compositions subsequently arise.

Most images from the object world arise in urban contexts. In this case I always had my camera with me on journeys, or I moved through Cologne, the city where I live, always on the search for certain textures. With time one often develops a feeling of what textures work at the visual level. For the most part I acquired the people for my project from my immediate surroundings. I then scanned their bodies from head to foot for structures that were peculiar to them. I then brought the various planes together in Photoshop. This process was sometimes very laborious and complex, but sometimes immediate as well.

The images certainly aren’t straight-forward, but they are not totally de-contextualized nor abstract – it is possible to identify a certain body part or feature in almost all of the images. Was this a balance you were aware of, to present the human surface as something strange and new, but still very much human?

It’s definitely important to recognize the human aspect in the images, but less at the level of purely identifiable human excerpts than in their coupling with the object world. In this fusion, the human quality of being able to get away from objects and recognize form unfolds independently of the objects’ normative attribution. As in a poem, in which one senses the meaning but without necessarily being able to explain it.

The final work is 42 images, all in portrait format. Is there some logic to this?

The upright gait conditions the portrait format. If we crawled on all fours, the landscape format would’ve suggested itself.

And finally, has ‘EPI’ impacted the way that you look at your own body, or others’ relationship with it?

Conditioned by the circumstance of having misshapen so many bodies, one begins to doubt one’s own form stability.