INTERVIEW

Fiction from the Fabric of Reality

WITH MICHAEL ERNEST SWEET

AN INTERVIEW WITH MICHAEL ERNEST SWEET

“The camera is a unique tool in that it does depict reality but you can select which part and how much of that reality to show. This is where the photographer gets to create fiction from the fabric of reality. The messy zone. The grey space. I love to work in that space.”

As long-time admirers of Michael Ernest Sweet’s street photography, we were delighted when he reached out for an interview — and the discussion that followed did not disappoint. Covering topics such as finding a signature style, consent and privacy in the public realm, storytelling, and the future of photography, it’s one of the most thought-provoking interviews we’ve ever run.

Read what he had to say on these topics and more below…

Hi Michael. Please introduce yourself in a few words, and perhaps a fact we should know about you.

My name is Michael Sweet but I usually go by Michael Ernest Sweet in the photo world, as there is another well-known photographer by the same name. He photographs underwater and I do not, so we aren’t often confused. I grew up in Nova Scotia, Canada, on a small horse farm. I’ve lived in different places, but I finally settled in New York City (for the time being) where I teach literature at a private school and moonlight as a writer and photographer.

What was your route into photography, and how would you now describe your photographic work?

My aunt, Canadian painter Susan Sweet, was an avid photographer while she was in her BFA program in the 80s. I was just a kid and I was drawn in by the allure of all the gear. Big, shiny chrome cameras and long lenses. She even had a small colour developer. She let me use stuff, even the then-coveted Pentax K1000. I was hooked. For many years I took simple “snapshot” photographs. Cats, dogs, trees, horses, flowers etc. While I was in college I began to photograph store windows. I guess this was my foray into street photography. When my father took his life in 2009, I returned to photography as a kind of therapy, I think, and my current style of work emerged. And stuck! My work could kind of all be described as “evidence”, evidence that humans were here. That is, I take photographs of people but not people. Just bits and pieces of people. Evidence of people. My concern is with people in the abstract – the universal person.

Like a lineage of photographers before you, you shoot predominantly on the streets of New York, but bring your unique perspective – capturing something of the eccentricity, intensity, and perhaps claustrophobia of the city. How did you develop your signature style?

My signature developed rather by accident. New York City is claustrophobic. People are everywhere and we are cramped in together. It is hard to make clean frames. So I really just leaned into the idea of shooting people up close and with the idea of making cluttered and odd frames. I found interest in this kind of image was enhanced by portraying people in deliberately odd ways, showing people in ways that we do not actually see in real life – with heads lopped off or from the nose down only – things like this. The camera is a unique tool in that it does depict reality but you can select which part and how much of that reality to show. This is where the photographer’s influence on reality comes into play. This is where the photographer gets to create fiction from the fabric of reality. The messy zone. The grey space. I love to work in that space. My work is all candid and actual bits of reality but it all has a kind of surrealism about it as well. In terms of the way I see and the way I think about photographing, I’m most related to Mark Cohen and Stephen Shore. They have been huge influences.

I’m reminded of the well-known Robert Capa quote: “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” This close-up, cropped form of shooting developed organically as you note, but is it now a conscious choice?

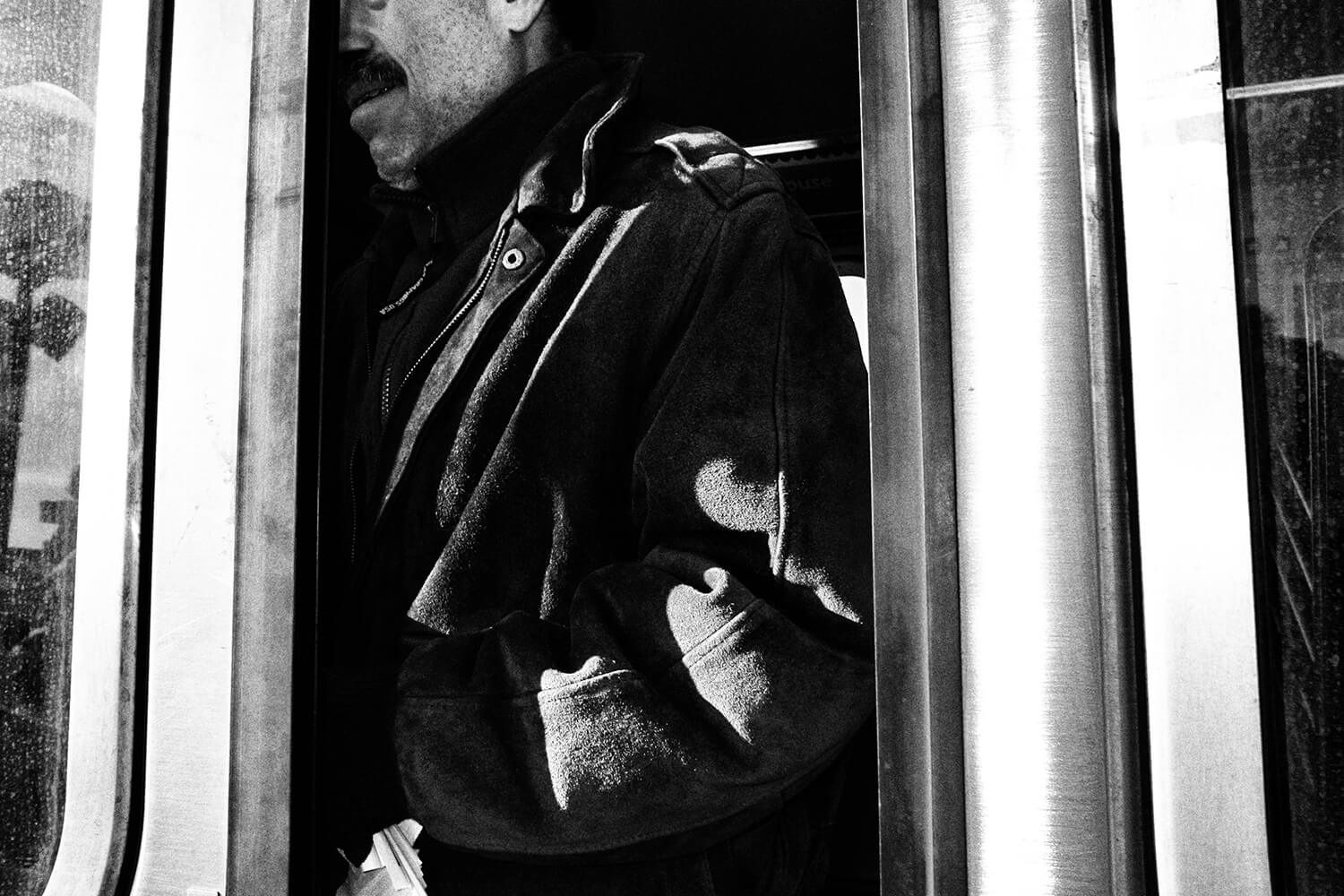

Not really. The city sort of forced me to work up close. I don’t actually crop photos, as in post-process cropping. I more correctly frame out certain things when I shoot. In one photo [see top image above]. I intentionally framed out the man’s eyes. I wanted his slight grin to really be the focus of the photograph. I also wanted his face to have some additional definition, so I included the bottom of his eyeglass frames but no eyes. Eyes steal the show and if I had included them the grin would have been diminished. This is where my Stephen Shore vibes come in – I really think about what I am including and not including in the photograph. It is sometimes very cerebral. Other times, I am more in a Mark Cohen frame of mind where I shoot more instinctively and quickly and then discover hidden “gems” later in the contact sheets. I don’t think one way is superior to the other. I think chance and luck are an undeniable part of photography no matter who you are or how good you are. I embrace both approaches and my body of permanent work is made up of images that were produced by both methods. Put another way, sometimes I make up the story and find the image and other times I find the image and then make up the story.

There are interesting debates about respect and consent in street photography – where subjects should be asked for permission, the degree to which personal space should be respected. What’s your view on this? How do you navigate what could sometimes be a confrontational pursuit?

Firstly, I don’t believe in privacy in public. I don’t think this really makes much sense. Obviously, there are a couple of caveats – some people do change in public (say, at a beach) and there are public WCs and things – one should have protection in these circumstances. But photographing people on a sidewalk I think needs to be permitted. I know a lot of countries don’t agree and I think they are wrong. United States law continues to reject the idea of privacy in public to the point of even allowing people like Arne Svenson to photograph through people’s windows if the curtains are open. I think this is a good thing. It helps to reaffirm that the public space is a communal space – a space where one cannot dominate with individualism. All of this said, I still obviously get into the occasional confrontation, although it is a rare occurrence. I think many years of experience has taught me to spot those situations before I photograph. Interestingly, I’ve never shot a “confrontational” subject and made a fantastic photograph. This kind of person always makes the worst subject.

With such an instinctive approach to your street photographer, what if any degree of planning is there? What’s your workflow?

There is a lot of instinct, yes, but it is not all that way. There is also a lot of thinking. A lot of my photographs don’t make immediate sense to a lot of people. But when you stop and think and really look, things begin to come into focus. Take the photo with the guy between the doors, for example [see top image above]. This photo may seem unremarkable at first blush but there is a lot of good stuff going on. The guy’s face, again, no eyes to steal the show but enough moustache, chin, and nose to give him character and personality. The multiple vertical lines of the doors add strong graphic definition. Finally, the glass in the doors, parallel on each side, reflect a sliver of non-descript urban landscape. I saw the scene but only later appreciated the photograph for its mysterious quality. Other photographs like the twins in the stroller [see second from top image above] involve much more luck. I saw two kids and thought let me leap in front of them and fire off a shot. Only later did I discover that they were actually twins, which, of course, is what makes the photograph work.

Why black & white?

I do shoot some colour. I have a book, Michael Sweet’s Coney Island, which is all highly-saturated colour photographs made with a Japanese toy camera (the Harinezumi). I don’t shoot a lot of colour though, as I find it a distraction to my way of seeing. I don’t really see in colour when I see in photographs. I look for subject matter and composition – lines, light, shadow, shape, etc. Colours are really last in my mind. They are distracting, for me, in the final print, too. I don’t want to put down colour photography, a lot of people obviously find it rewarding, but I try to make images that are strong enough in other ways that they simply don’t need colour. Learning to see in black and white has unquestionably made me a better photographer. I would also add that I often don’t like how cameras (especially digital) render colours. And, as I am not a fan of complex post-processing I don’t care to have to recreate the photo I want on a computer.

Can you pick out a shot you’re particularly proud of, or perhaps has a particularly memorable story behind it?

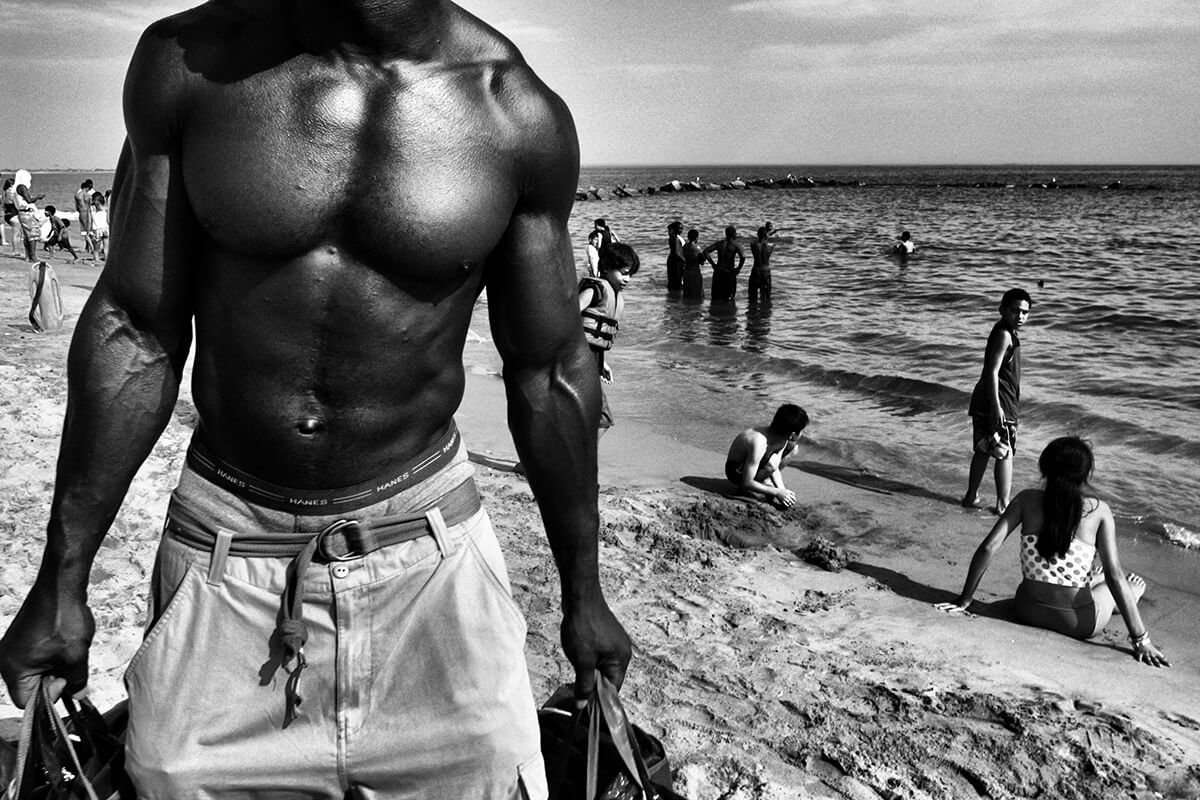

Let’s see, I have talked about a couple of photographs that have elements that illustrate my style etc., but to select one that I am really proud of is a lot harder. I think the photo of the over-tanned man on the beach with his arms stretched out stands out to me a lot [see top image below]. It’s not so much that I am proud of it, but more that I am really pleased with it. It’s a candid photo and it was hard to make such a photo on a beach with a 28mm lens and still get, essentially, right on top of the man. His arms stretched out are a strong graphic element that pulls the eye across the entire frame. The perfect triangle between his ear, shoulder, and chest is also another bit of good luck. Many stars aligned when this shot was taken – a single shot, too. I often don’t take multiple shots and this was one of those times. I got what I got and what I got happened to be good, really good!

You’ve mentioned Mark Cohen and Stephen Shore as influences. Do you have any other photography heroes, or perhaps inspiration from other areas of life?

I know Mark Cohen and Stephen Shore personally, so it is harder to think of them as heroes I guess. Certainly, I have tremendous respect for both of them and their work. Honestly, I don’t take a lot of inspiration from photographers. I tend to draw on a wider array of influences. Woody Allen’s films, Italian cinema – writers like Susan Sontag, Charles Bukowski, and Kurt Vonnegut – as well as painters such as David Hockney, Alex Colville, and Mark Rothko have all influenced me and therefore my work in some way. I also always like to mention Joel Meyerowitz in this conversation. Joel told me early on in my career that my work was ugly. He was very frank with me. He said that there were so many beautiful things to photograph in the world, why focus on the ugly? Although not exactly a compliment that conversation changed me forever. It made me examine my work in a new light and to really think about what kind of art I was creating and putting out into the world. Joel also referenced my work using the words “human fragment” in that conversation. Later, I published my first book under the title, “The Human Fragment”. Criticism can often be more useful than compliments.

You mentioned your job of teaching English Literature. On the surface there might not seem to be any parallels between street photography and this pursuit – but are there for you? Does one compliment the other in any way?

Yes, writers absolutely influence the way that I see the world – this capacity is the beauty of literature. I think being a literature teacher, as well as a writer, has also allowed me to develop the way in which I think about photographs. When you take a photograph and begin to think about how you might describe it, write about it, talk about it – you begin to see the photograph with more clarity, precision, and intellectual depth. Writing about my work has allowed me to appreciate its complexity in a way that I would otherwise miss.

With the evolution of social media and the advent of generative AI, do you feel hopeful about the future of photography?

I do and I don’t. Let me explain. I think photography is changing rapidly. Soon, the photography that I knew when I was a kid will, more or less, be gone. People simply don’t consume photographs in this way any more. Photography is now more of a language. You asked about the connection between literature and photography, if any, and I think this link is becoming stronger and stronger. We now tell stories, whether formal or informal, through images. Photographs are a linguistic tool not merely an artistic one. In fact, I think they will become less and less artistic. I know it sounds pessimistic but I think photography, as an art form, has already had its moment in the sun. I don’t think photography or photographs are going away, we know that’s not the case, but the way we look at them and appreciate them is changing. Photography is becoming more important for us, in a way, but also more ephemeral too. Galleries are losing interest, publishers are losing interest because the public is losing interest. When we consume 1000s of images a day on our Instagram feeds, for example, it becomes hard to then see value in a photograph as art. At least this is the way I read the scene. Perhaps I am wrong. Perhaps there will be some kind of renaissance for photography as art. That would be nice.

And finally, what’s the best piece of advice you’d pass on to your younger self if you could?

Take it all much less seriously.