INTERVIEW

Unclear, Disputed and Often Denied

WITH SHARON RITOSSA

During winter and spring 2016 Sharon Ritossa searched for and took photographs of foibe, deep natural sinkholes typical of the Karst region, situated along the Italian, Slovenian and Croatian borders. At the end of World War Two, the foibe of the Karst were used as mass graves to hide the bodies of Italians, Croats, Slovenians and Germans killed for political reasons. Today, the history of these deep cavities is still unclear, disputed and often denied; the foibe continue to hide secrets. This photographic research aims at reflecting on how the geological structure of a geographical region can affect its social and historical events.

Interview Sharon Ritossa, “Foibe”

What is your new project, Foibe, about?

Foibe is a project I did while on residence at Fabrica, the communication research centre part of Benetton group. During winter and spring 2016, I travelled along the Croatian, Slovenian and Italian borders to find foibe, sinkholes in which, during and after World War II, the bodies of Slovenian, Croatian, Italian and German political victims were thrown.

Who were these victims?

There were ethnic and political ones. The region of Istria, until then Italian, became Yugoslavian in 1945. Yugoslav partisans carried out an ethnic cleansing against the local Italian population, who form the majority of the foibe victims. Opponents to the communist regime in Yugoslavia were also killed, their bodies sometimes hidden inside foibe. Besides, a lot of victims were of the Istrian exodus: after Yugoslavia acquired Istria, Dalmatia and Fiume, some 350,000 Italians from these regions fled to Italy.

The history of the foibe is still unclear and disputed today. How did you undertake the research?

My undergraduate thesis was on the Istrian exodus. I studied the foibe for a year in the IRCI, a museum on the Istrian and Dalmatian cultures in my hometown of Trieste. But when I was doing research, the number of victims was always different depending on the historian’s political side. Some politicians from both left and right-wing parties have been conveying misinformation about the massacres for political gain for years. The more the numbers varied, the more frustrated I was becoming.

So the exact number of victims is still unknown?

According to the Treccani (ed. note: the Italian Encyclopaedia of Science, Letters and Arts), there were between 4,000 and 5,000 victims in total. But, in recent years, I was frequently reading in local papers from Trieste that new bodies had been found in a foiba – sometimes as many as 2,000 at once. These investigations still happen today as they take time and are very costly.

How did you overcome all these conflicting informations?

I decided not to work directly with historians as they all had a bias and I didn’t want to let myself be influenced. I chose instead to stay close to the people who really know the territory. I spent a lot of time with forest guards, who have been witnessing these massacres for generations. I heard stories of guards taking bodies out of the cavities themselves, sometimes hundreds. I wanted to show how the geological aspect of an area can affect its history. That’s why I decided to focus on the foiba (singular), the speleological term, rather than the foibe (plural), directly linked to the massacre.

The project’s name, Foibe, is plural, though.

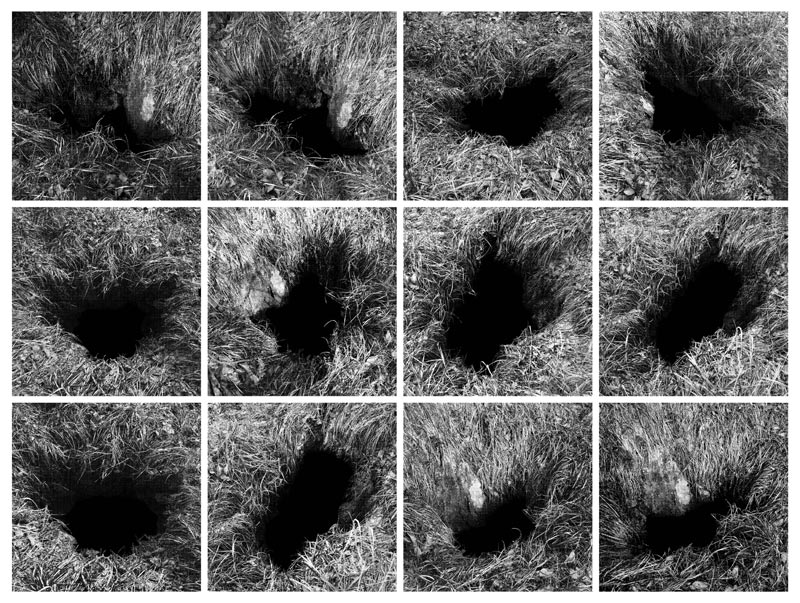

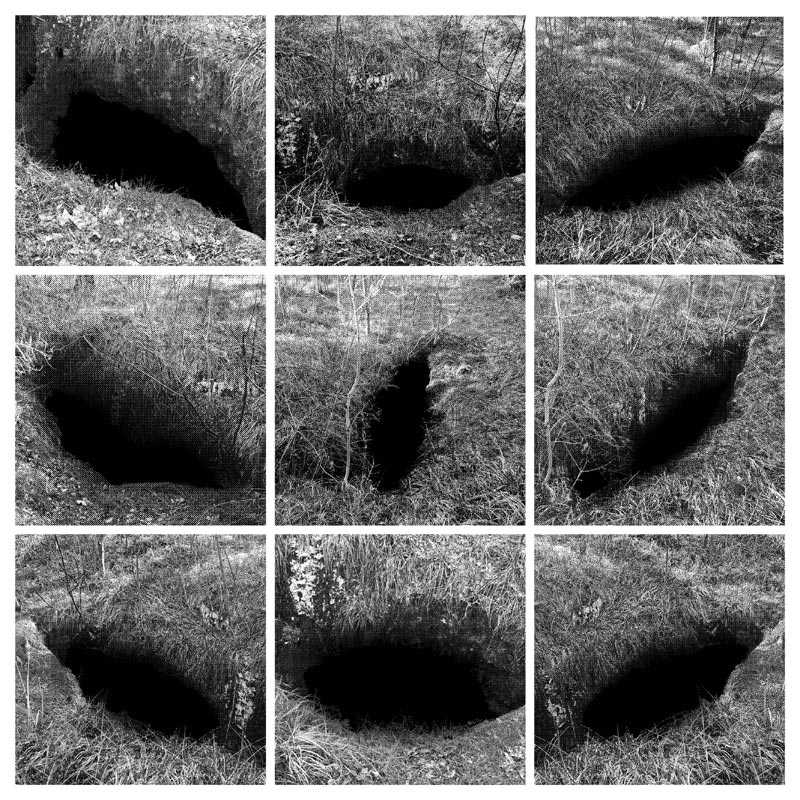

Yes, but when you see the pictures, you see the foiba, not the killings. You see the geological holes in their natural form. The images only make sense once you know what happened in each individual cavity – I only photographed some in which we know people died.

How did you locate them geographically?

The speleologists I worked with have a cadastre with the latitude and longitude of all the caves. Some were not exact, in which case I had to look for them by foot myself. It was a powerful experience for me: when you find a foiba, you don’t simply see a hole but a tomb hidden for decades, and in that very moment you know you are here to give the victims a memory. The cave in general is a strong symbol, in mythology and religion: it’s where birth, rebirth and death happen. For me, on a human level, caves are a metaphor for life. Going inside provides a strong feeling, similar to that of entering a temple. Even if you’re not religious, there is always this sort of fascination.

So you went inside some of them?

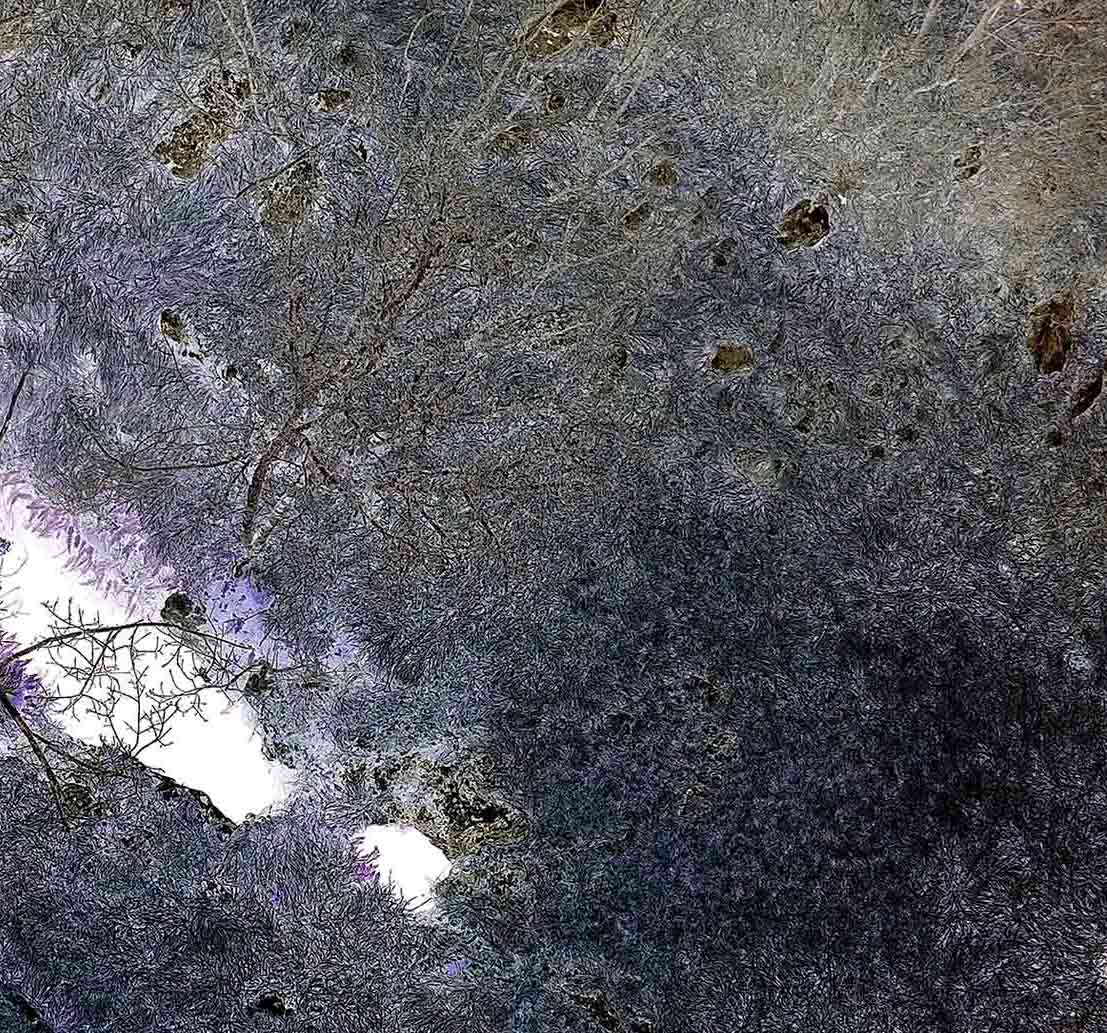

Only one, with the speleologist. Inside, there is very little light, it’s almost pitch-black, so I photographed the void. I asked myself: “Did I find the truth? I can find only the dark.”

So with this project, you wanted to shed light on this darkness – metaphorically and literally.

Of course, I did this project to try to bring more truth – obviously not the absolute truth – on this black page of history. A photograph is not a reality, it is merely similar to reality. I did not want to demonstrate but simply to show, to show what Italy refused to see for sixty years. This is why I photographed each foiba in a different point of view. I wanted to say that everybody – historians, speleologists, locals, politicians – looks at the foibe from a different point of view but nobody finds the ultimate truth, for one reason: the truth is inside, but inside there is nothing but the dark. So the subject is not the shape of the hole, nor the grass surrounding it. The subject is the dark itself.

This leads me to ask about the aesthetic choices you made. All the pictures are in black and white and converted in halftone; was it important for you to have black as the main consistent component of the photographs, almost as their protagonist?

Yes, that was one of the reasons. On top of that, I made the three main visual decisions in the project – black and white, halftone and screen printed – because they all remind of the first photographs ever printed in newspapers. There has never been an reportage on the different foibe in newspapers. Some individual archive images had been published, but no photographer mapped all the foibe in the Karst region. Besides, I thought the halftone was fitting for another reason: the image appears differently from near and from afar. In order to really see the picture, you need to step backwards. I think it’s analogous to trying to understand history: you need time and distance to take things into consideration and reach a state of detachment necessary to make sense of what happened. I think we can – and it is time to – understand the foibe more clearly today as more than sixty years have passed.

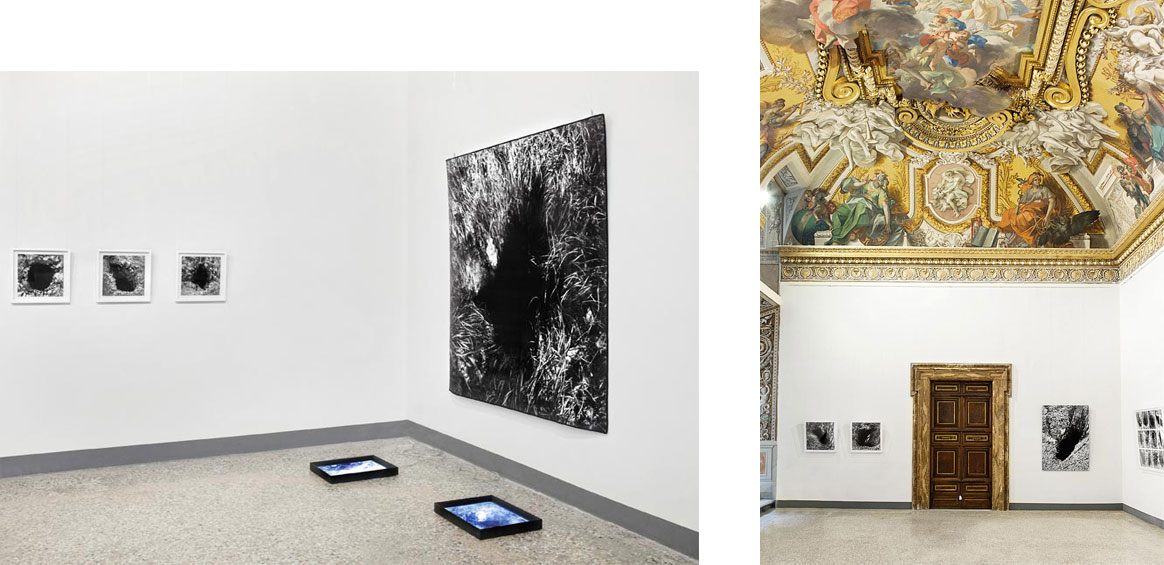

Foibe is currently being exhibited in Rome. How did you approach the pictures’ transition from paper to the gallery wall?

The main changes are in the varying points of view. In the volume, each image is of a distinct foiba from the point of view of the photographer on the ground, while in the exhibition there are less foibe but three points of view: from the photographer, from a drone and from inside. I decided to reverse the colours of the pictures taken by the drone and to display them on a lightbox, giving the impression that the light comes from the hole rather than from above it. It seems like you are inside the foiba and you look outside, from the victim’s perspective.

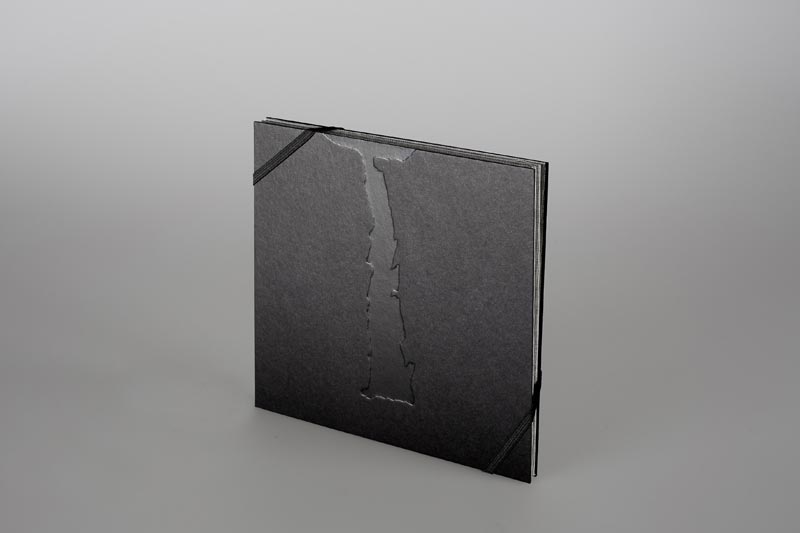

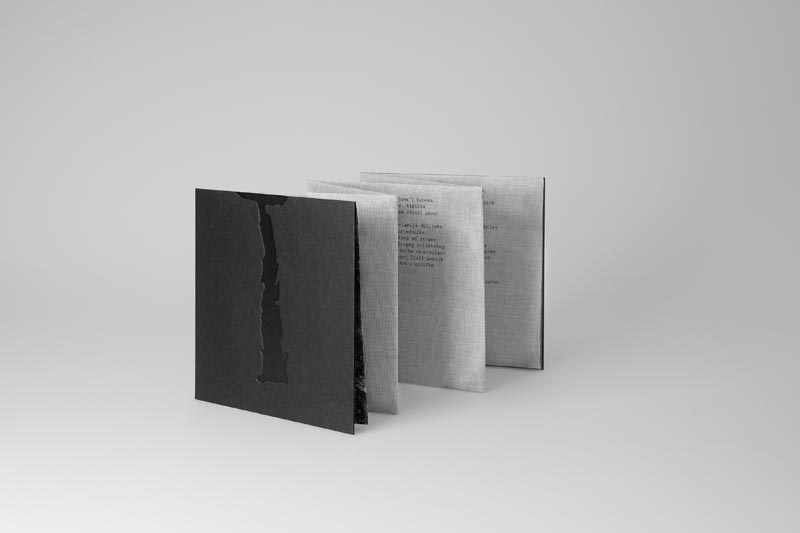

The publication Foibe is a folded screen-printed photographic map. Why did you choose this format rather than a regular book?

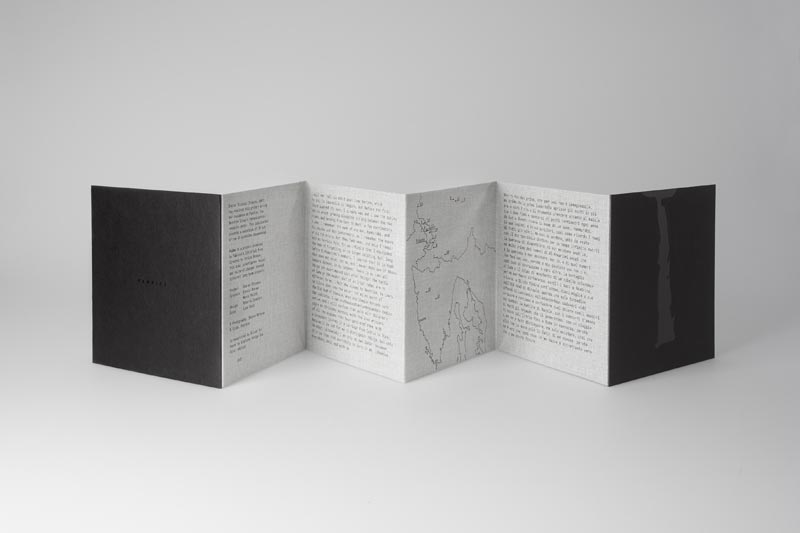

With Roberta Donatini, Mario Peliti and Enrico Bossan, whom I worked with in the project’s book development, we decided that a photographic map was the best medium to tell this story as such a map of the foibe doesn’t exist. I wanted to recreate the atmosphere of ancient military maps used before World War II, made with canvas and paper. Canvas was used overleaf the printed map because of its resistance when taken on the field, so I also used canvas for my map. Inside are the definitions of foiba and foibe in all the languages of the victims. I then included the foiba’s exact location and depth. This was important for me to allow readers to visualise how many bodies the holes could contain, which is impossible to tell from the photographs. The grid with the 18 pictures reveals itself when the map is open, and the reverse side consists in the more poetic part – as opposed to the dictionary-like introduction – with an essay by the Italian writer Luca Rossi in which he turns into a foiba, narrating everything he witnessed in his life.

Lastly, who would you dedicate this body of work to?

To the families of the victims, obviously. Then to my cousin, Michele Potleca, a very talented geologist who helped me in my research, and his brother, Alain Potleca, who passed away years ago.

Interview by Marina Vitaglione, Journalist and Photo Researcher at Fabrica.

Foibe is available on the Fabrica online store and is exhibited in Galleria Del Cembalo in Rome until January 2017.

Publisher: Fabrica

Year: 2016

Format: 18×18 cm

Graphic design: Roberta Donatini

Curators: Mario Peliti, Enrico Bossan

Languages: Italian, Slovenian, Croatian, English, German

First limited edition, 100 copies

Screen printed on canvas

Fabrica is a communication research centre. It is based in Treviso, Italy, and is an integral part of the Benetton Group. Established in 1994 from a vision of Luciano Benetton, Fabrica offers young people from around the world a one-year scholarship, accommodation and a round-trip ticket to Italy, enabling a highly diverse group of researchers. The range of disciplines is equally diverse, including design, visual communication, photography, interaction, video, music and journalism. Fabrica is based in a campus centred on a 17th-century villa, restored and significantly augmented by renowned Japanese architect Tadao Ando.