FEATURED STORY

Down by the Hudson

BY CALEB STEIN

Back in 2018, one of Caleb Stein’s images was selected by Martin Parr in our Open Call competition – an image we described as direct, austere and honest, and that it transpires came from his long-term series Down by the Hudson.

It’s a body of work he has been slowly and lovingly crafting for almost a decade, an ode to the small upstate New York town of Poughskeepie in his adopted home of the US. And central to it is the town’s watering hole, where people of all ages, races and status come to relax in the warm summer months.

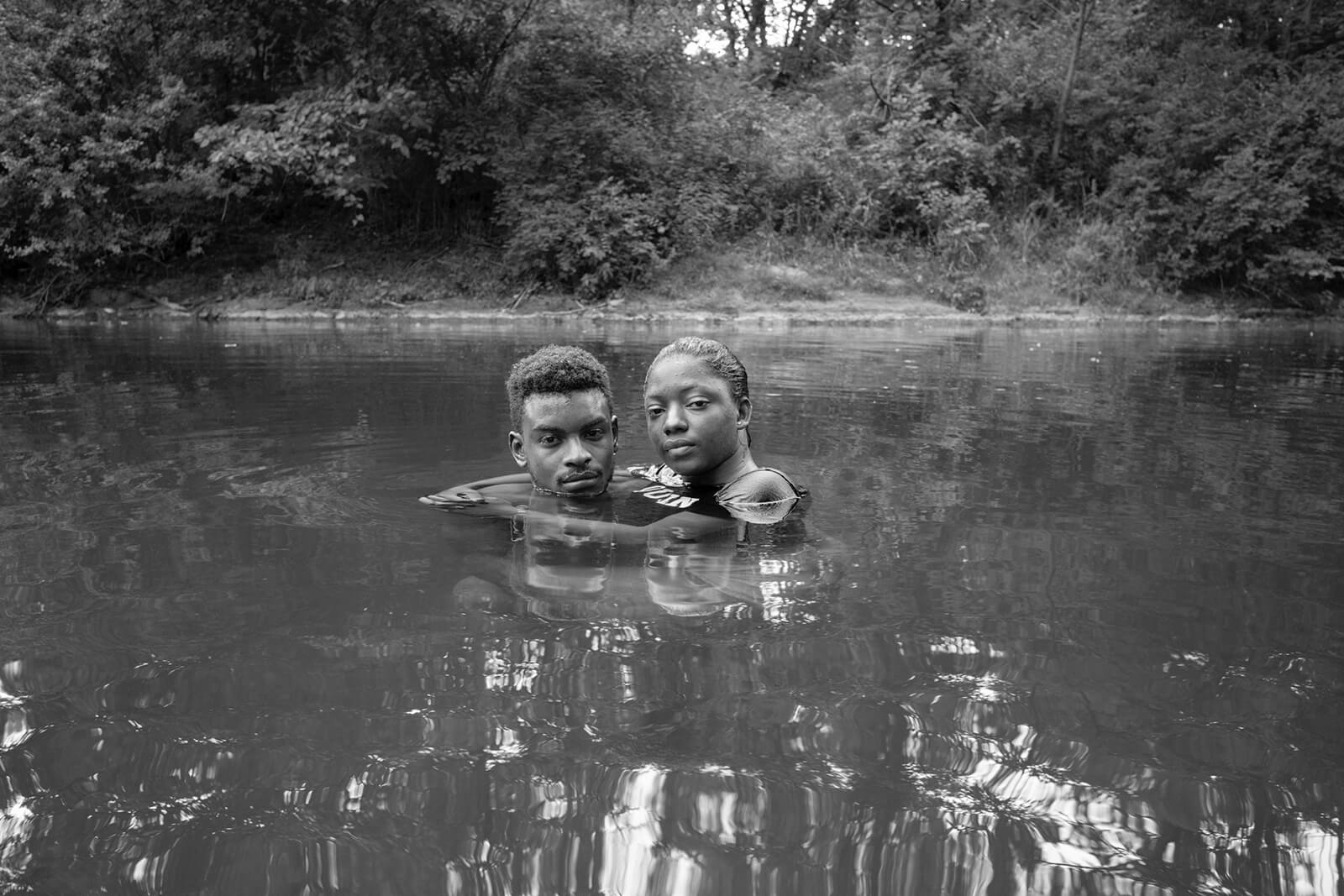

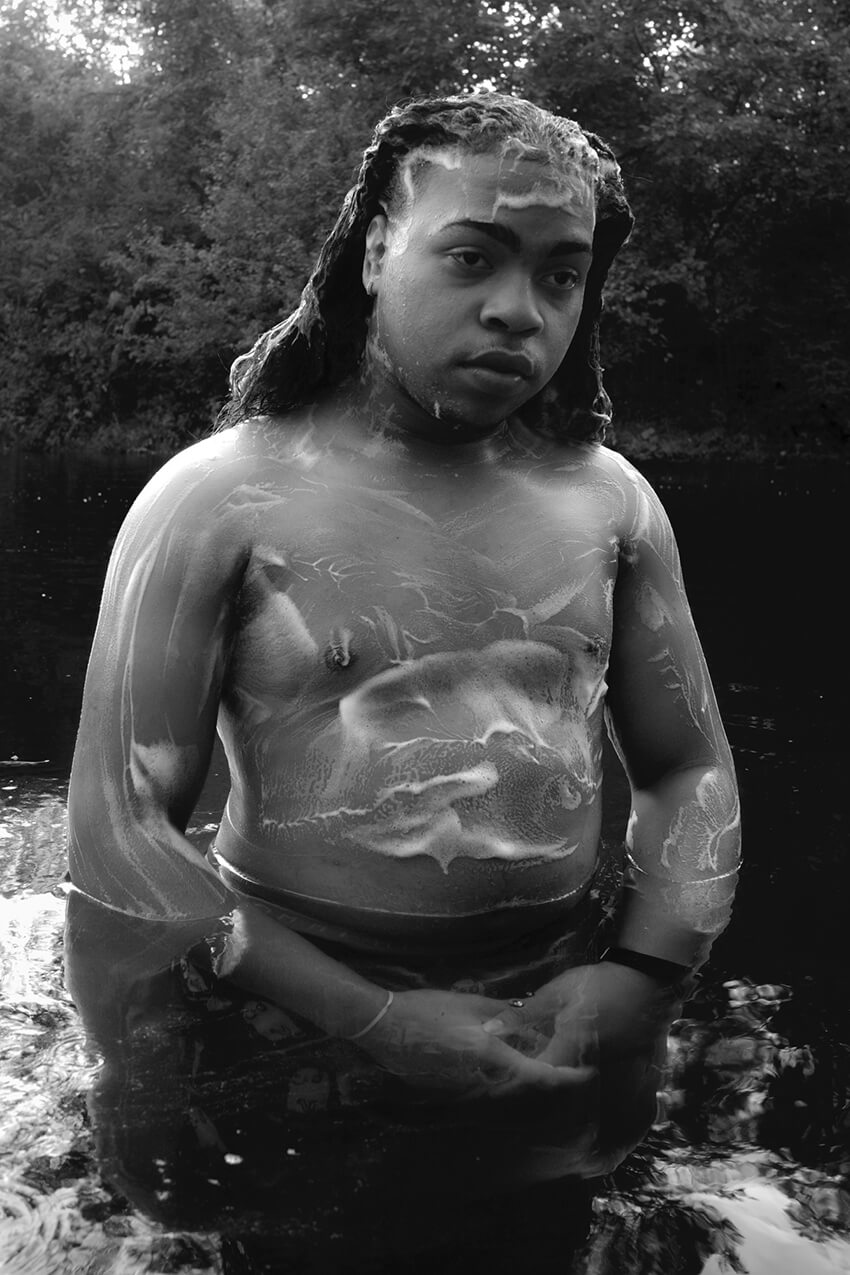

In a world that feels increasingly complex, anxious, busy and partisan, the watering hole at Poughkeepsie seems like an antithesis to that – a mini-Eden of tranquillity, play and community – “a reprieve of sorts from the tensions of our era” as Caleb puts it. Shot in black & white, and with few clues to the present day, it seems to exist in its own time and space, and Caleb introduces us to the characters who frequent it through a series of intimate portraits.

Recently exhibiting the series in Los Angeles, he’s perhaps – non-committal by his own admission – drawn a line under the project, and so it felt like a good time to ask Caleb some questions about it.

SANJAY & SHERIKA

BRAILY

EMMA

MICHAEL

SUMMER

SHAMUS EMBRYO POSE

What first took you out to Poughkeepsie?

I lived in Poughkeepsie on and off for several years. I went there to study at Vassar College. After I graduated I moved to Main Street, took on a job as a waiter, and later as a studio assistant to a photographer who lives in the Hudson Valley. After I moved away I came back during the summers to continue photographing and to see my friends.

What was your first experience of the town’s watering hold, and at what point did you realise it would become a project for you?

The first time I went to the watering hole was nearly ten years ago. Andrea Orejarena, my partner who I often work with as an artist duo, introduced me to it early on in our time at Vassar. Growing up I was obsessed with water and was a long-distance competitive swimmer, so going to this watering hole during the summers became a regular part of my life. It wasn’t until 2016 that I started to photograph at the watering hole. I had been photographing in the town of Poughkeepsie and I felt that I had hit a wall with that work. Andrea, who is a major mentor figure for me, suggested that I focus on the watering hole instead. That’s when things opened up. It’s funny how sometimes it can take years for work to fall into place. With time I’ve come to accept that this process is an integral aspect of any creative work.

And tell us about that working process… how did you go about documenting the community frequenting this spot? And what did they make of you?

My photographs are the natural product of a relationship – some span several years, others form over the course of an afternoon at the watering hole. In each case the process is an act of vulnerability and exchange on both sides.

I don’t photograph without consent – I don’t think photography is important enough to make anyone feel uncomfortable. I’m not drawn to photographs that act as one-line-jokes. I’m interested in work that comes from a place of love. I approach people I’m drawn to and ask them if I can make a photograph as a way of celebrating them and engaging with them. My practice is deeply informed by Martiniquan philosopher Eduard Glissant who once said “I can change, through exchange”.

My work is also an act of placemaking, it’s a way of understanding how I fit into a town and a country that are my adopted homes. I share all of what I’ve said above with each person I photograph – I let them in on the process, and I share the work with them as I’m making it and I share other examples of my work to provide them with a frame of reference. This transparency is a crucial component of what makes these photographs possible. With time, many of the people I photographed became friends, and in many cases the act of photographing became an opening for a larger conversation about our lives, our country, and how this watering hole feels with all of that in mind. I also have become the unofficial photographer of this watering hole, and I am often called on to photograph people jumping off the rope swing or with their friends, partners and families.

And I understand the work was near a decade, on and off, in the making. What did this amount of time afford you, and would you now call the series complete?

At the beginning, photographing in Poughkeepsie was a way for me to investigate how inherited mythologies of small town American life matched up with what I saw as I went on my long daily walks. As the years passed I realized that I was not only making photographs of a place, but photographs that reflected how I had changed in that space. It’s a strange, wonderful thing — to start photographing a place at 19 and to still be photographing it at 28. As I spent more time in the town, particularly at the watering hole, I felt a responsibility to show the space with care and tenderness, maybe especially because this is where I met the love of my life.

I feel that my work at the watering hole may be done, but only time will tell. A solo exhibition of twenty six works from ‘Down by the Hudson’ is currently on view at ROSEGALLERY in LA. It’s often felt like I’ve needed to keep all the threads together internally for the whole thing to make some sort of sense to me. Now those threads are on the wall in a way and a weight has been lifted, in large part thanks to key support from Rose Shoshana who is a wise, clear-eyed, fairy godmother to many photographers. I’m also beginning to translate this work into book form; I love how a book can become an exhibition or a museum without walls, and I’ve always thought about this work with the book form as its final form.

MEN & HUSKIE

LEO, LIZA, LILLY & WILLA

BODE & OWEN WRESTLING

And there’s a real tenderness and honesty to the portraits. Tell us about one or two of your subjects…

Thank you, that’s kind of you to say. One of the aspects of photographing people that fascinates me is that sometimes people view me as a therapist of sorts. People have shared so much with me over the years because they feel that I am open. It’s a responsibility and a major honor.

In 2018, I was photographing two young women – Emily & Belinda. As I was photographing with them they told me that they had been in a major car crash when they were children. Both of them had reconstructive surgery on their spines and for many years they had struggled to move. They told me that this was the first time they had been swimming since their accident. We talked about the healing power of water, about its immense spiritual, emotional, and physical capacity to regenerate.

Some of the people I’ve photographed have become wonderful friends. I first met Nate in 2015 with his family, and I photographed him as he taught his son, Nathan, how to float. He’s such a loving father and I was drawn to that and how it was expressed in this space. This last summer, five years later, we spent almost every day together, swimming, hanging out, playing volleyball in the water. One day Nate invited Andrea and I to join him on his canoe. We paddled from ten miles upstream until we reached our spot. I was struck by how in that ten-mile stretch there was nowhere other than our watering hole that could accommodate so many people because everywhere else the forest extends right up to the bank of the creek. It opens up at the watering hole; there’s a natural architecture that lends itself to community gathering. It’s a place that brings people together.

Your artist statement touches on contemporary themes of voter divide and post-industrial decline, but there’s a timelessness in the subject matter and your depiction of it – skin and water, with very few temporal clues, and depicted in black & white. Was this a deliberate stylistic choice?

I’m drawn to the relationship of photography to memory. I like the timelessness of black and white. I like how a black and white photograph can look like it was made a hundred years ago or a hundred years from now. For example, when I look at some of August Sanders’ photographs I feel like they look like they could have been made tomorrow.

I think black and white can be related to the future because it’s so deeply engrained in how we grapple with memory and the past that it will continue to be used as a way of grappling with that and encoding moments into a sort of timelessness. And that’s an approach that people are going to continue to use. Black and white photography is an effective language for grappling with mythology and memory and that’s not going to go away.

And finally, what is it you hope the viewer takes from your work?

I hope that the viewer feels a sense of peace and hope when looking at this work and that they feel free to engage with it on their own terms. I think we all need that now.

ERIN, ROBERT & FRIEND

EMILY & BELINDA

MATTHEW & ODEN

MICHAEL & HIS FRIEND EMBRACING

STATUE IN WATER

NICK