INTERVIEW

A Photographic Identity

WITH ALAIN SCHROEDER

AN INTERVIEW WITH ALAIN SCHROEDER

“I am convinced that my background leads me to choose a certain point of view, association of objects and color, and framing. You cannot escape your identity.”

Alain Schroeder won 1st Prize in our recent Street Life competition with an image judge Eric Bouvet praised for its “near perfect composition”.

Alain had been selected in our shortlists before, but with work of a more documentary or photojournalistic style. And so keen to learn more about his photography – what work he makes, where the passion began, and how several decades of experience informs his approach – we put some questions to him…

Dear Alain, congratulations on winning our Street Life competition. What did you make of the judges’ comments?

Eric said “I love this image because it resembles such a natural moment in the street… Here there are so many people in the frame, our eyes dart around everywhere absorbing them all and I love that. And of course the composition is near perfect. Bravo!” I do not consider myself as a street photographer so I am very pleased with this comment.

Can you tell us a little more about the image itself and the circumstances behind it?

At the time of the picture, a few years ago, I was walking around New York with my camera all the time. I was trying street photography. I have a certain way of approaching photography for a series, but street photography is totally different as it requires putting everything in one frame. In fact it is a good exercise. Like an athlete, in order to get better you have to train. But here, you train your brain.

This mural was in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan. There were many cars parked in front, so I chose the best place with reflections everywhere and waited for people to enter the frame.

I don’t think you’d describe yourself as a street photographer exactly. How would you describe your style or interest if you had to?

I like to tell stories in a personal, visual way. I try to be impartial in the sense that I don’t want to misguide the audience about what I saw, but I always try to do it in a more personal way, by the sense of framing, the use of color or black and white,.. In general, I am not a single shot photographer. I think in series. Editing is key. You can tell one story or another by where you place the accent. Both have to be true. I’m most interested in the in-depth reporting of stories relating to people and their environment. Various cultures, modes of living, rituals and customs fascinate me. I strive to tell a story in 10-15 pictures capturing the essence of an instant with a sense of light and framing.

Growing up in Belgium, I spent a lot of time at the library reading fine art books and studying surrealist painters. I was deeply impressed and loved them (especially Dali, Magritte, Chirico…). Nowadays, as a photojournalist and documentary photographer, there is often that one moment when I see a special arrangement of things that makes the reality look strange or different. It is visible in the story Kim City in North Korea, or in the 2 stories in Belgium; Les Marches and The Carnaval. Not only the framing, but the stories themselves evoke Surrealism, and I am attracted to that. Of course it is not always the case especially when you shoot human stories, but I am convinced that my background leads me to choose a certain point of view, association of objects and color, and framing. You cannot escape your identity.

ALAIN’S WINNING STREET LIFE IMAGE, MEATPACKING DISTRICT, NYC

FROM COAL SURVIVORS, DOCUMENTING THE SHRINKING MINING INDUSTRY IN UKRAINE

FROM COAL SURVIVORS, DOCUMENTING THE SHRINKING MINING INDUSTRY IN UKRAINE

FROM COAL SURVIVORS, DOCUMENTING THE SHRINKING MINING INDUSTRY IN UKRAINE

FROM COAL SURVIVORS, DOCUMENTING THE SHRINKING MINING INDUSTRY IN UKRAINE

What is it that drives you in your photographic practice?

Whatever the situation is, to find a way to be relevant. Let me give you an example.

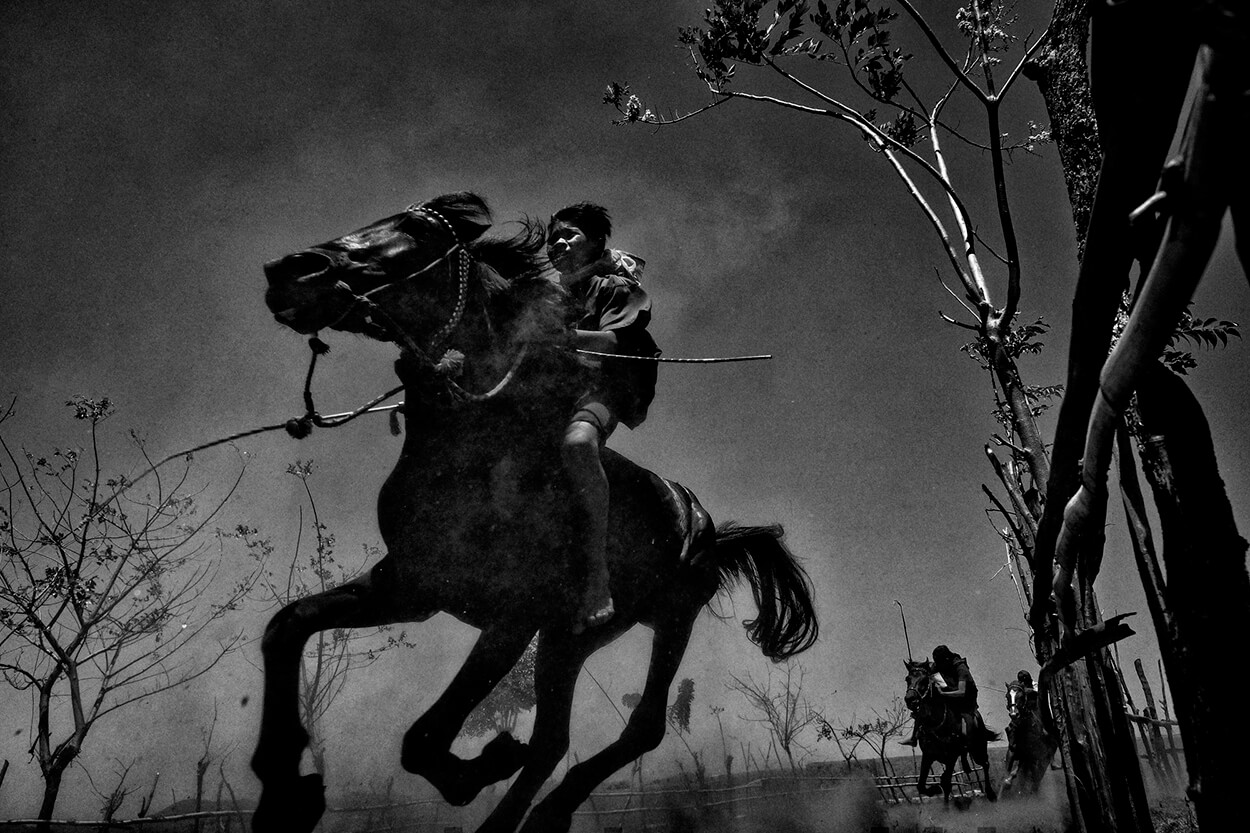

Light for the sake of light is not enough. Sometimes, the light is really bad and you have to work with it. My series Kid Jockeys was shot in Indonesia between 11am and 4pm. The sun was so high for most of the time that you could not see your shadow. With the jockeys wearing black face masks, I had no choice but to transform my series in B&W which ultimately added the drama that I did not have in color. You have to adapt your shooting to the situation and the light. When it is the right situation for color the shooting will be easy; same thing for black & white. But trying to shoot in B&W when it is a color situation or vice versa is difficult and not rewarding and you will know it very quickly.

In the Kushti series, it was important to connect the color with the meaning of the sport, connect the aesthetic of the red or yellow earth and walls to the spirit of the wrestlers. I have seen many Kushti pictures where you just see a color picture but the photographer forgot to explain the character of the wrestlers, or had no empathy with what was happening. For the Kushti shooting, every day I would focus for hours on a particular idea like the moment they come head to head, show respect to one another during massages and periods of rest, or put earth on themselves or their opponents. I shot and reshot these situations in different light, in different locations until I felt I had the right combination of light and content. Patience is key. In one location, I noticed that for a short period of time the sun would shine through a small window lighting just a square meter of the pit. I came back everyday to that place hoping something would happen and finally it did.

Sometimes technical improvements have an influence on your photographic language. For instance, today, many cameras are able to produce images in very low light with exceptional quality. This opens up an entire low light world which was not possible before. The Kushti and Brick Prison series would not have been possible without additional lighting in the analog era.

I believe you started out as a sports photographer. What was your first route into photography, and at what point did your horizons broaden to the travel / reportage work you focus on now?

When I was 15-16, a librarian gave me some photography books. One was the famous French magazine Photo and the first story I liked and remember was made by a Japanese photographer, Kishin Shinoyama. It was a very interesting magazine as it mixed all kinds of photography – fashion, documentary, travel, war, personal work – in one issue. After that I discovered another famous magazine called Zoom and all the classic photographers like Cartier-Bresson, Koudelka… I was hooked and switched immediately from fine art to photography classes. During my studies, with very little money I travelled to Afghanistan and caught the travel virus. It was the perfect combination of travel and photography but not easy to make a living at. Of course, you need a little bit of luck and it came by coincidence in the form of sports photography. I was asked to replace a tennis photographer who had fallen ill. At first I did not want to do it as I did not have the right (telephoto) lenses but the magazine had their own equipment so I could not refuse. As a long time tennis player, I knew immediately what to do and I captured the ball in almost all the pictures. The editor was impressed and hired me. That was the beginning of my professional career, and I haven’t stopped working since.

After 12 years of freelance shooting mainly sports events, I had the intuition that working alone was not the way to continue. Life as a freelance photographer can be precarious especially if you only have 1 or 2 big clients which was my case at the time. Losing one account could lead to bankruptcy. In order to survive, it was necessary to create a structure that would be strong enough to withstand client turnover.

In 1989, with two other photographers, I established Reporters Photo Agency, and within a few years it grew from 3 to 25 people. I have done all types of photography over the last 30 years, plus I had to learn all the administrative and financial aspects of running a larger company which helped me tremendously.

Around 2000, business was getting harder due to the internet and the rise of digital cameras (both great things). Competition became tougher and more diverse, not only from other agencies, but almost anybody could sell or try to sell pictures. Prices dropped. This revolution affected magazines and newspapers as well and the money suddenly disappeared. Magazines no longer offered assignments nor guarantees and we were forced to explore other sources of revenue like corporate communications and video.

FROM THE SERIES KUSHTI, DOCUMENTING TRADITIONAL INDIAN WRESTLING IN AKHARA

FROM THE SERIES KUSHTI, DOCUMENTING TRADITIONAL INDIAN WRESTLING IN AKHARA

FROM THE SERIES KUSHTI, DOCUMENTING TRADITIONAL INDIAN WRESTLING IN AKHARA

FROM THE SERIES KUSHTI, DOCUMENTING TRADITIONAL INDIAN WRESTLING IN AKHARA

Are there particular skills or processes you developed working as a sports photographer that have had a particular influence on your more recent work?

Yes from that period I kept a few things; I am fast and I can handle the pressure in a lot of situations – pressure of the event, pressure of loud sounds or of a lot of people, pressure of something that will not happen twice, and fast focusing, though you don’t need that skill anymore with modern cameras.

As someone who has shot stories all over the world – from child jockeys in Indonesia, to orangutan conservation in Indonesia, to grandma divers in South Korea and many, many more – how do you find your locations and stories?

When I find something interesting I file it on my computer. Years later, when I’m in a particular country, I eventually have something to check or research that can become a story.

And what would be your dream destination, or subject matter to shoot?

I have no dream destination and no dream subject. I take things one day at a time.

You’ve shot photography for over four decades. What’s the key to such longevity, both a personal love of what you do, and in industry terms?

You cannot be in this industry if you don’t love what you do. I was a professional photographer for 45 years and now I am technically retired. I was responsible for an agency for over 20 years and during that period I was working for others making sure salaries were paid and handling many administrative tasks. In 2012, I sold my shares in order to travel the world and shoot personal projects focusing on social issues and human interest stories. I have won many awards since, notably, 1st prize at World Press Photo 2018 in the category Sports Stories with Kid Jockeys and in 2020 two World Press Photo awards for Saving Orangutans in Nature Stories and Nature Single. I have also won POYI 4 times, Istanbul Photo Awards 5 times, Siena 9 times… It has been extremely gratifying.

FROM THE SERIES KID JOCKEYS, DOCUMENTING HORSE RACING ON SUMBAWA ISLAND, INDONESIA

FROM THE SERIES KID JOCKEYS, DOCUMENTING HORSE RACING ON SUMBAWA ISLAND, INDONESIA

FROM THE SERIES KID JOCKEYS, DOCUMENTING HORSE RACING ON SUMBAWA ISLAND, INDONESIA

FROM THE SERIES KID JOCKEYS, DOCUMENTING HORSE RACING ON SUMBAWA ISLAND, INDONESIA

What’s the best piece of advice you’d pass on to your younger self if you could?

Let’s start with the advice I did not get when I was a young photographer.

I started to study photography in 1971. I had very good technical B&W teachers (of course analog at the time, which has helped me a lot throughout my career) but unfortunately nobody in the photojournalism field. I had to learn by myself when I started as a professional sports photographer. To give you an example, over the summer holidays in 1974, I hitchhiked from Belgium to Afghanistan crossing Europe, Turkey, and Iran for my final school project. Along the way I documented people in all those countries but I “forgot” to make a story about the people in their twenties called hippies, traveling the world. At the time I did not understand the journalistic value of that particular story because I had no photojournalism background, only an aesthetic approach to photography.

In terms of advice, I have to share an interesting experience I had when I was a sports photographer. I was invited for many years to participate in the making of the book «Roland Garros seen by the 20 best tennis photographers in the world» managed by Yann Arthus-Bertrand, the famous French filmmaker and photographer. In a restricted area of Roland Garros, the idea was that every day 20 photographers had to bring back a few good pictures that were immediately displayed on a wall. Yann would select the best ones for the book. Some days you did not even make the wall selection! But every day your colleagues made good pictures sometimes when you had not seen anything special. They might have found a new location, a different perspective or taken photos at night after the matches, etc. What does it mean? The pictures are there, they exist. You have to ask yourself, how can I make a good picture and where is the best place, then find the spot and make it happen (I mean wait for it to happen not provoke it). So I know that the pictures “exist” in a sense, and if I don’t get them myself another photographer in the same place will find the way to reveal them. There is always a good picture to be taken, you just have to work hard to get it. That idea never leaves me.

FROM THE SERIES UPPER EAST SIDE STORY, DOCUMENTING NEW YORK CITY’S MOST AFFLUENT NEIGHBOURHOOD

FROM THE SERIES UPPER EAST SIDE STORY, DOCUMENTING NEW YORK CITY’S MOST AFFLUENT NEIGHBOURHOOD

FROM THE SERIES UPPER EAST SIDE STORY, DOCUMENTING NEW YORK CITY’S MOST AFFLUENT NEIGHBOURHOOD

FROM THE SERIES UPPER EAST SIDE STORY, DOCUMENTING NEW YORK CITY’S MOST AFFLUENT NEIGHBOURHOOD

All images © Alain Schroeder

Follow him on Instagram: @alainschroeder and see more at www.alainschroeder.myportfolio.com