FEATURED STORY

Hometown Histories

WITH KYLER ZELENY

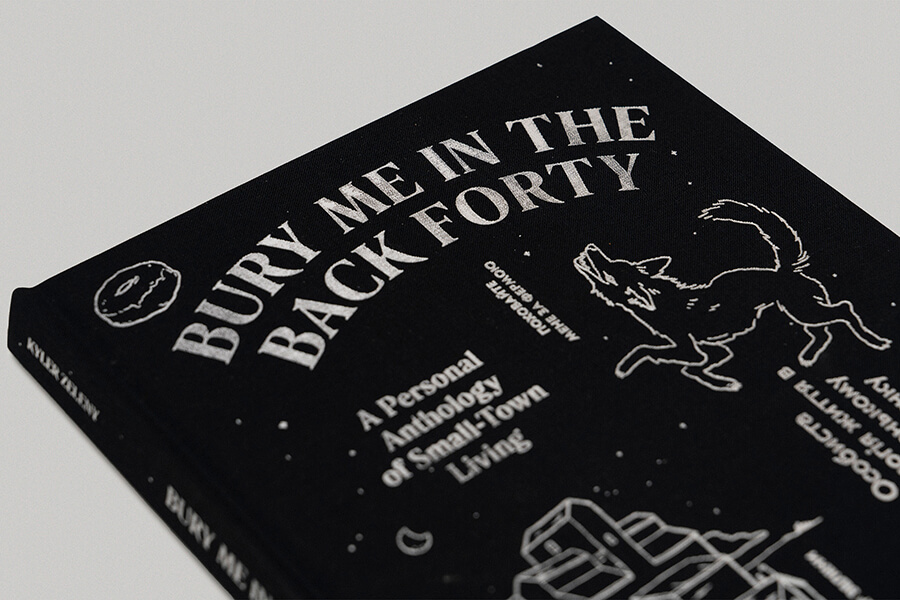

Bury Me in the Back Forty

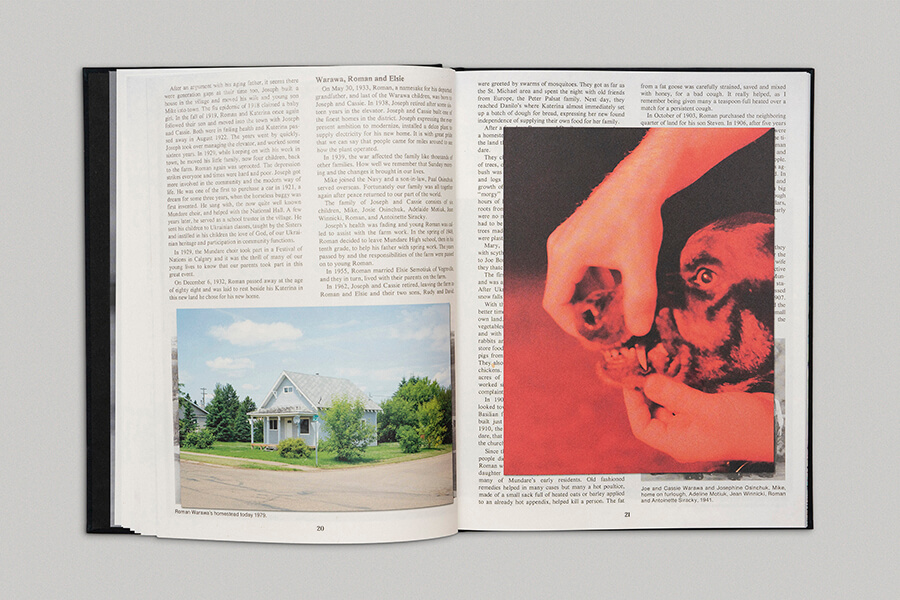

Canadian photographer and researcher Kyler Zeleny has been photographing his home for over a decade, a small town of just over 900 inhabitants with deep Ukrainian roots in the Canadian prairies. Fascinated by the idea of how these rural communities have evolved – many might say ‘declined’ but as ever the reality is far more multi-faceted – he has dedicated his efforts to create a beautiful community album, a record of the joys and tragedies, hardships and humor, deviance and conformity, and the quiet stoicism that is both unique to the town of Mundare and universal.

Following Out West (2014) and Crown Ditch and the Prairie Castle (2020), his new book Bury Me in the Back Forty is the final chapter in a prairie trilogy that is both an ode to small-town living and to the act of documentation – to the importance of archiving and preserving stories that together describe a place forever in a state of impermanence. Kyler puts it far more simply himself: “The book is about funeral donuts, bush parties, and that gut feeling you get when you return home after a long stint away.”

We asked Kyler to tell us the story behind a few of the images in the book: “I wanted to share a few prairie elements that folks outside the region might not understand” he said. “Others may have their own versions of these elements, and I won’t argue that gravel roads and donuts are unique to the Canadian prairies, but the region does hold a special reverence for them. So, let’s talk about prairie castles, fresh funeral donuts, hay bales, tin machine shops and dusty gravel roads…”

Bury Me in the Back Forty is a pluralistic history of the community that embraces both official and unofficial accounts of events in the community’s past – one that contains not only the roses but also the numerous thorns attached to each stem. It encapsulates the collective virtues and vices found at the heart of any complex place on the verge of disappearing. More importantly, it is simply a story being recorded, recollected, and reconfigured. The result of which is the stoicism of place, a lived existence, which roars at times and suffers so quietly at others.

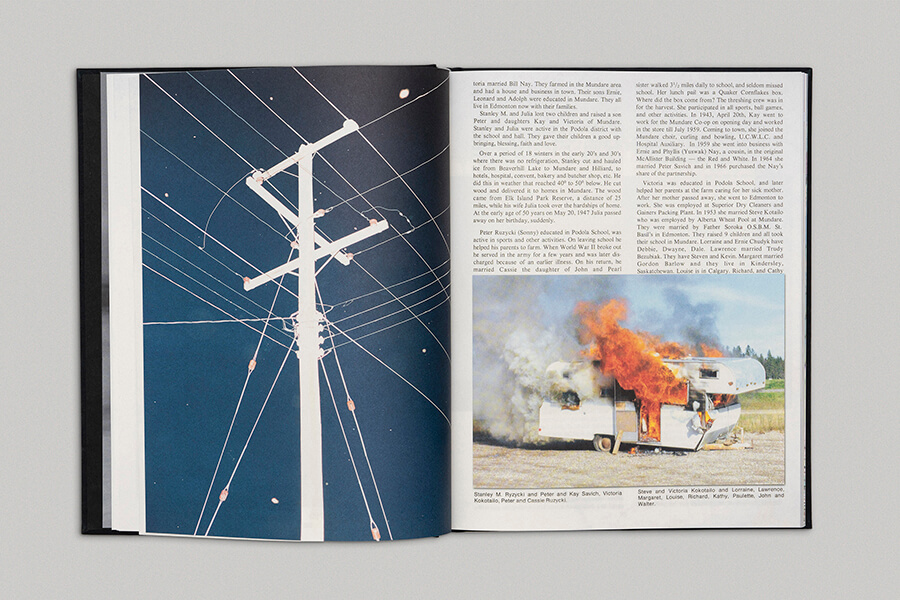

PRAIRIE CASTLES

The prairies often register as a landscape of nothingness, a wide and flat formation of grasses and genetically modified crops. A town sprinkled here. An old farmhouse there. Not much to write home about. With its relative featurelessness, tall structures like grain elevators become impressionable landmarks—small vertical thrusts that challenge the region’s defining horizontality.

The grain elevator is one most emblematic structure of settler culture in western Canada. In many farmer’s homes, you’ll find paintings of our landscapes dotted with grain elevators and at the dining table you’ll reach for ceramic shakers holding not grain but salt and pepper.

From the outside, these quiet towers stood as community emblems—places where farmers brought cash crops and gathered to discuss politics amongst the grain trucks. But from the inside, they are dormant bomb factories, holding hundreds of pounds of highly flammable grain dust packed into crevices at all levels. Posing a fire threat and no longer economically viable, these structures are now being shuttered and razed in the name of modernization, replaced by high-capacity terminals in more centralized areas.

At its peak, my hometown of Mundare, AB, boasted nine grain elevators. Today, none remain—the last one was demolished in 2013. This is a symbolic death for the community, only rivaled by the pulling of a town’s railway line—unpleasant forms of communal castration.

FUNERAL DONUTS

For decades the rural grocery chain CO-OP has made glazed donuts. A fluffy and moist inside protected by a coating of sugar glaze. Fresh was always best. These would often be paired with black coffee at the back of a dance hall or town meeting. The small reward we all looked forward to after sitting through whatever social event rallied the community.

These functions provided opportunities for unity while continuously redefining social expectations. The demands of the early prairie pioneer meant alienation from everyone but immediate family, making social events like dances, concerts, weddings, town meetings, and funerals all the more crucial. Sadly, the most frequent of these gatherings nowadays is the funeral, which has given rise to the renaming of a stapled dessert, the delicious and simple glazed ‘funeral donut’.

Now, whenever I come across one of these CO-OP donuts, the sugar punch I would get from them is replaced by thoughts of how they now represent not so much the idea of community but the slow death of it.

HAY BALES

Grow up on a farm and you know the fun of scaling bales and then racing your cousins across the tops of these golden prairie fixtures. It was fun but there were dangers, like a 1,500-pound bale becoming lodged resulting in you dropping twelve feet onto hard dirt, or worse being pinned by the bale. Farm deaths often occur when someone falls into a grain cart or a bin, suffocated by tightly packed grains, but bales are also no joke.

Once a sizeable formation of dried feed in the form of grass and chaff, the depot of hay bales at my grandparent’s farm have shrunk over the last decade. This is in stark contrast to when I was a child and the bales held a formidable footprint – many rows wide, thirty bales long, and three high. Enough to feed 150 head of cattle through an Alberta winter. Now what is left is a handful of bales used to feed the last remaining horse housed in the fenced pasture of the ‘old yard’. Surely, not enough bales to race across.

THE WORKSHOP

Every farmer has a workshop or machine shop. They are spaces to store tools, to tinker away on moody tractors, house prematurely born kittens, and of course a place to loosely curate local artefacts. Like most artefacts holding a folklore value, they’re found in the loose draws, in discard piles and buried under and upon years of dust. These are objects that take on meaning over time—sometimes it takes decades for them to secure their value.

I’ve seen these collections of objects and ideas in the machine shops of my father, my grandfathers, and other community members. They are eclectic, items that don’t have enough value to place in the house or the attached garage. Which might be why I find them so binding.

The curling trophy from 1988, the farmer standing next to his prize cow at a 4-H competition, the short neck bottles of Pilsner, the blue and orange coloured twine used as a nest by a Sparrow, the endless shotgun shells and cigarettes, the wheat that always seems to find its way into your shoes regardless of where you trek.

I wanted to create a prairie tapestry, a collection of items familiar to me but that are often passed over as meaningless, but which in the embrace of time hold importance to understanding the region.

GRAVEL ROADS

I’ve always appreciated gravel roads. The dime-sized rocks crunching beneath one’s feet. The sharp ‘tink’ sound of errant rocks hitting the wheel hubs as a vehicle spits them up, out, and around. The light coating of dust that finds its way into your cab, onto your clothes and into your mouth if you dare keep a window down.

Like paddling down a river, you flow with the gravel, do not try to oversteer the vehicle. Let it pull you left and right, It’ll keep you going straight, It is ok, you’re in its trusty current. Gravel roads are often empty but the danger is always an intersection, or a mule deer darting out from the wooded periphery. Gravel roads at night with thick bushes and blind corners are always dangerous, adding booze only adds to the wager, a practice less common today than in the past.

We drove a lot of gravel roads at night when we were young seeking abandoned farmhouses, schools and churches to entertain ourselves. We threw Molotov cocktails on gravel roads and searched out places to call our own. The gravel roads where these country structures once thrived are now empty, a lonely and dark landscape, giving one the sense of ownership by virtue of presence alone. It is so quiet you forget people call these places home.

All images and text © Kyler Zeleny

See more at www.kylerzeleny.com and follow him on Instagram: @kylerzeleny