INTERVIEW

An Outrageous Beauty

WITH DAVID BARD

An interview with David Bard

“I hope that one day we will appreciate honest things again, just beautiful for what they are.”

As drone photography becomes more ubiquitous, an aerial image isn’t engaging in and of itself, in the same way it may have been when overhead images were the reserve of those who could go to the expense of hiring a helicopter. It takes something a little more special to arouse our attention and imaginations.

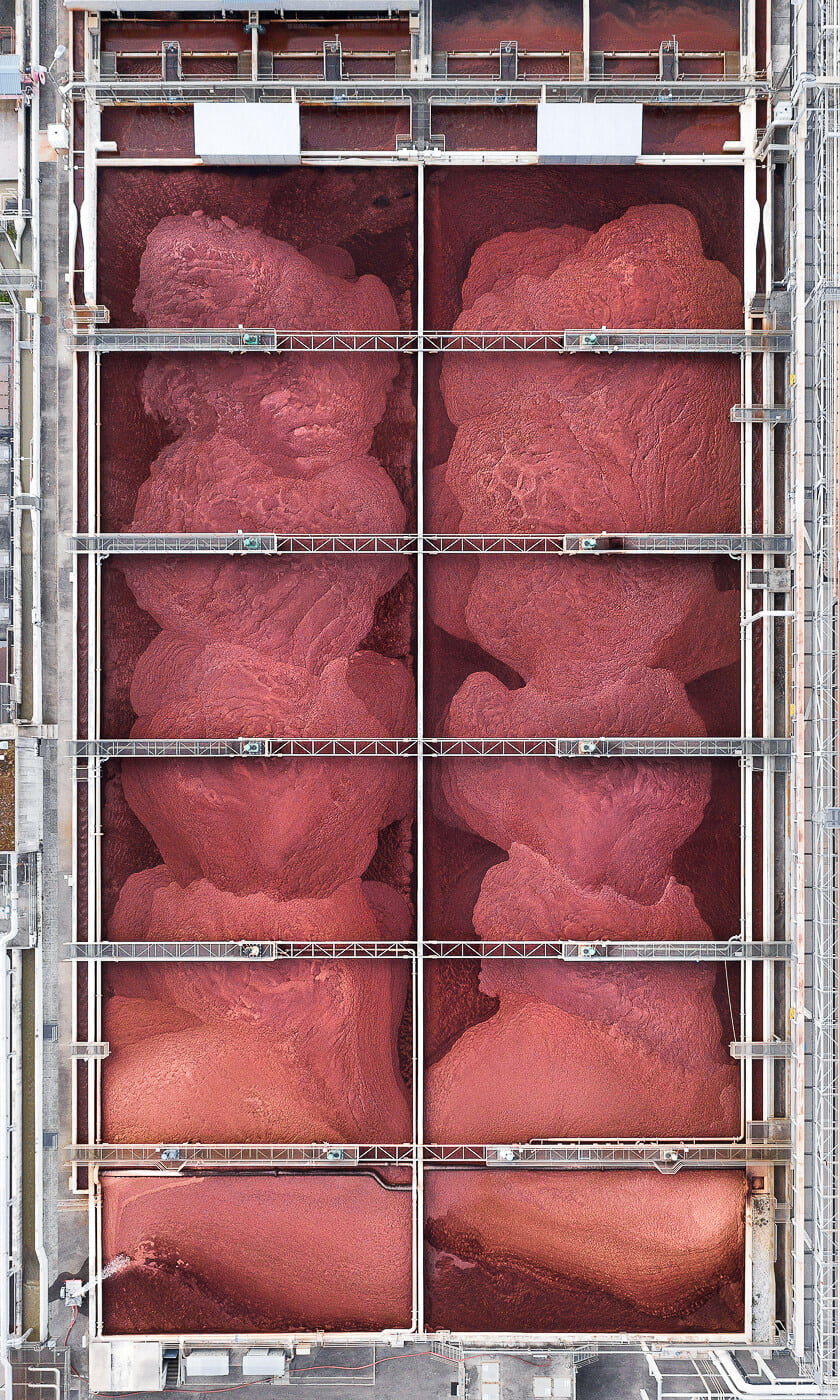

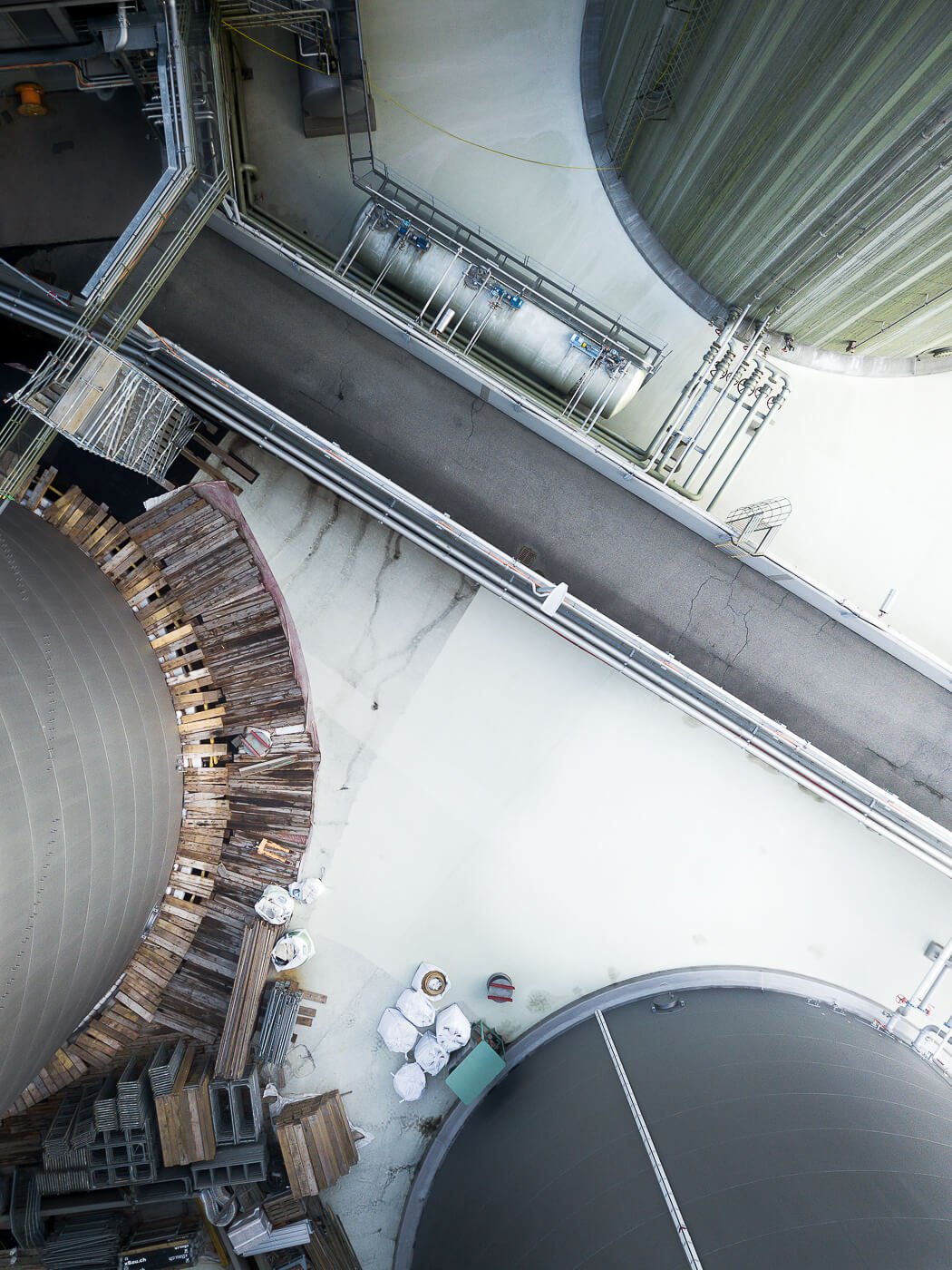

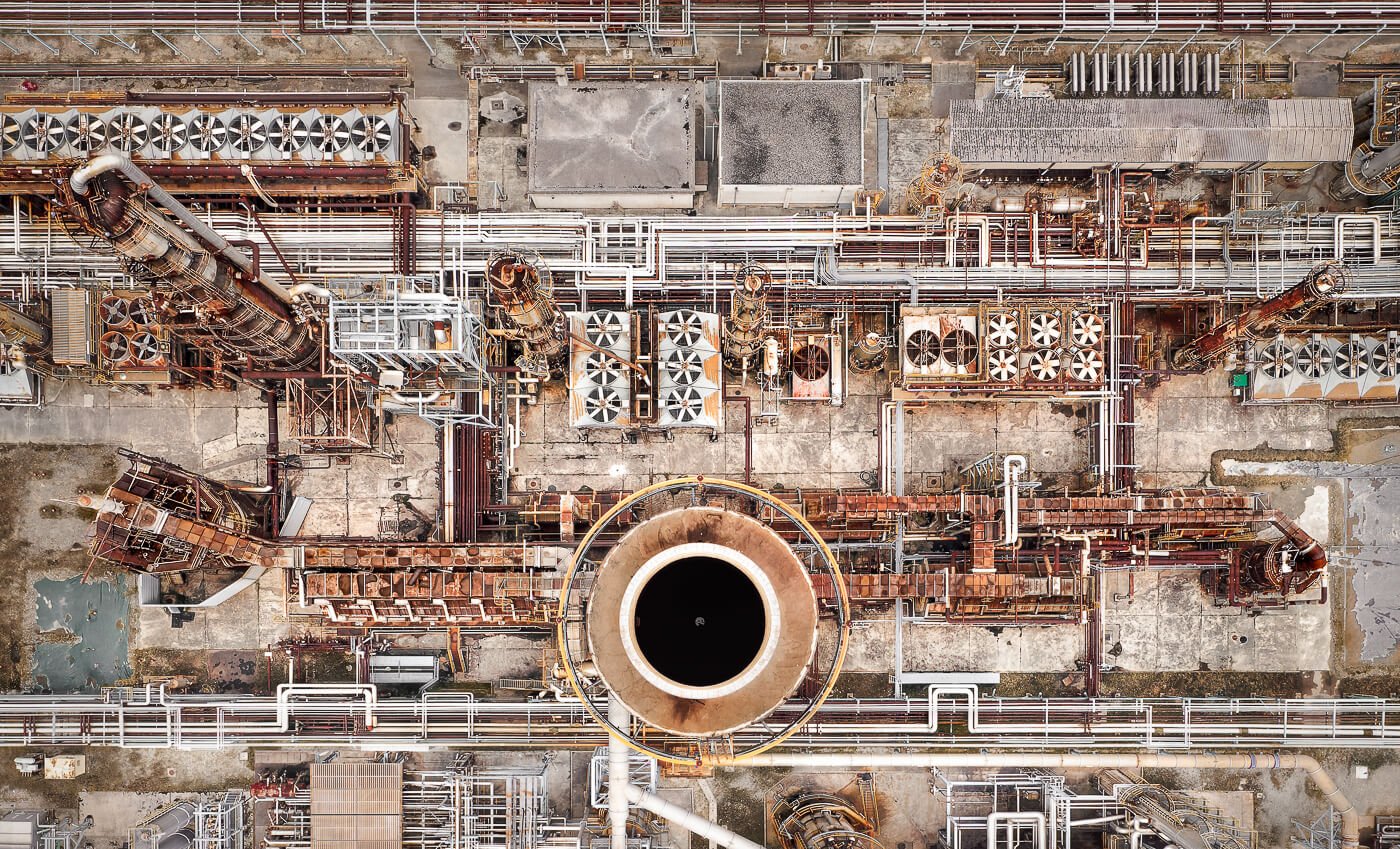

The work of David Bard, a young architect from Switzerland, does just that. Photographing desolate industrial landscapes with a meticulous eye for composition, his images highlight the terrifying immensity of these systems that support our modern world – the top-down perspective drawing out both their complexity and a strange aesthetic allure that on the one hand celebrates human ingenuity, and on the other creates an anxiety in how out-of-sync these creations are with the human scale, and the environmental damage they represent. It is this tension that makes for such compelling photography. “An outrageous beauty” as he puts it himself.

Keen to know more about his latest series “The Hidden Face”, and the ideas and techniques behind it, we put some questions to David. And it will come as no surprise that his responses – drawing on his design philosophy and architectural background – add a thought-provoking layer to the images themselves.

The Hidden Face – Artist Statement (excerpt)

“The industrial area was built for a sole purpose: to serve us. Both connected to and isolated from the environment in which we live, this landscape, greatly altered by the hand of man, hides behind its strict fences the aggression and power that characterizes it. Well protected from any intrusion, an industrial area thus hardly lets the ruthlessness of its buildings shine through. Marked by the rationalization and efficiency of its activity, an industrial area loses this coolness and sobriety as soon as the beginnings of a new use make themselves felt. Nature takes over its ancestral place again and begins to expand, new values are gained or space is solemnly made for the city once more. Within these barricades, spaces emerge that are expressions of raw crudeness, whether through the huge, oversized scale of the buildings or the almost inhuman vastness of the surroundings. At night these vast, endless expanses evoke a sublimity of absolute silence, but during the day they seem wild and terrifying. Whether they are fragile metal halls, monstrous steel machines or raw materials waiting to be transformed, they inspire us with their outrageous beauty. The astonishment of this fact, which at the same time evokes a feeling of fear but also great respect, makes us reflect on what we have always overlooked.”

To begin, tell us a little bit about your series – The Hidden Face – and what you hope to convey through it.

“The Hidden Face” represents constructed violence, the strongest expression of brutality. It shows landscapes that are strongly modified by the hand of Man that have the ambition, precisely through the bland and the ordinary, to produce things that are extremely surprising and extraordinary because they are precisely unsuspected. The bird’s eye view is very abstract. It distances us from preconceptions and arouses our curiosity because of this new possible overview. And no matter what the nature of the subject is, the splendor of an earnest and modest richness is just waiting to be brought to light under attentive eyes.

What first got you interested in this subject?

The strength and the desolation that can be shown by these places – both the huge, oversized scale of the buildings and the almost inhuman vastness of the surroundings. Whether they are fragile metal halls, monstrous steel machines or raw materials waiting to be transformed, they inspire us with their outrageous beauty. The astonishment of this fact, which at the same time evokes a feeling of fear but also of a great respect, makes us reflect on what we have always overlooked.

You find an awe in the immensity of our human creations, but also a strange beauty in these industrial aerialscapes – appealing patterns, textures and color palettes that emerge from what might be considered blights on the landscape. You must be conscious of that tension between beauty and ugliness, environmental blight and human creativity. How do you reflect on that?

Through the complexity of these installations, we discover the immediacy of their clustered arrangement, which can evoke wonder at a modest but striking honesty. This sincerity disappears nowadays in the idyll of this world dominated by sensationalism, which relentlessly fuels our desire, then represents a reduced decor of the complexity of our environment. We live surrounded by places that flaunt their brazenness without restraint and remind us of their limitations through so-called enticing artifice. Day after day, this race for the extraordinary leads us away from what really makes our cities, our villages and our landscapes: the insignificant.

From a practical perspective, can you tell us a little about how you made the images? How did you scout the locations, get the necessary approvals, find the exact compositions you wanted and so on?

The proposed images are a small selection of thousands taken. The locations are selected on cartographic sites, through satellite views. But the fragile existence of some places means that what is discovered in the first research is rarely still present when you go there.

A great rigor is put in the shooting, the images are taken in cloudy weather, without any sun and shade, unlike «traditional» photography. They are very precise in their framing and as an architect, I build a lot of my own images. I also invest a lot of time in post-production.

There is a lot of prejudice about drones that are often equated with espionage. It is true that it is difficult to know the pilot’s intentions if we didn’t see the,, and this often raises the question of flight approval and image rights. I have little scruples about flying over «vulgar» industrial storage. For more sensitive places, authorizations are requested but what is called the 5th facade in architecture (the roof) is as visible as the other 4 facades. I have great deal of respect for the places I flew over and I impose limits on myself.

Your day job is as an architect. Is photography a form of escapism, or would you say that it has an influence on your architectural practice? If so, in what ways? Do you appreciate the brutal, industrial architecture of these industrial structures, or do you think they could be radically rethought?

Architecture influences my photography and my photography influences my architecture. Photography has the advantage of offering a great freedom of expression compared to architecture. I have my own architectural office in Switzerland (Bard Yersin Architects) and we work in a context where we are extremely standardized in our projects, which often slows us down. I studied brutalist architecture a lot, especially brutalist ethics. I try to question our relationship to space, structure or materiality in order to reveal their intrinsic qualities, as immediate and brutal as they may seem. The industry is therefore a great source of inspiration in its constructive truth.

You’re currently exhibiting the work at the Musée du papier peint in the Château de Mézières, Switzerland. How did that come about?

I have the chance to exhibit and curate the exhibition “Primal: the interest of disinterest”. I contacted the museum to propose an exhibition whose theme would question our relationship to wealth. Through industry, rurality and urbanity, Joël Tettamanti, Jean-Marc Yersin and I tried to demonstrate the incredible fascination that can provoke the discovery of these forgotten territories. Defying prejudices by the immediacy of their subjects, our gaze can only be turned upside down…

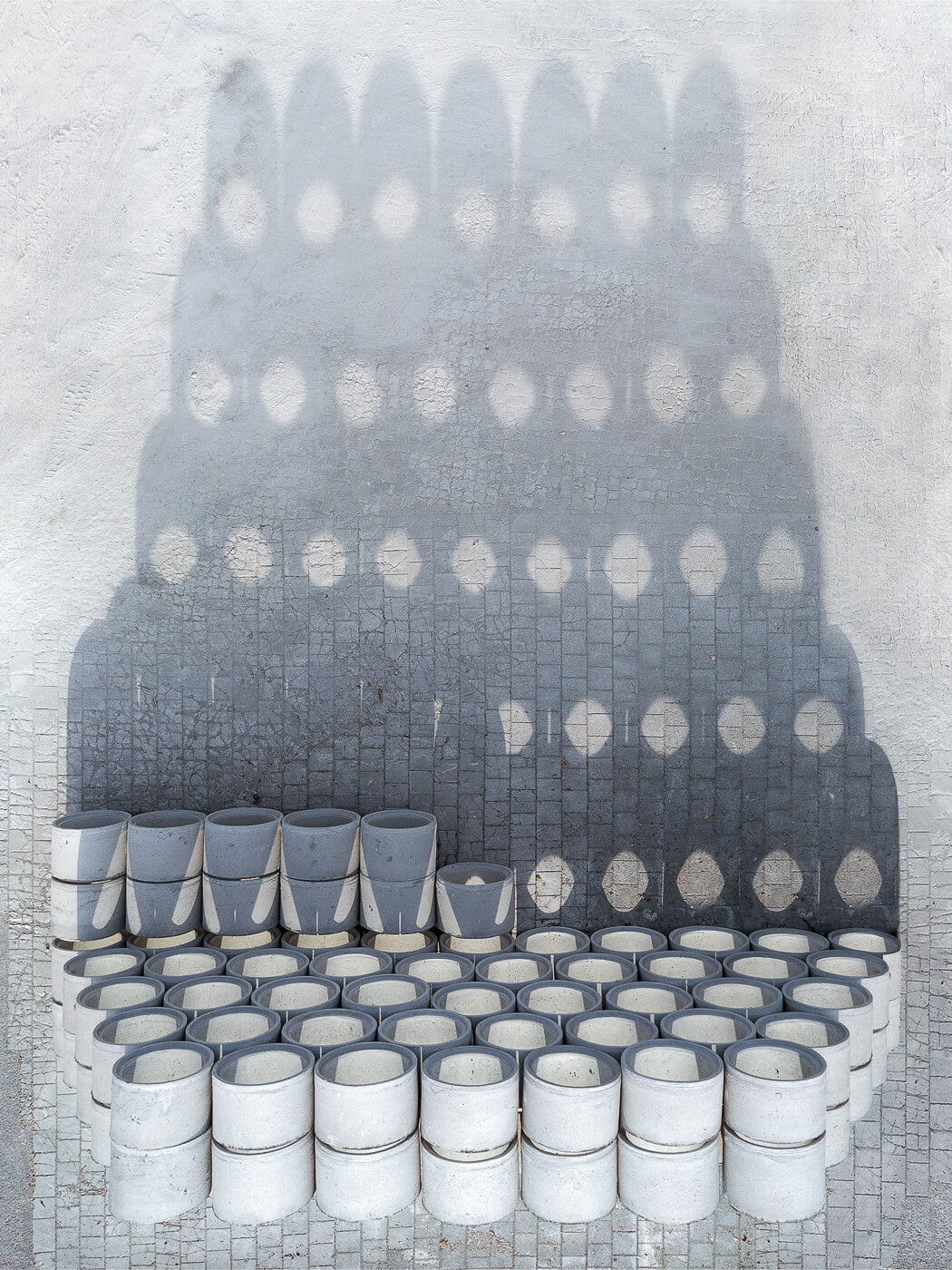

And I notice some very creative curation, for example displaying the works horizontally on what appear to be breezeblocks, giving that true aerial view. Tell us a little bit about the curatorial process.

The museum contains priceless wallpapers that cannot be touched or hidden. My images naturally took place on the ground, placed on insulating concrete bricks. They have no orientation, the visitor can freely turn around them. The perspectives evolve enormously according to the point of view. A dialogue is created between the wallpaper and the canvas on which my images are printed. Perhaps the experience of this exhibition will help us to remember that this castle, now a museum which we admire today in all its splendor, was abandoned for more than 30 years and considered one of these inept places.

And finally, you cite a Fabrizio De André quote: “Nothing can be born from diamonds, but flowers will grow from dung”. It beautifully captures the idea of finding aesthetic beauty in ugliness. Is this how you see it? And overall, does this project leave you feeling hopeful or fearful of man’s impact on our planet?

The building frenzy and the amount of fast construction that characterizes our environment today are quite questionable. Today’s modern man is constantly in search of quick gratification. The gaze of our commercial society is content with an illusory perfection that promises us instant satisfaction. I hope that one day we will appreciate honest things again, just beautiful for what they are.