INTERVIEW

The Essence of Childhood

WITH BOB HAFT

An interview with Bob Haft

“I gave [my students] the same advice that is often given to young jazz musicians: Imitate. Integrate. Innovate.”

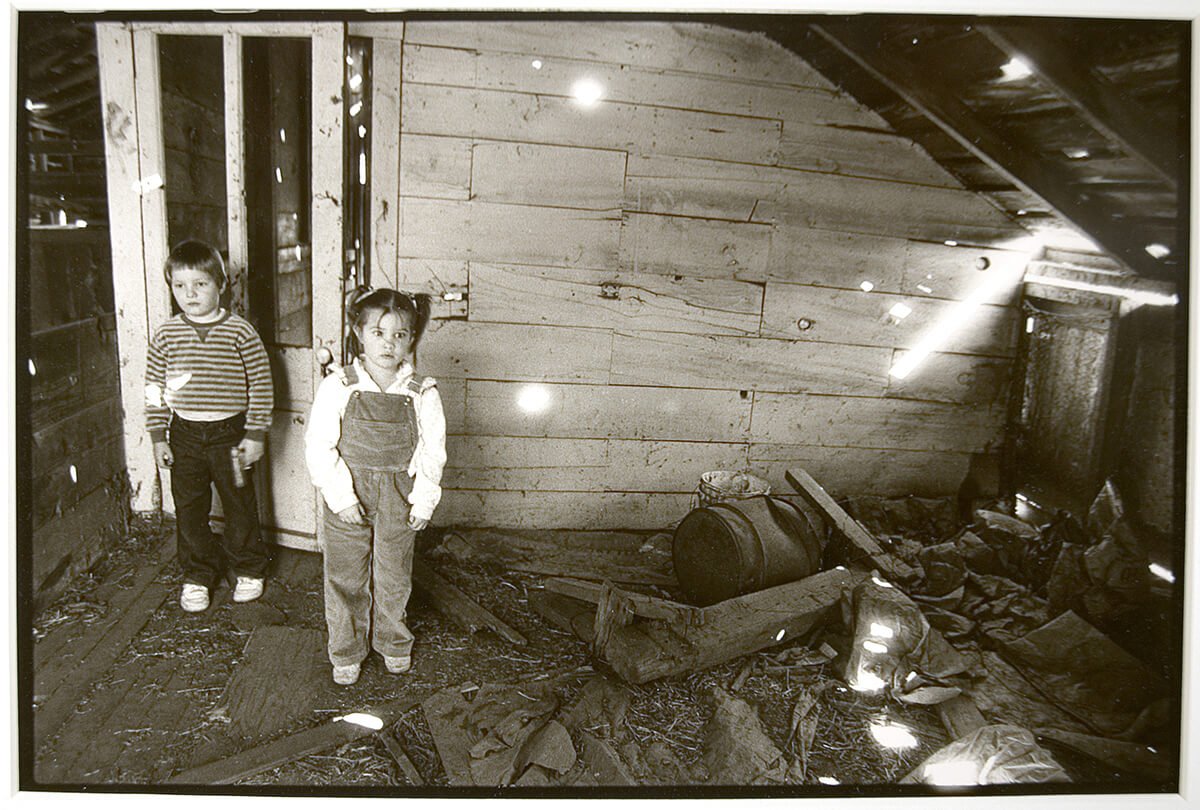

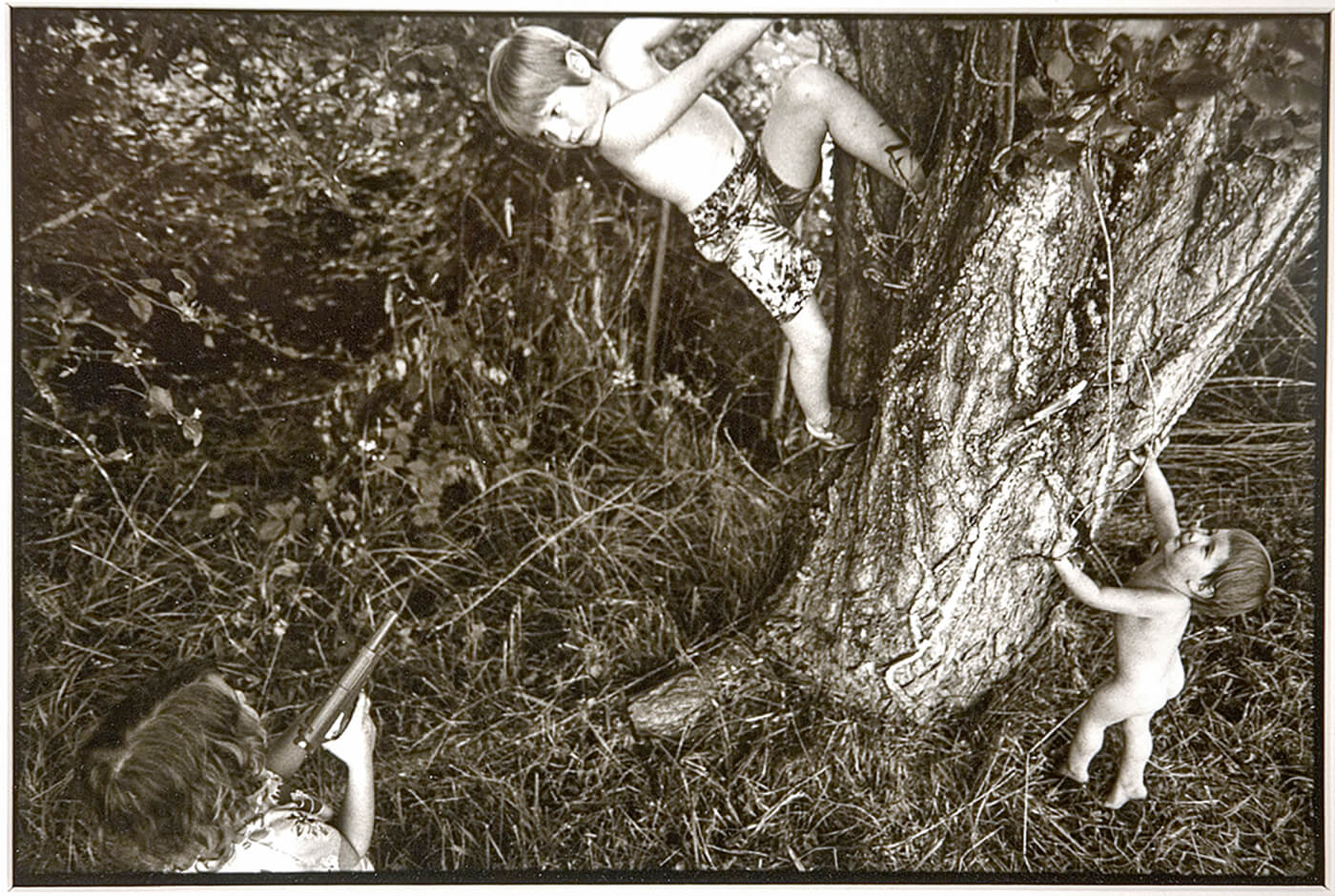

Bob Haft won our Youthhood competition with an unfiltered and uncontrived image that judge Hellen van Meene said “creates questions which are not easily answered”. Taken from a body of work spanning over 20 years, in which Bob documented his children and searches for moments of the marvelous in the commonplace, it uses a clever composition of candid subject matter to challenge our preconceptions around play, guardianship, and of course gun control.

Keen to know more, we put some questions to Bob, and his responses – covering his photographic practice, subject consent, the darker side of the internet, and his advice as a former professor of photography – are as interesting and thought-provoking as his images…

Hi Bob. Firstly, congratulations on winning our Youthhood competition. It’s a striking, cleverly composed image, and one that raises a lot of questions around the role weapons should or shouldn’t play in our lives, and particularly those of our children. Were you conscious of the provocative nature of the image? Do you take a stance on that subject?

I think Hellen hit the proverbial nail on the head with her comments about the photo. And, yes, I was conscious of the provocative nature of the image even as I took it. My wife and I actually had a “no gun” policy for our kids when they were growing up, but it was something that was almost impossible to enforce since the kids would use either their fingers or sticks as pretend guns; plus, guns are absolutely everywhere in American society, from sporting-goods stores to toy stores. In addition, we lived next door to my father-in-law who was a veteran of World War II, and who kept a BB gun around for shooting at the coyotes and other critters who occasionally attacked the geese and chickens that he kept. If you look closely at “The First Lesson” you’ll see that the hand in the foreground of the image is that of an adult; it’s my father-in-law’s hand and in the photo he’s teaching my then 5-year-old son how to shoot a BB gun. So eventually we just gave up in trying to enforce the “no gun” rule, and I have made a number of images where toy guns or other weapons are a seminal part of the photograph.

Many years ago I had an exhibition in Seattle of about 30 photos from the same series that “The First Lesson” was taken, and in three or four images in that exhibit there was a toy gun. There was also a blank book at the exhibition where people were invited to write their comments about the images. When the exhibition was over and I had a chance to read the comments that people had left, I was stunned by the large number of them that said something to the effect that these were horrible photos and I was a horrible person for letting my children play with guns! It was as if they missed out entirely on seeing the other images in the show that didn’t have that visual trigger (no pun intended). At the very end of the book of comments, however, there was an entry from a 13-year old girl who put things in an interesting perspective for me: she said, “Dear Mr. Haft, my brother and I played with guns when we were kids and we’re fine. Don’t listen to what other folks have written. I like your photos!”

So, over the years I’ve come to the conclusion that a lot of people who are scandalized or upset by what they see in an image like “The First Lesson” are often those who have neither children nor World War II veteran father-in-laws.

I understand that the image is from a 20 year + project through which you’ve documented your children. Hellen put it well in her judge’s analysis when she said “a good photo should be interesting and appealing, and not only for the parent of the child who is in the picture. It’s important to try to avoid “easy cuteness” – any successful image says something more universal to a broader audience”. It’s certainly something you get right in your images. Does that statement resonate with you? How do you navigate that idea in your own work?

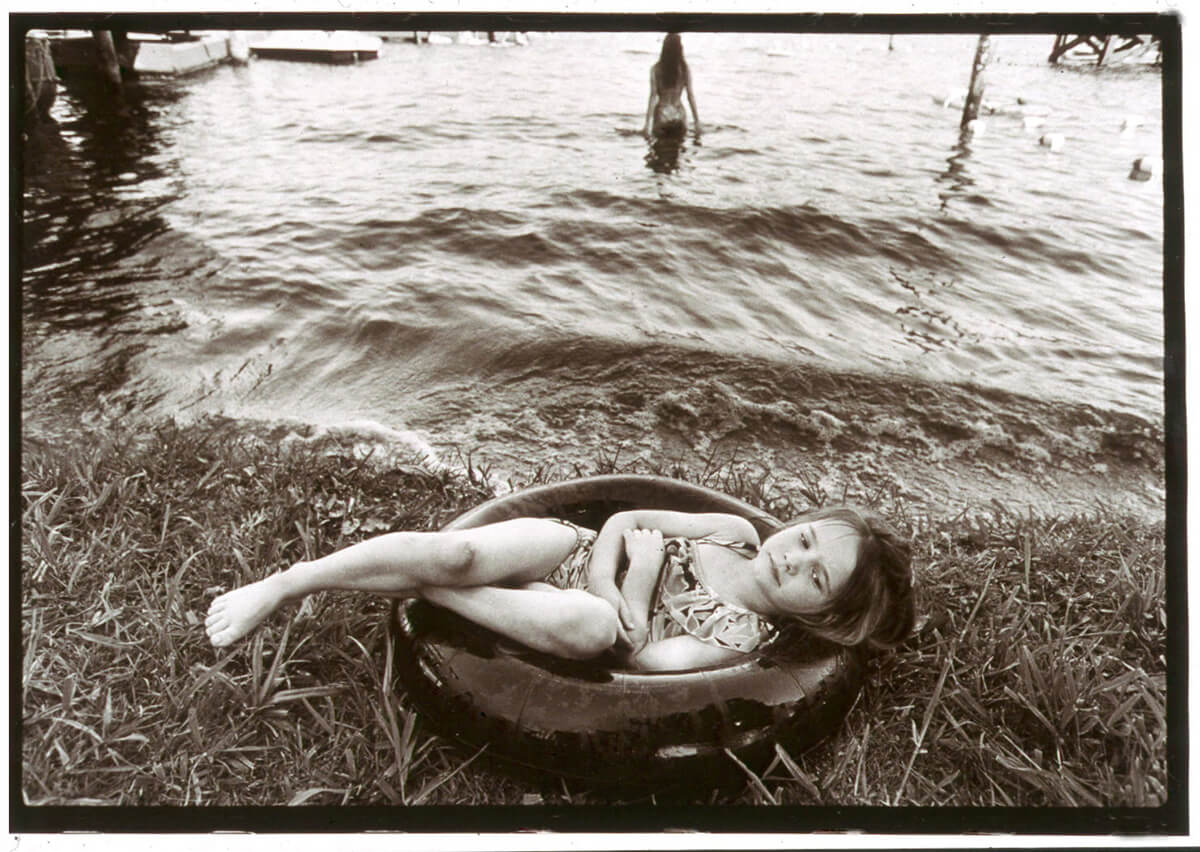

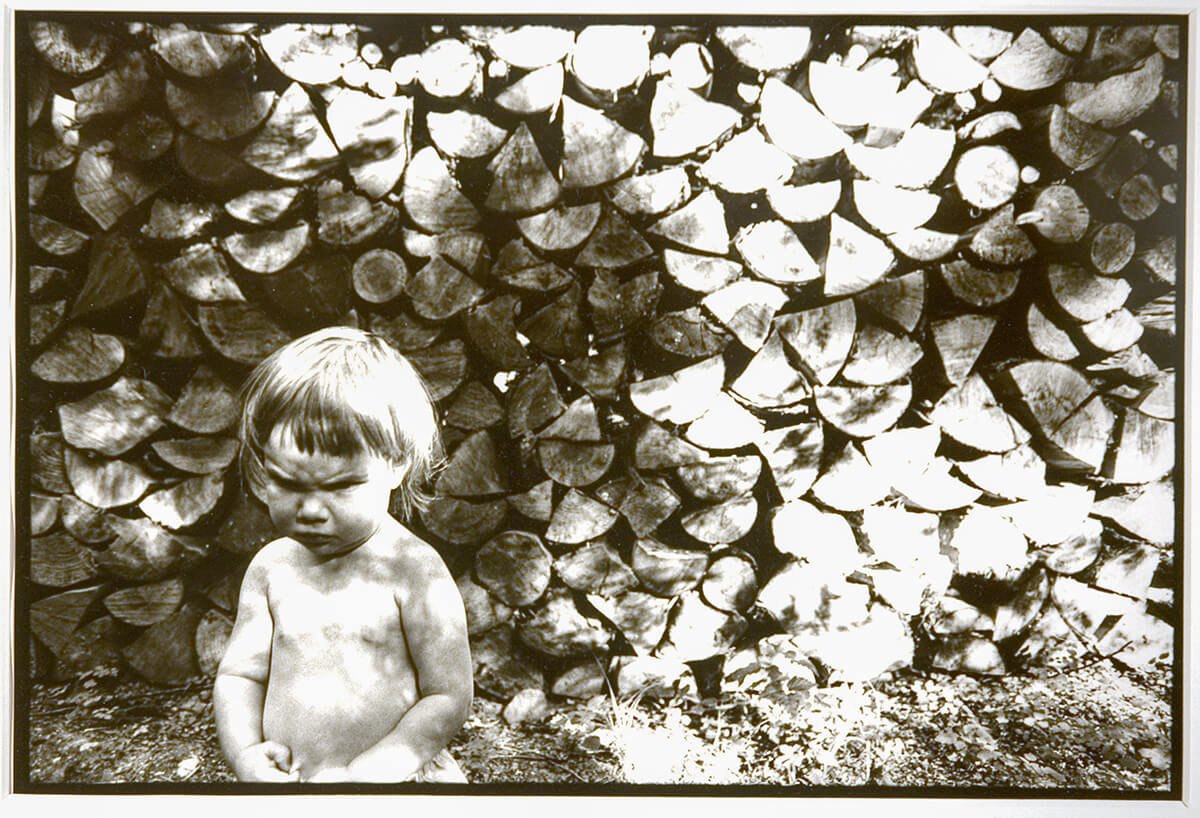

My undergraduate degree is in Psychology and at that time I was actually thinking seriously of becoming a Child Psychologist, so I think I have a fairly realistic idea of what childhood is. It’s a time filled with both great joy and great terror; and when children are “playing”, they’re also seriously “working.” I’ve tried to capture a bit of both those emotions and those attitudes in the photos I’ve made of my own and others’ children, and I have never consciously tried to make a photograph that had such limited appeal that it would only be appreciated by one particular family. I’ve tried hard to get into the world that children immerse themselves in when they are interacting with one another and let the truth of the moment be the guiding factor in an image.

This hasn’t always been easy for my wife or the parents of other children I’ve photographed, who would sometimes look at an image that I had printed and would either be appalled by how dirty the kids were in the photograph (“Couldn’t you have cleaned them up a bit before you made the photo?”) or by whatever activity they were engaged in (“Oh my God! You let the kids do that?!?) when the photo was made.

THE FIRST LESSON – BOB’S WINNING IMAGE

LIGHT AND DOUBT

RITES OF SPRING

Do you have a favorite image or two from that body of work? What is it about those ones?

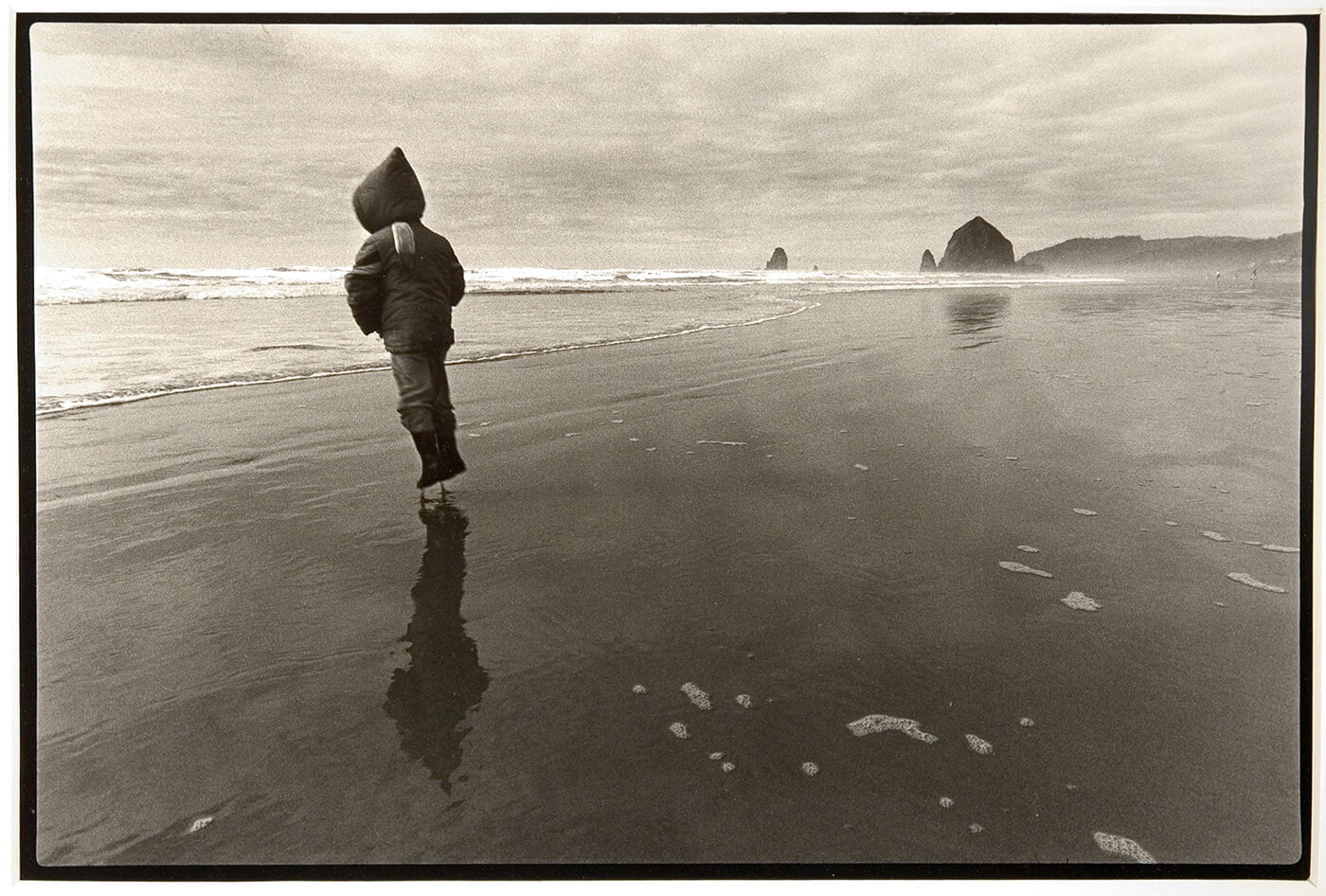

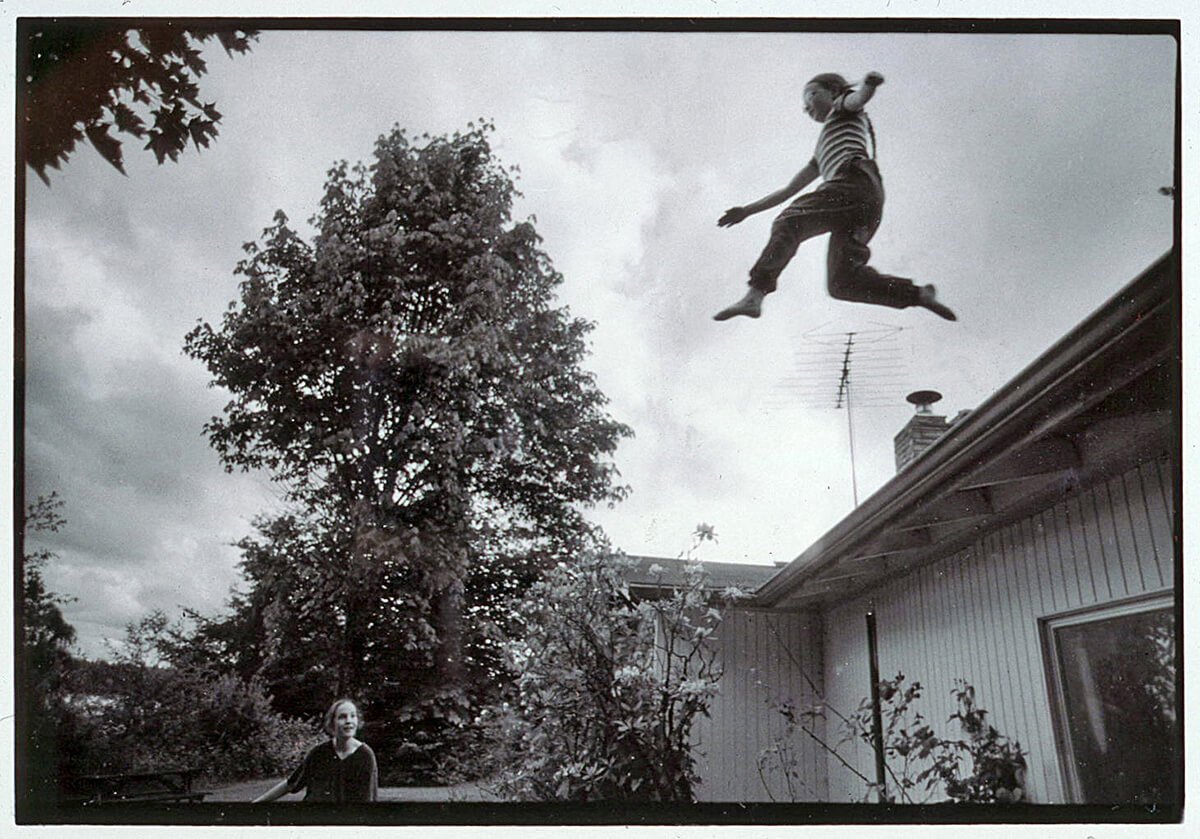

I have two distinct favorites from the “Visual Diary” series. The first one is entitled “The Lightness of Being” [below] and it shows my son when he was 4-years old on a beach on the Oregon Coast. It was a cold, semi-blustery day, but the kids were so enchanted by being on the beach that the weather was simply immaterial to them. At one point, my son gave a little leap of pure joy and the photo captured him at the apex of that leap; so it looks as if he is lifting off the earth and beginning an ascent into the heavens. That sense of joy—of exaltation—is one of the essences of childhood.

My second favorite is entitled “The Willing Captive” [below]. It’s something that I saw as I was pulling into my driveway on my drive home from work one day. My youngest daughter was standing in a wagon and tied to a pole while her older brother and sister were on the lawn in front of her having a fight with swords they’d made out of sticks. To show you the kind of disciplinarian I am, I jumped out of the car (with my camera, of course), took two photos of the scene, and then untied my daughter and scolded them all for doing something so dangerous. Their explanation was that the older two were playing “pirates” and they had excluded their younger sister from the game; subsequently, the youngest one had actually tied herself up so that she would be allowed to play with them, since she then became the captive over which the other two were fighting.

I love the entirety of the composition of that second photo; it’s almost like a religious painting of a martyred saint. But I also like the expression on my daughter’s face and the fact that this is the role she chose for herself in the game they were playing. The image speaks to me of just how dangerous and tenuous and beautiful childhood is.

Particularly with the advent of social media, there are debates about putting photos of children online especially young ones who won’t have given their consent. Is that something you’ve thought about? It is something you’ve discussed with them as they’ve gotten older?

It’s an issue that I’ve thought about a lot over the years. In the late 1990s I showed a number of images from the series on childhood to a woman who ran a photo gallery in New York. She cautioned me at that time not to succumb to the siren’s call of someone wanting to buy one of those images for publicity purposes; she warned me that I would have no control over how the image was used, and that a perfectly innocent image of my kids could end up being used for all kinds of nefarious purposes. I took her advice and never sold any of my photos of my kids.

More recently, just this past month in fact, I got a similar warning from one of my nieces who has worked with the NSA. I had been posting old photos on Facebook of my kids, some of which showed them either partially clothed or entirely naked when they were very young, and I had assumed that only my friends and family could see them. But my niece called and told me in no uncertain terms to quit doing so and to take down the ones I had already posted; she had first-hand knowledge of how such imagery can be co-opted and (like the publicity images mentioned above) used on sites that might feature child pornography. I was stunned by that news and quickly did as she asked. Still, it makes me sad because some of those photos are ones that I really love, and I know they’re strong photos that ought to be shared with a much wider audience.

THE LIGHTNESS OF BEING

THE WILLING CAPTIVE

TROUBLE IN PARADISE

You’re a retired photography professor. Tell us a little bit about that, and the bearing it has on your own photography practice.

I had the great good fortune for the last 40 years of my teaching career to work at a place (The Evergreen State College) which put a premium on teaching and learning. Thus, the faculty there had no “publish or perish” mandate—which for an artist translates into “exhibit or perish.” Instead, the emphasis was put on teaching effectively as well as working and learning outside one’s avowed discipline by team-teaching interdisciplinarily with folks in other fields. Subsequently, I got to teach with physicists, geneticists, literary and language scholars, journalists and historians, as well as other artists. That had a tremendous impact on my work as I was constantly being challenged to get outside my comfort zone and take great risks; that, in turn, allowed me to fail miserably at something (often in front of students) and take it as a learning experience.

I was also able to travel abroad fairly regularly, sometimes alone but more often with groups of students; these trips lasted anywhere from five weeks to several months. As a result, I was exposed to a number of different cultures over extended periods of time and was able to make photographs in places as diverse as France, Greece, Italy, Japan, and Mexico.

Both of these experiences had direct and indirect bearings on my own photographic practices. I learned how to take more risks with my own imagery in order to keep it (and me) from getting stale, and I learned to appreciate wherever I was (even my own backyard) as a visual cornucopia.

What’s the most important lesson you’d try to impart on your students?

The best advice I gave to students is that each of them has a special knowledge of something that they can see and portray better than anyone else. They need to find what that thing is while they’re in the process of learning how to make photographs and then pursue it doggedly. To that end, I gave them the same advice that is often given to young jazz musicians: “Imitate. Integrate. Innovate.” In other words, first, find someone’s work you love and try to imitate it; you’ll find that it’s impossible, but you’ll learn a lot in the process. Next, take the best of what you’ve learned from imitating others’ work and integrate it into your own aesthetic sensibility. Finally, do something totally new and start producing work that is uniquely your own.

INNER WORLDS

STORMY WEATHER

A LEAP OF FAITH

And these days what subject matter most excites you? Where do you find inspiration?

The world itself excites me. Period. I am continually amazed by the beauty of the things that I see around me every day, and that includes everything from traditional subject matter, like the scenic landscapes and wildlife that surround us, to the darker side of life, such as road kill and urban decay. I find inspiration simply by going out with a camera and keeping alert to my environment.

And finally, what’s keeping you busy right now Bob?

As I mentioned above, teaching at Evergreen was great because of what it allowed me to do as a photographer and the opportunities I was afforded to stretch my aesthetic sensibilities by working with other faculty outside of the visual arts. The downside, however, was that since I felt no real pressure to exhibit my work, I really didn’t put much effort into that arena. My teaching schedule was so intense that I simply didn’t have either the time or the energy at the end of any day after work to go into the darkroom and spend a lot of time printing. Over the years I have been lucky enough to exhibit different bodies of my work or different single images from time to time in one-man and group exhibitions, but never in any concerted manner.

What’s keeping me busy right now, then, is simply going through a backlog of over 40 years of photographs and scanning all my negatives so that I have digital copies of them. In doing so, I have come across some images that I either had forgotten about or had simply not seen and appreciated well enough when I first looked at my contact sheets; some of those images are real gems, I think, and I look forward to being able to print them in the future.

I’m still actively making new images, always looking for something new while also continually adding to several different series that I have been working on for decades. I still carry a camera with me wherever I am.

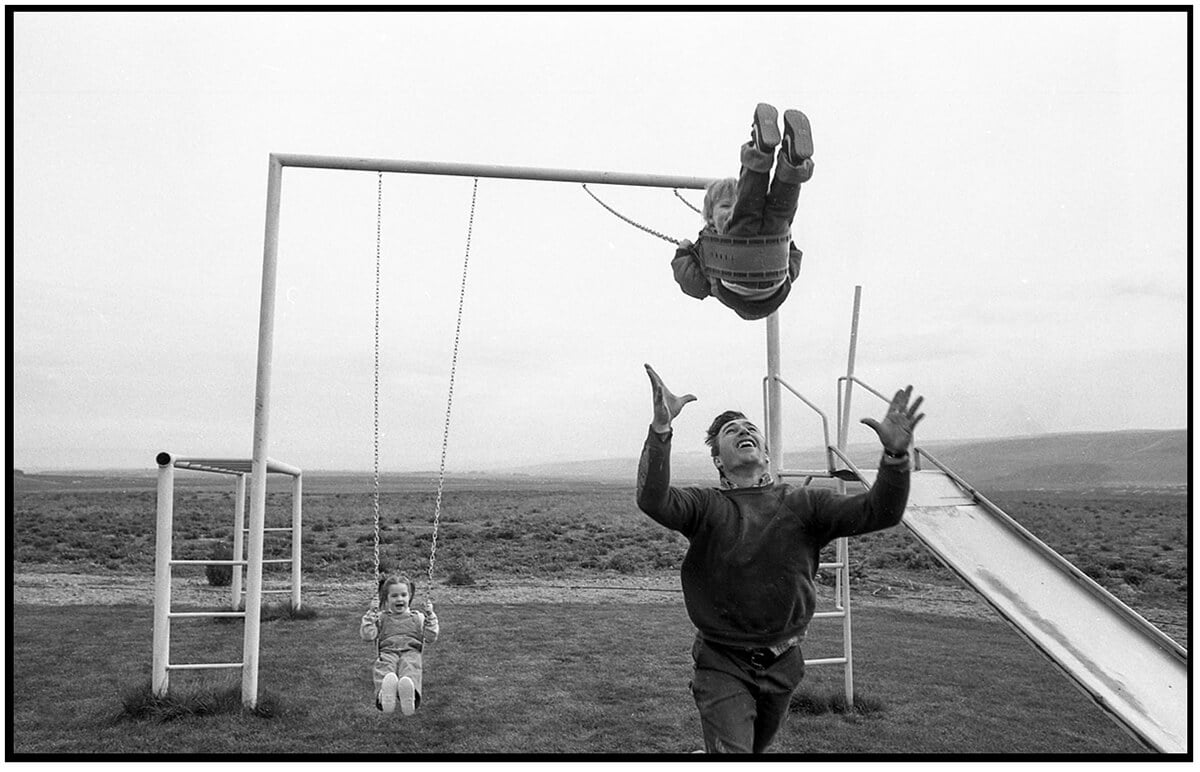

THE SWING

SUNDAY MORNING BALLET (DANCED TO MARTY ROBBINS’ EL PASO)