FEATURED STORY

Found Polaroids

BY Kyler Zeleny

The intimate lives of complete strangers

“These images allow us to glimpse into a fictional, but paradoxically universal, reality that can only be found through storytelling”

Since its inception in 2011, the Found Polaroid Project has amassed an archive of over 6,000 orphaned Polaroid images. Beyond the nostalgia-driven allure of uncovering and sharing images in this iconic format, the premise of the project is simple – to give them new life by asking creative minds to use them as a jumping-off point for fictional stories.

At once eerily distant and warmly familiar, the stories, and the Polaroids that inspired them, have a way of not only transporting us to a different time but also into the intimate lives of complete strangers. By exploring a colourful range of narratives and emotions, these images allow us to glimpse into a fictional, but paradoxically universal, reality that can only be found through storytelling.

Having recently published a collection of the best stories so far through the independent publisher Aint-Bad, we invited founder Kyler Zeleny to share five outtakes with us – stories that didn’t quite make the final edit. As Dr. Peter Buse puts it so eloquently in his introduction to the book, “it’s not the truth of each Polaroid that is revealed, but its potential.”

You can purchase the book via Aint-Bad, or visit www.foundpolaroids.com to view more stories, or choose a Polaroid and contribute your own.

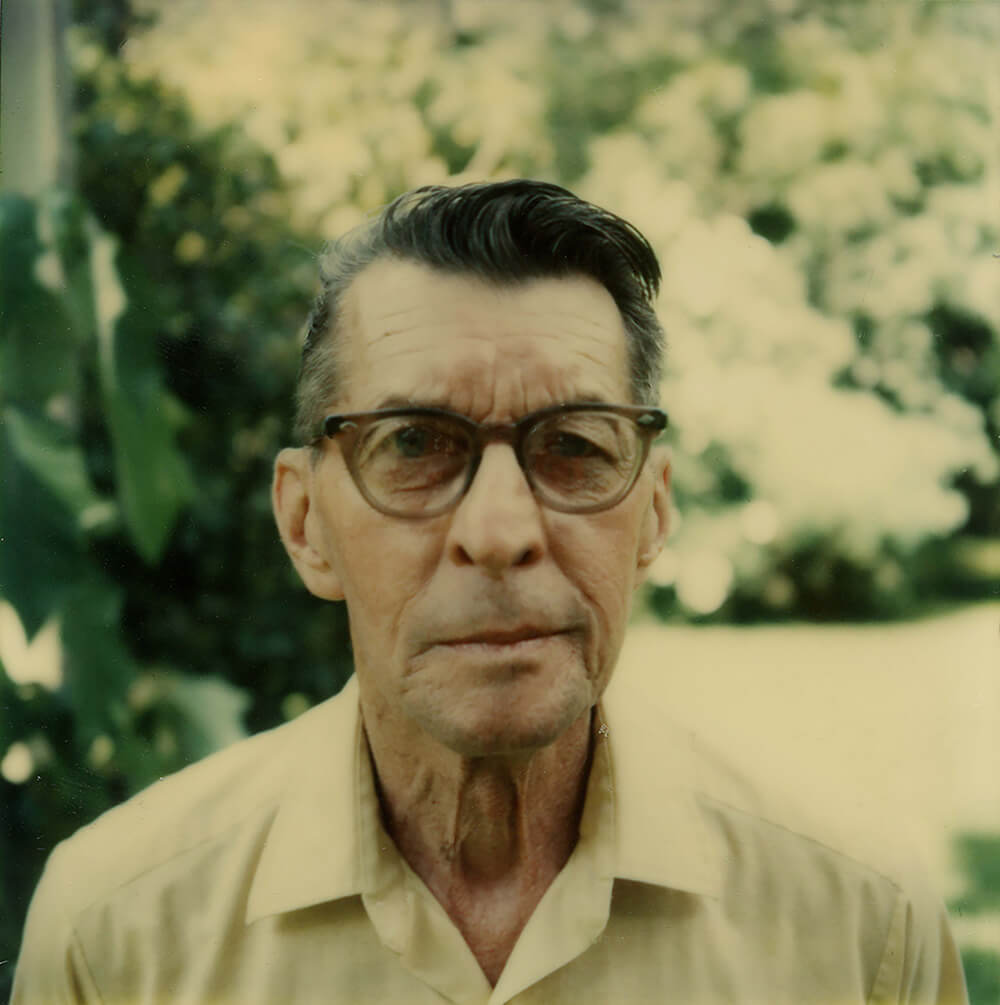

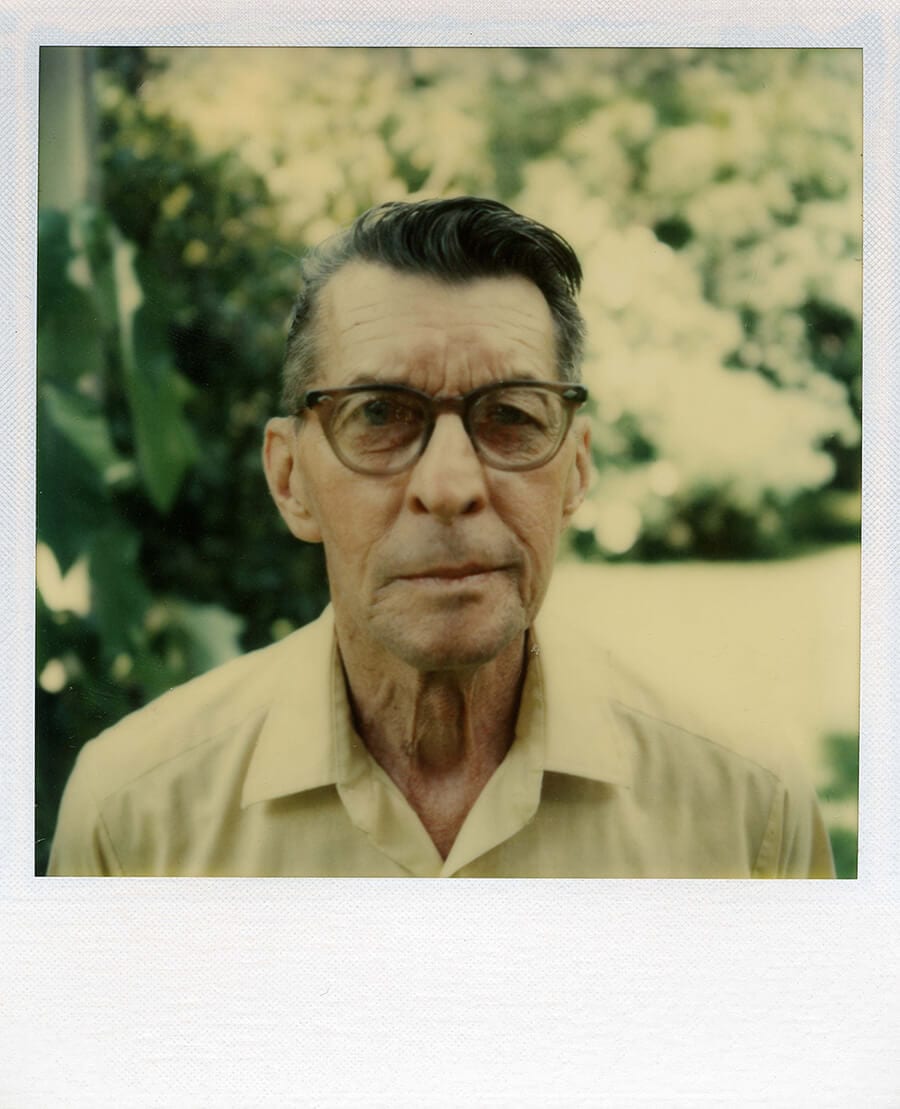

I took this picture of Grandma. She was a sport and great fun. At least I thought so. Everyone called her Babs. Her name was Barbara. She didn’t like “Grandma” so Babs seemed to be an acceptable alternate when all the grandkids started coming along. She loved to travel. Grandpa used to joke that if you gave her five minutes notice, drove by the house slowly and left the back window down she’d throw her suitcase in and jump in after it. She always winced a little when he pulled that one out but he never wanted to go anywhere. “Someone has to feed the dogs,” he’d say. “You’re just cheap and a fuddy-duddy,” she’d throw back at him.

This was the trip we took to Six Gun Territory. I don’t think it’s there anymore. Newer, fancier, flashier, more expensive places have taken its place. Mom always seemed a little put out when Grandma tagged along. I never knew if it was because she felt like Grandma was in the way, or if she was just jealous because Dad would pay attention to her. Grandma did snore, and she had that constant cough. It was probably just habit. “Drainage,” she’d say, then clear her throat. When she was with us we usually got adjoining suites. Babs and the kids in one room, Mom and Dad next door. Maybe that made the trip more expensive. She always agreed to help pay but Dad would never let her. “Double holiday for me,” he’d say, and grin. Mom always turned red at that one.

I was sick this day. Babs agreed to stay in with me so the others wouldn’t miss their fun. It was a long, hot drive from Chicago to Central Florida. Anything that slowed down the pace or got us off our itinerary was a signal for Mom to do her little rant.

“You’re going to get in trouble if you use up all those Polaroids,” Grandma would say every third picture. I didn’t care. I bought the film; it was mine to waste. But, how can a captured moment be wasteful? I’m happy to still have this picture. I wish we still had Babs.

Story by Steven Yancey

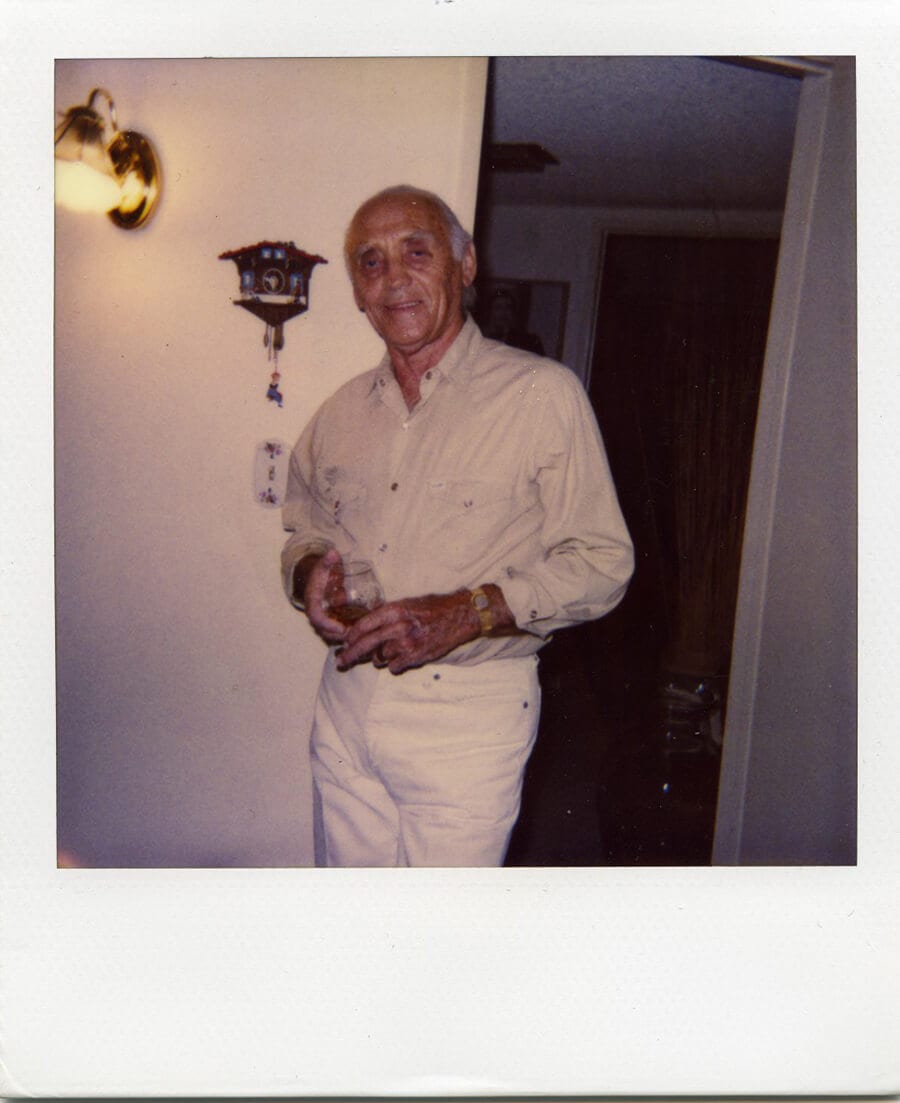

He’d been in the war for Christ’s sake, bombed the hell out of islands in the Pacific. Ridiculous to be so nervous. He didn’t used to be. He’d enjoyed his wife’s friends and they’d seem to like joking around with him. This was different. There was no safety boundary of wives and husbands. There was no more wife. Radiation and chemo had bombed the hell out of her. So now it was just him with no ring to hide behind. He’d tried flying solo but the days were long. Even that yappy dog his daughter had given him didn’t break the silence enough, not in the right way. Noise doesn’t equal companionship. He doted on the little dog and it was helpful for meeting neighbors but nothing was the same as someone wanting to know how you slept the night before, what you thought about the movie, when was your doctor’s appointment. He’d thought he’d never marry again because no one could be his sweet Peg, but Peg had told him, “You’re the marrying kind. Besides, she and I will have a good laugh about you in heaven.”

He ironed his shirt and pants, pants should have a crease. Both white, at least he looked the hero. He’d invited her over to his house. She lived in a tiny apartment. He couldn’t stand tiny apartments. He’d always cooked a great steak, knew just how long for every taste. He hoped she didn’t like it well-done. Might as well eat shoe-leather, he’d always said. He reminded himself to be open-minded, people can like their steak different ways. He knew red wine was fashionable with steak but it was too strong for him nowadays. He needed his wits about him. When the knock came he was ready.

She cleaned up nice. He’d met her at the gym so didn’t know. She didn’t seem nervous at all. Her husband’s been dead five years so she must’ve had lots of practice.

She’d ordered her steak medium-rare. She laughed when he’d smiled.

“Glad you approve,” she said.

Story by Wanda Harding

He saw long stalks of corn formatted squarely atop the Tennessean plains. They flickered only a few feet from the window of his old Electra, and the slim rays of sunshine caught his eye, reminding him of the unimaginable days following April of 1930.

Following the Crash, his father’s grocery went out of the business, forcing him and his family to secede their quaint Tennessee life to the winds of Chicago, picking up laborious jobs from Top Hats and bartering with other dirty faces for soap on the street corners (something he was cunningly good at). It wasn’t so much the gnawing awareness of his own poverty that bothered him; his family was poor enough in Tennessee.

It was how he missed the Irish girl who’d come in his Father’s grocery every Thursday. She would saunter in with a quarter for milk, and a nickel for her dark chocolate Hershey bar. He remembered the insignificant details because, well, they weren’t insignificant to him. She always wore a scarlet dress, with a re-sewn lace white collar fastened up to the nape of her neck, paired with an old tinker of a watch. It didn’t tell the time, nor was it supposed to she always said.

“Why doesn’t it work?” He finally asked her.

“Time doesn’t stop ever, does it?”

“I s’pose not.”

“And the watch’s job is to tell time, right?”

“That seems to be the case.” He let out a stifled chuckle, unaware of whether or not it was an actual question.

“So the watch has an impossible goal of keeping time forever. His job will never end, no matter how many times he’s repaired. I gave him an early retirement. Now he just rests on my arm stress free.” She confidently announced to him.

He still thought it would be nice to know the time.

Story by Jacob Bridgman

He’d been staring through the kitchen curtain every now and again for days, threatening himself to do it, and today he did: Sunk down in the burgundy seat of the Buick and shut himself inside, fired her up and drove 14 long, sports-radio minutes on Route 9 to Shane’s U-Drive-It, right there at the northwest corner of Mulholland, and pulled in quick next to the spit-shined Minnie Winnie he’d been eyeing since Pamela up and left five Sundays ago with the Dachshund and hadn’t as much as called since.

He cut the motor and turned to look and its big pinstriped belly filled the window. A ‘78 model, he knew. Twenty-four foot, VCR included. Not a ding. He’d been thinking about the dog. The last thing she did before she skedaddled, besides shove her dry cleaning in the trunk and storm back inside to rip that lamp out of the wall, was scoop the dog off the lawn. She kicked up gravel on the way out and and yelled something and he bent his ear but it was God knows what. She didn’t even take the kibble, and now the house was filled with such a quiet that he kept hearing himself move.

Inside, Shane was running his mouth. He’d go back and lock up, put the Coors on ice, strip the bed and pack his laundry inside. Ask Danny to keep an eye out. Take it down the street and bring the tires up to 32 PSI. He drew all the air he could into his chest and let it go. He’d take the key down from the back doorframe, and that’s tough. Her mother would have tanned her hide.

“Must be my lucky day,” Shane said, and he pinned another picture to the pegboard with a big banner in permanent marker that said “Our Satisfied Customers!” He grabbed the camera off his desk, wagged his elbow toward the parking lot and bared some teeth. “Let’s do it, my man, looks like your number’s up.”

Story by J. Williams

It’s not like we could plant flowers in the city, anyhow. Like, you’d see those nature shows or inspirational posters in the counselor’s office where a tiny plant poked its flower up through a crack in the dirty, steaming concrete of the sidewalk and that was supposed to make you feel good.

What they didn’t show you was three seconds later when some asshole stomped on the flower, not thinking about nature or beauty or love, but probably just hurrying home from work to make a sandwich and jerk off on the couch.

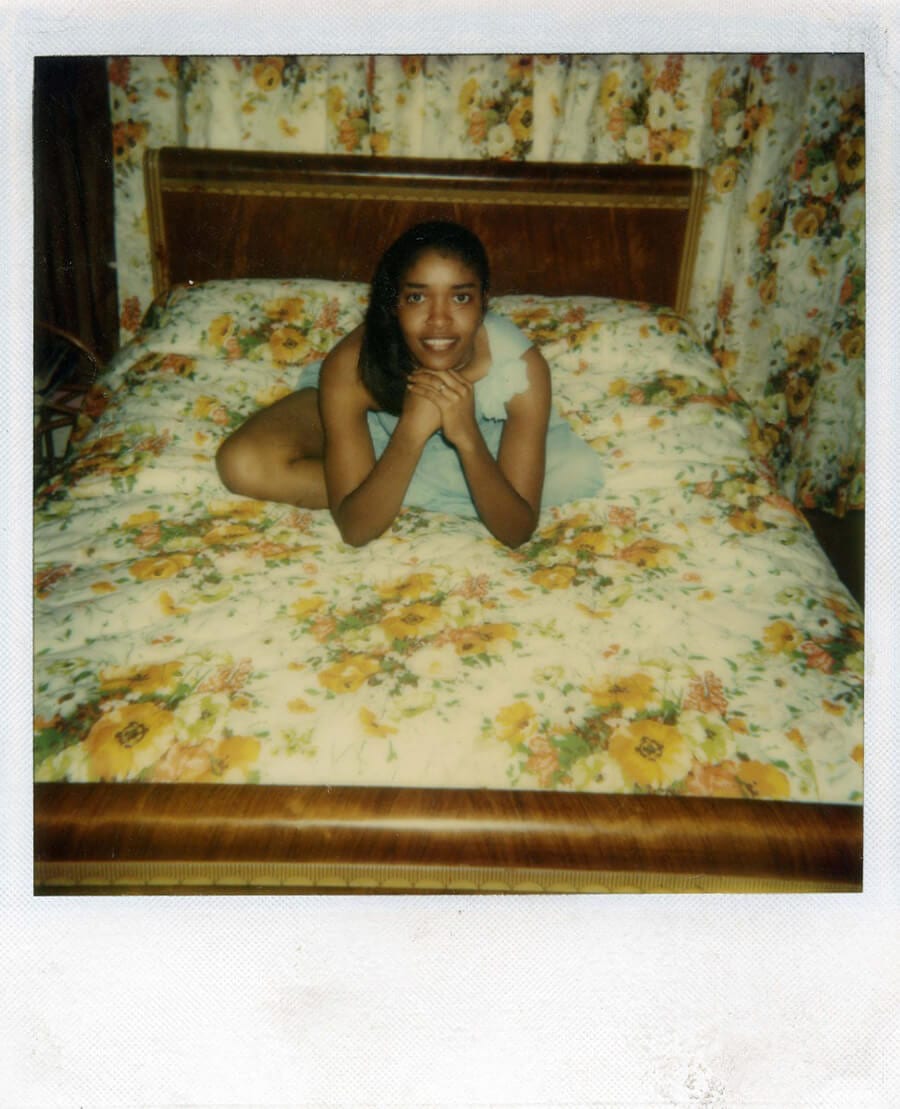

Maya wasn’t mine, but I knew she loved flowers. And because I loved her, I did what I could.

“Pose for me, baby,” I told her and she squirmed but said nothing. Maya wasn’t a talker. I made sure of that when I picked her. And I loved her so much that when I found all the floral prints for the hotel room, I put them up while she was at school, knowing she’d be happy when she returned.

I lived to make baby girl happy. She did nothing but bring me joy.

“C’mon, girl,” I told her, but still, she resisted. Stalling, she tried to get up from the bed, but she didn’t get far.

“Maya.” Just her name spoken aloud was enough. Man, I loved that child. She stuffed a pillow into her lap and beamed up at me. That white smile up against those pretty flowers was enough to make my head spin a little bit.

Story by Devon Fulford