FEATURED STORY

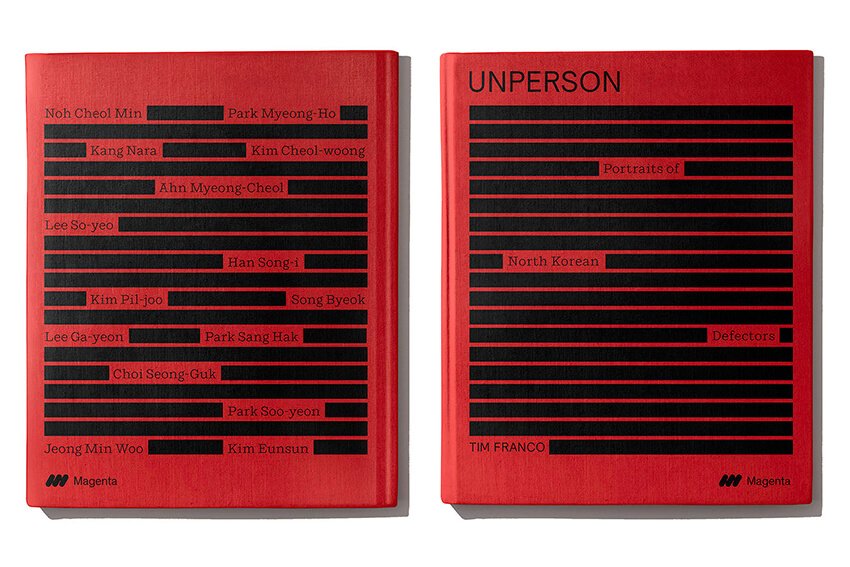

Unperson: Stories from North Korea

WITH TIM FRANCO

Portraits of North Korean defectors

This article was originally published in June 2018. Since then Tim has completed the project and produced a book that is currently open for pre-orders at this link. He has also created a stunning short film which gives viewers a behind the scenes insight into the project and can be viewed at this link.

French-Polish photographer Tim Franco has spent a decade examining the urban and social transformations taking place across Asia – from the burgeoning alternative music scenes and LGBT communities in Shanghai, to the rapid urbanization of central China and Azerbaijan, and the impacts on those left in its wake. He documents significant cultural trends, but through the eyes of individuals, understanding that personal stories are often the most engaging medium for probing complex societal events.

For his most recent series he ventured further east to South Korea, in a bid to better understand its sibling to the north; the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, or more commonly North Korea. This is a country rarely out of the news, and yet one shrouded in mystery, intrigue, and perhaps substantial hyperbole. True to his modus-operandi, Franco’s way to probe deeper towards the truth, is through people. He met with North Korean defectors – those who have escaped across the borders to China and South Korea – interviewing them, and asking them to sit for portraits.

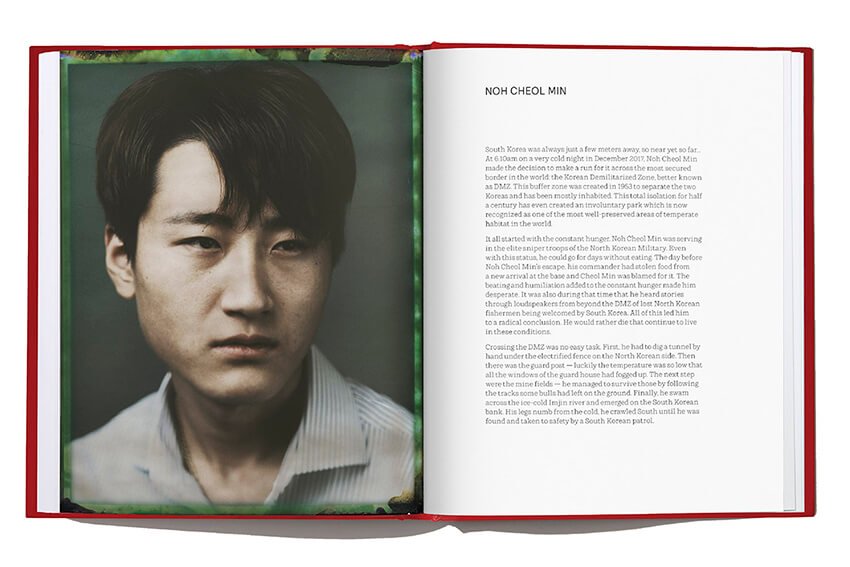

His chosen title for the series is ‘Unperson’; a reference to George Orwell’s seminal dystopian novel 1984, and a term used to describe someone whose records have been erased. Like those unfortunate ‘unpersons’ in 1984, Franco’s subjects have left a life that they can never return to, their histories essentially expunged. They are not supposed to exist, and yet through hardship, determination and some luck they live on in a new world. The idea is aptly symbolized in the innovative analog method he uses for their portraits – through a series of complex trial-and-error chemical processes, the defectors’ portraits are revealed from the negatives of Polaroid film, in a manner in which they were never supposed to exist.

Here, Franco shares some more information on the project and his rationale, along with a selection of defector portraits and stories. These are abridged versions, and you can read them in full at www.timfranco.com

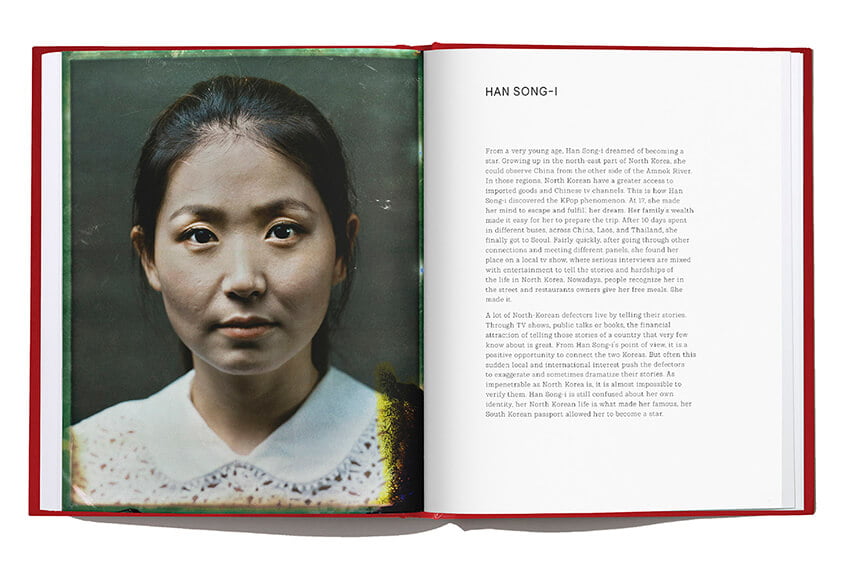

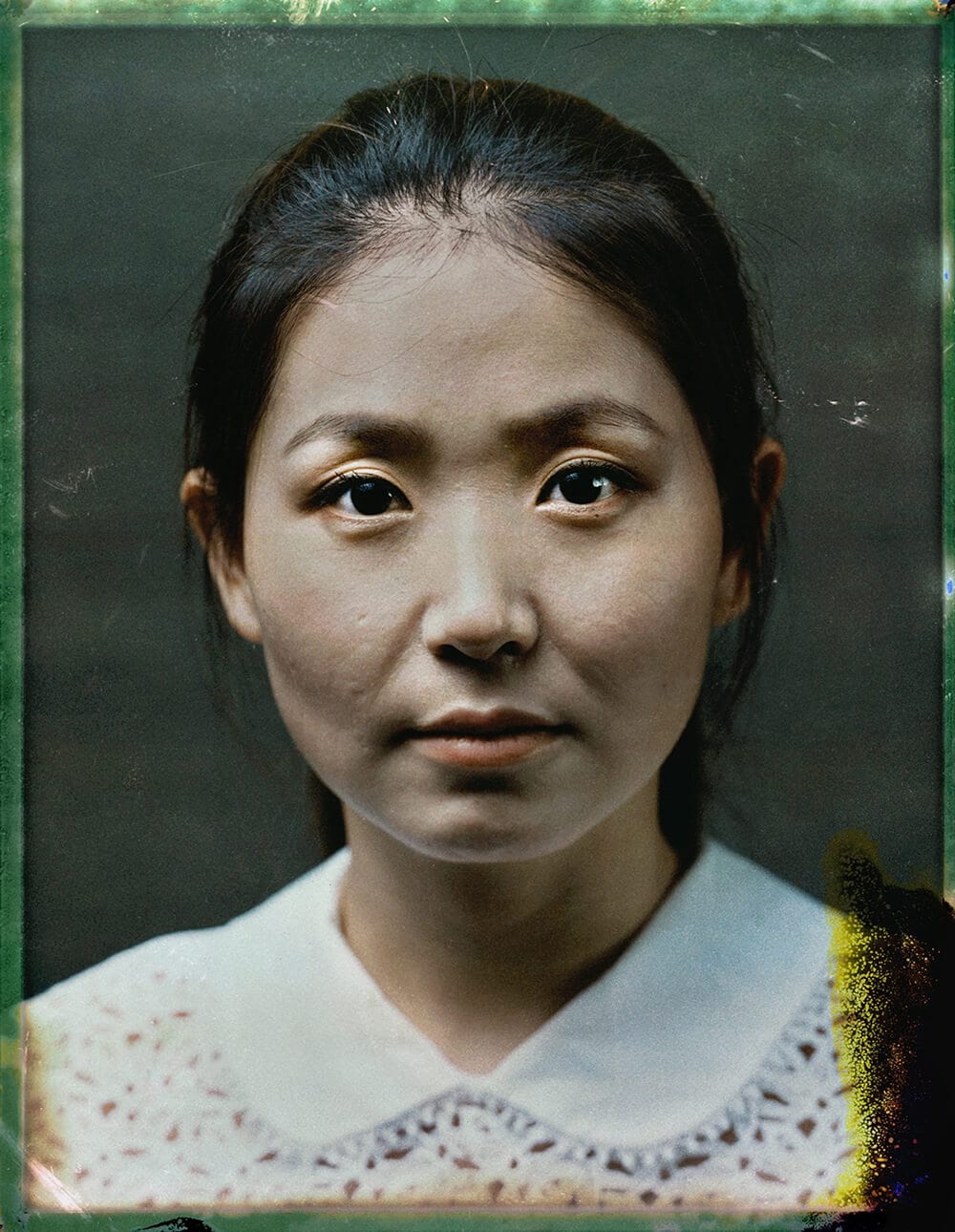

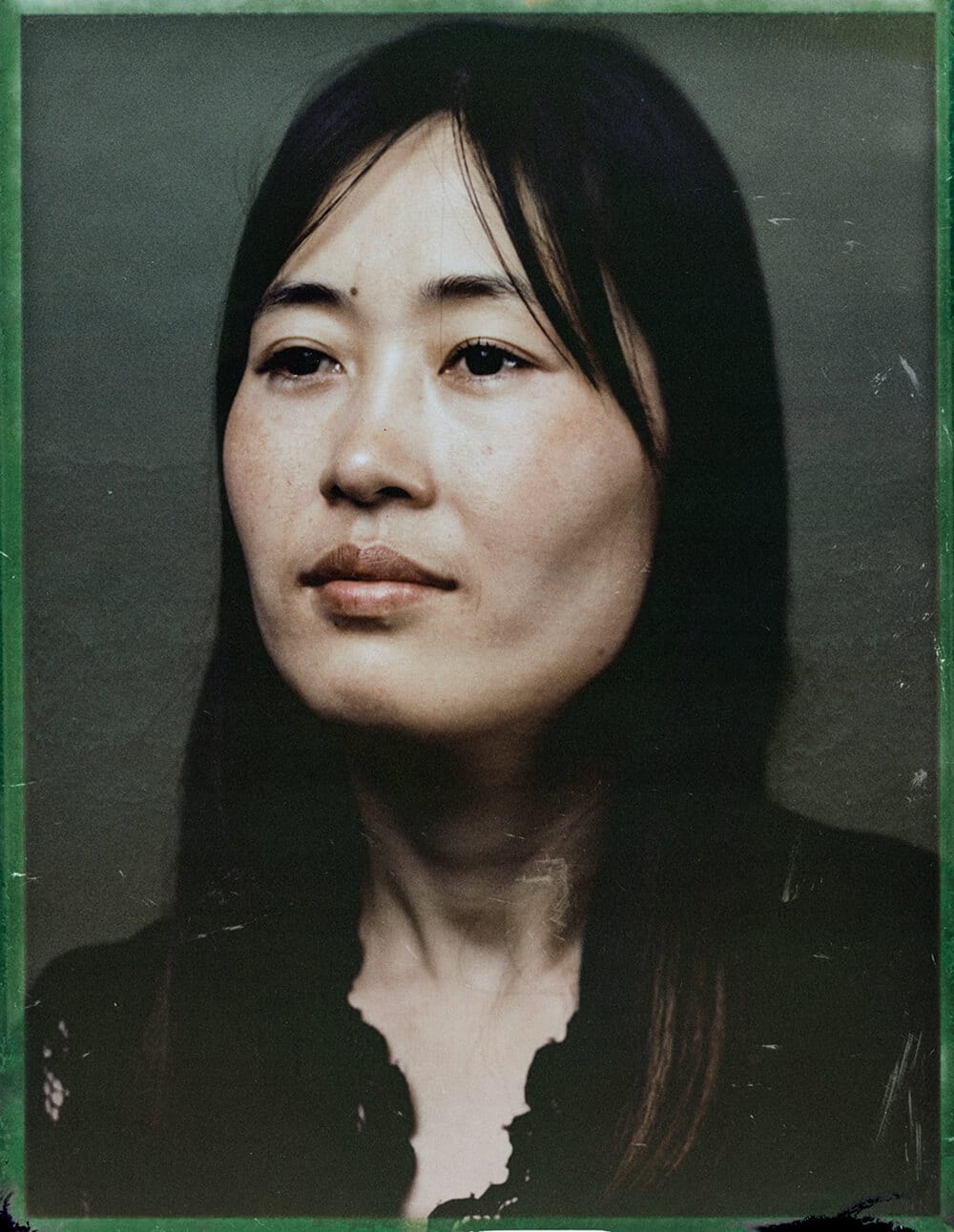

Han Song-i

From a very young age, Han Song-i dreamed of becoming a star. Growing up in the north-eastern part of North Korea, she could observe China from the other side of the Amnok River. In those regions, North Koreans have a greater access to imported goods and Chinese tv channels. This is how Han Song-i discovered the K-Pop phenomenon. At 17, she made her mind to escape and fulfill her dream. Her family’s wealth made it easy for her to prepare the trip. After 10 days spent in different buses, across China, Laos, and Thailand, she finally got to Seoul.

Fairly quickly, after going through other connections and meeting different panels, she found her place on a local tv show, where serious interviews are mixed with entertainment to tell the stories and hardships of the life in North Korea. Nowadays, people recognize her in the street and restaurants owners give her free meals. She made it. Han Song-i is still confused about her own identity, her North Korean life is what made her famous, her South Korean passport allowed her to become a star.

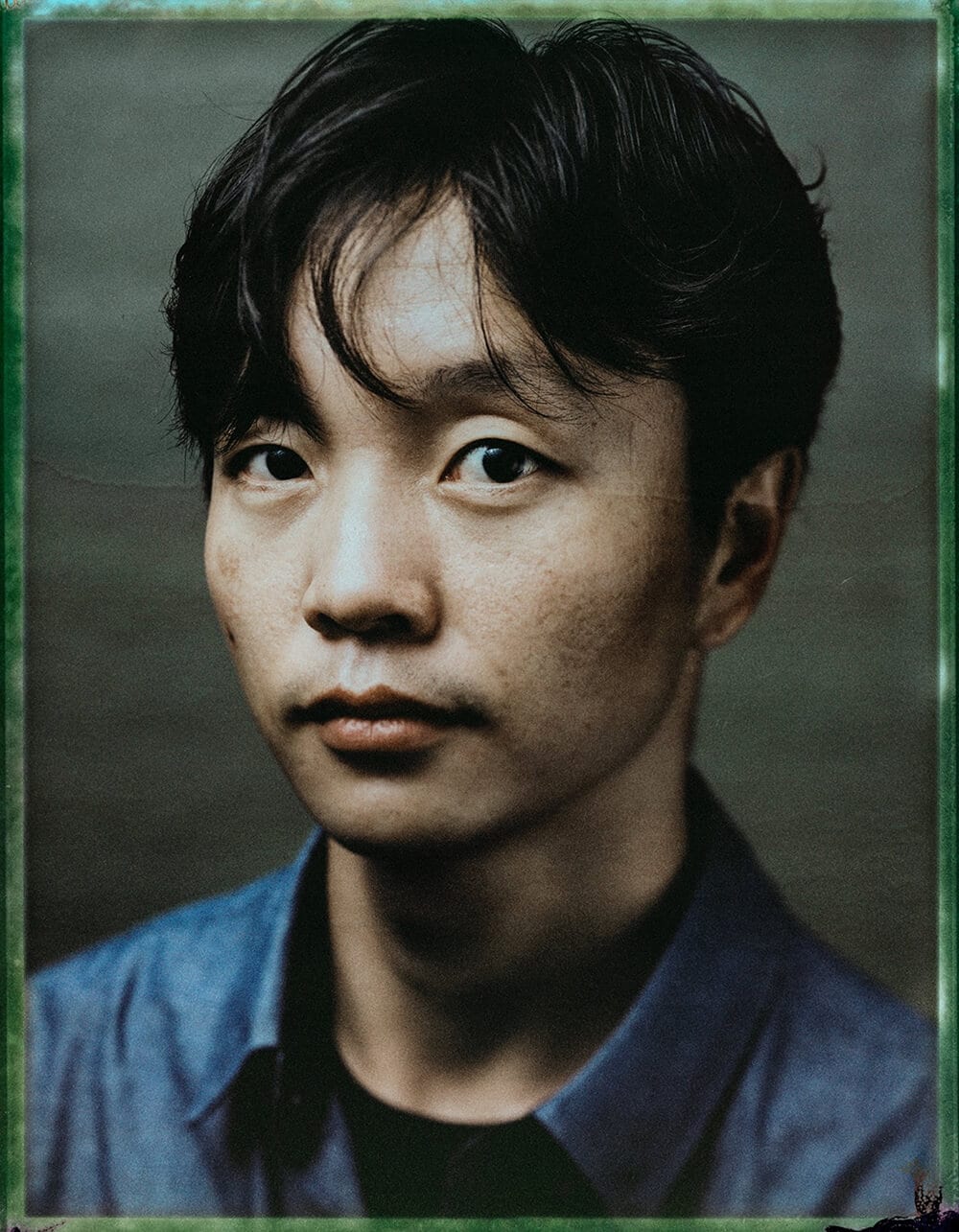

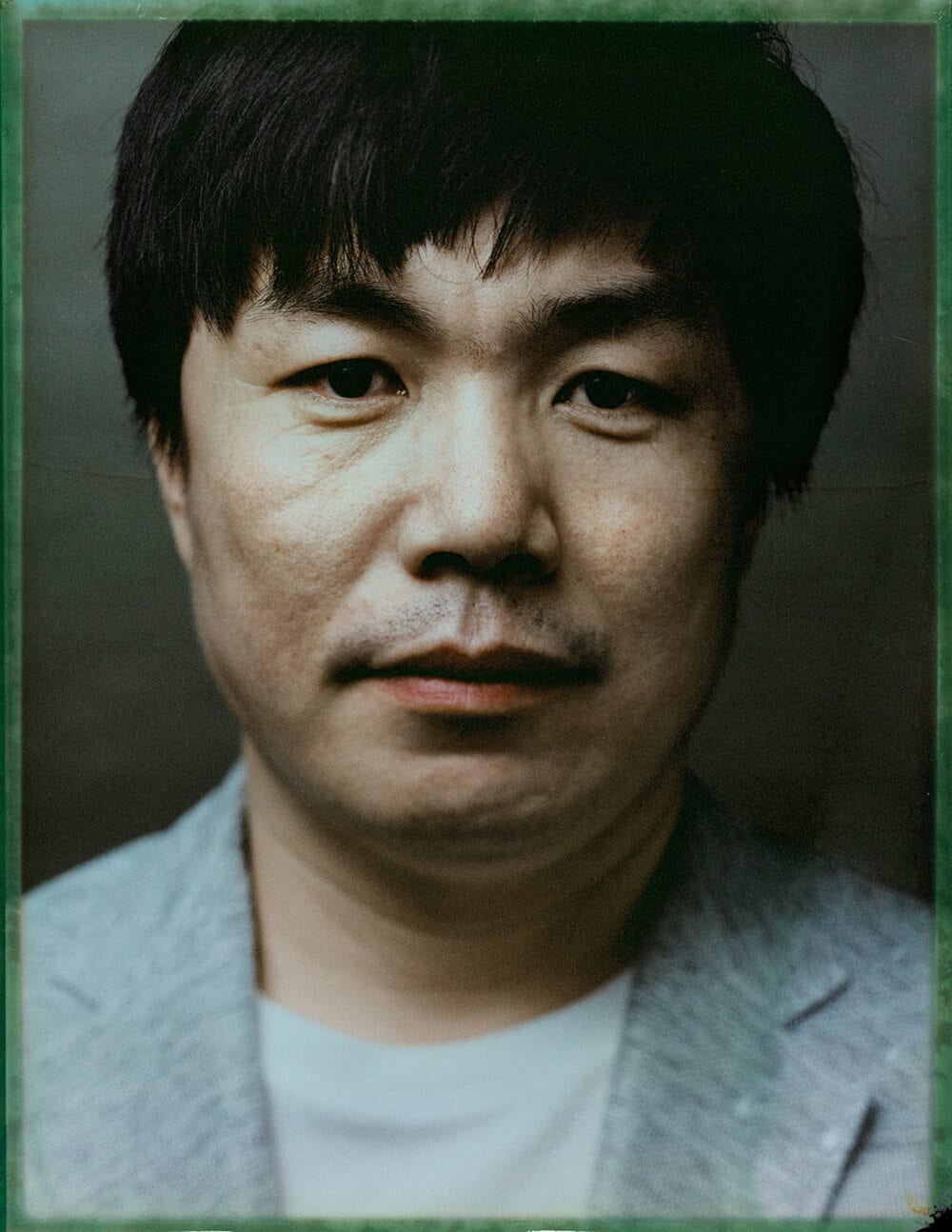

Kim Pil-joo

When Kim Pil-joo was a young boy, his mom was often traveling to China illegally to purchase and sell products. Every time she got back, a smell of candy and sweets was invading their home. He imagined China as a big candy factory. At 12, during a rough year of famine in the country, he experienced a public execution. The man had stolen a copper safety line from a mine and tried to sell it.

It took him two attempts to manage to escape North Korea. His mom was already in China and it was a question of survival. When he finally arrived in South Korea he was first shocked by how he was welcomed by the local government. All his life he was told how evil the South Koreans were. Even though he now lives and studies in the south, he finds it difficult to integrate fully into society and hopes for a unique identity, where north and south are just one.

How did this project come about? How did your interest in North Korea develop, and what was the trigger for starting the project?

Although I lived in Asia for more than a decade, I just recently moved to South Korea. As I started my life here, I looked around for different projects that I could potentially develop. That same year, Trump got elected and tensions between North Korea and the the US, the South, and the rest of the world seemed to reach a new peak. I realized then that I knew next to nothing about the DPRK. I wanted to learn more about the issues that divide and thought that the best way would be to meet the only people who had lived in both the North and the South of Korea.

How easy was it to track down the North Korean defectors? And were there any reservations from them in taking part in your project?

Every year, about a thousand people defect from North Korea, and many of them end up arriving in the South. When I started this project, my idea was to document their lives in South Korea but it quickly proved to be difficult as many of them, especially the ones that accepted to speak on the record, did not want to display their personal life publicly. There is still a strong fear of North Korean spies going after defectors. I had to propose something that made them feel safe. I then had the idea of creating a photo studio in the press center in Seoul where the defector could come in safely for interviews and a portrait session. Most of the ones that accepted had already spoken publicly in the past. A few that I really wanted to portray ended up refusing as they feared for their remaining family members in the North.

It is interesting that several of the defectors’ stories are somewhat melancholy, tinged with a longing and nostalgia for their homeland. Did this surprise you? And in a world where the Western media often ridicules or demonizes North Korea, was it important to you to paint these subtleties?

One of the most important lesson that I have learned during this project is that there is no way to fact-check any stories about North Korea. The integration of the defectors in the South can be difficult as they are often treated as outcasts and immigrants. Often, they find that telling their stories, and making them sound especially miserable, is a good way to make a living. Although I did not pay any of them for the interviews and portraits, some of them asked me if I could, and I know for a fact that lot of media are offering them cash rewards for stories. Some defectors are also creating NGOs to help other defectors and it’s their main income. All of this is to say that it’s sometimes difficult to know what is true and what is exaggerated in their stories. But what came as more of a surprise to me, as I was looking for a diversity of opinions, was to learn how good a life some of them seemed to have had in the North, especially for those part of the Pyongyang Elite. Even more surprising was to find out how unaware they were of the situation in the rest of the country. The same goes the other way around – some of the poorest North Koreans who defected for pure survival only later found out that some of their compatriots were living a pretty standard life in the city. It’s easy as a westerner to get locked on to a few viral videos of defector stories and generalize the whole situation.

As a Westerner living between China and South Korea, you too have left your homeland. Did this have any bearing on you wanting to tell these stories?

I wouldn’t make that analogy. I love France and Europe, even more now that I live in Asia. Anywhere you go there are some big advantages and also some big drawbacks. Anytime I am in Asia, I miss Europe and the same goes the other way around. I am just very lucky to be in a position where I can actually choose to have the best of both. So many people in the current world situation have not much choice but to escape and survive somewhere else where they are not necessary welcome.

For these images you use the negatives of Polaroids. How did you discover this technique, and can you describe the process, from photo shoot to final image? Was a lot of trial and error required, and were some images lost along the way?

Quite a few years ago, when I started to shoot portraits with my large format camera, I heard about this process. I tried it a couple of time back then and completely failed. Last year as I just started gathering information on the defectors I wanted to portray, I met with Cedric Arnold, a great portrait photographer who used this technique on a series of portraits. It motivated me to try it again. At first, it was really bad and took me a few dozen of trial until arriving at something acceptable. The process is still unpredictable but this is also why I like it.

The basic process is actually quite simple – I used a 4×5 large format camera with peel-apart Polaroids. Once the photo is taken, I get a Polaroid image but also a negative paper sheet that is supposed to be useless. The trick is to first shoot the portrait with certain conditions that would made the negative usable, no matter how the Polaroid looks. Then by cleaning the portrait off the back of the negative with chemical agent, only the negative film remains. As the process is quite unpredictable and dirty, you gets this particular look on the images. I especially like the greenish frame that appears around the images themselves.

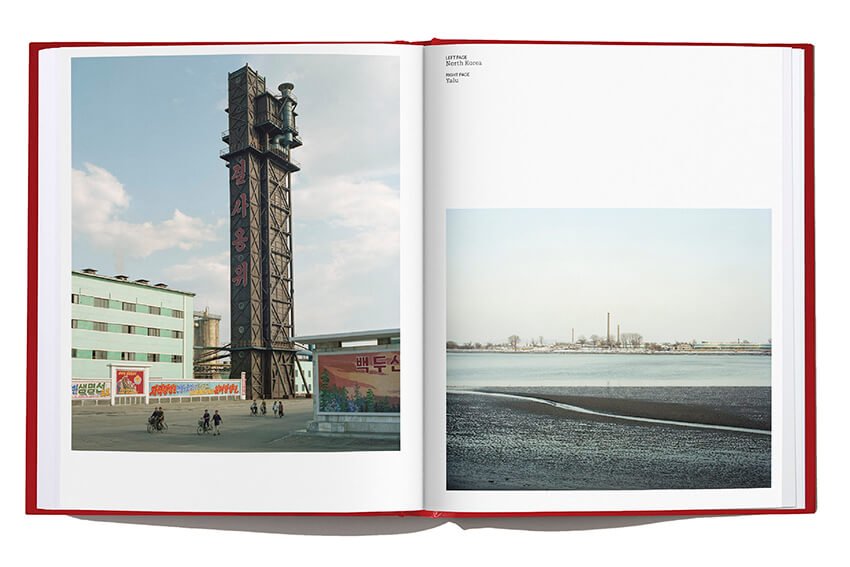

You describe ‘Unperson’ as the first chapter in a bigger story about North Korea you wish to tell. What next?

The second chapter is actually already well under way. For this part I followed the rivers that separate China and North Korea, through which 99% of defectors make their journeys – As you might know, it’s extremely difficult to cross directly to the south through the heavily militarized DMZ. The goal of this chapter is to put the portraits in their environment. The day those defectors crossed that river, their lives changed forever. While shooting those photos, I was amazed to see how easy of a first step it was. In some parts, there is almost no military personnel and the river can be just a few meters wide and often completely iced in winter.

In the last couple of months, everything has changed so quickly that I will have to be smart about what I think will be the third and final chapter.

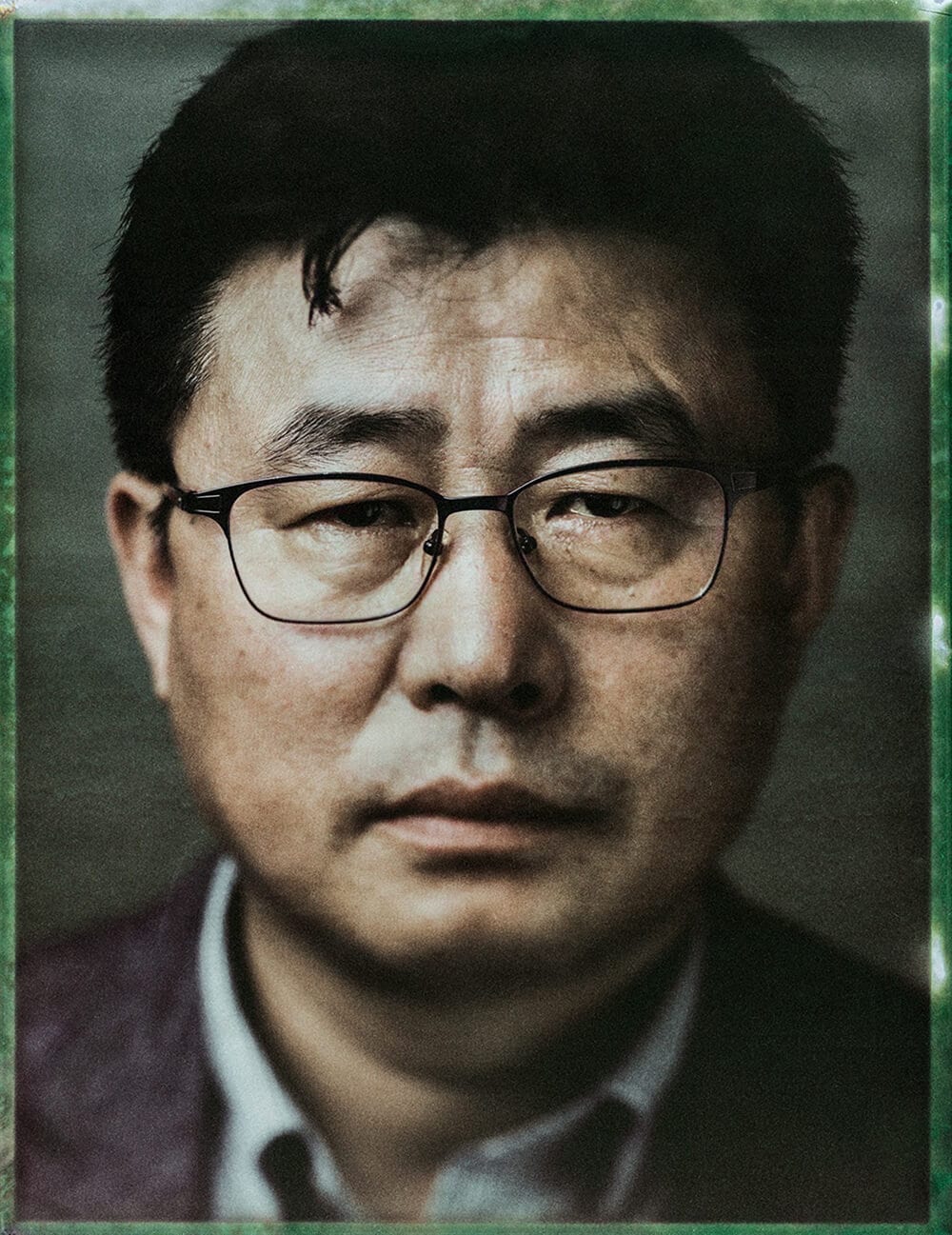

Ahn Myeong-Cheol

One night of 1994, Ahn Myeong-Cheol’s entire world was flipped upside down. Armed with an AK47 and a few pistols, wearing his prison guard uniform, he escaped in a jeep with two convicts. As the jeep was driving towards the Tumen river that marks the border with China, the convicts got cold feet and decided to bail – but Ahn Myeong-cheol had to continue. He swam across the river and hid in a mountain facing the border. From his hiding place he could see about a hundred guards looking for him.

It was 8 years before that night that Ahn Myeong-cheol had gotten his first job as guard in a political prison camp. From the first day, he had been told to leave his humanity behind. All the convicts were traitors or spies for the enemy and even communicating with them was considered a serious offense. Beatings and killings were routine and soon enough, he used a few of the convicts to train his taekwondo skills. After a few years in this position, he got upgraded to driver – bringing convicts in and out of camps. As this new job brought him closer to them he started to interrogate them on the reasons of their conviction but quickly realized that more than 80% of then had no idea why they were even convicted. After 8 years of service, An Myeong-cheol got his first holiday break. He took this opportunity to visit his family. He discovered his father had committed suicide. After a night of drinking, Ahn’s father had started to talk negatively about the regime and then chosen to take his life instead of facing the consequences. Subsequently, his entire family was taken away to a detainment camp. It is at this point that Anh Myeong-cheol finally understood why so many families were among the convicts. As he got back to work, he realized that he would probably be next. That night Anh Myeong-cheol knew that this night would be his last in North Korea.

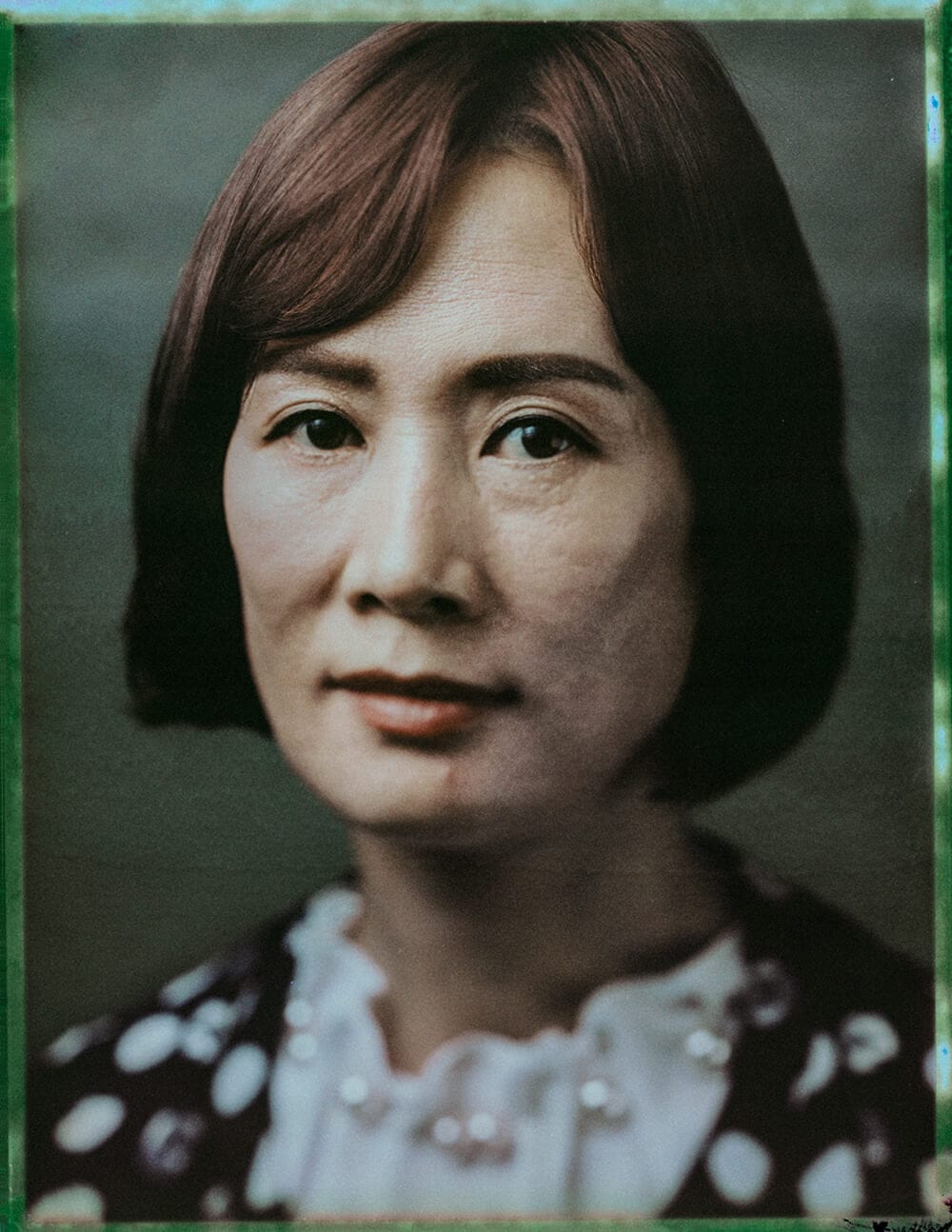

Lee So-yeon

1997 was probably the worst year of the North Korean famine with an estimated number of deaths due to starvation or hunger-related illness from 240000 to 3.5 million from a population of 22 million. It is also in 1997 that Lee So-yeon took part in the military parade in Pyongyang. 20 years after this event – the supposed proudest moment of a military career in the DPRK – all she remembers is the hellish training that still causes her knees crippling pain to this day.

Lee so-yeon had joined the army voluntarily, hoping for a better future, regular meals and a chance to join the Worker’s party. But she faced a very different reality. The famine had reached deep into the military and recruits were fed only half-rations mixed with wild grass. On top of this, sexual harassment and abuse was a daily matter. After 10 years in the military, Lee So-yeon heard about South Korean defectors through an illegal radio channel back in her home village. The stories she heard immediately convinced her to leave. Her first attempt to cross the Tumen river, in her

underwear, holding her only set of dry clothes above her head, her legs bleeding from stumbling on the jagged rocks ended in disaster as she was greeted on the chinese side by human traffickers. Refusing to collaborate, she was thrown back into the river and captured again on the North Korean side. After a year in prison, she managed to gather enough tips from fellow inmates to finally make a second, successful attempt.

Now living in South, Lee Yo-seon still struggle to integrate. The prejudice in society, her strong accent and the fear of North Korean spies still makes her feel that she has not completely found her place.

Lee Ga-yeon

At the time Lee Ga-yeon took the decision to leave North Korea she was completely desperate. Since the death of her father when she was five years old, she and her mother had lived in the most miserable conditions. As she could not afford any education she started farming from a young age, picking mushrooms or vegetables and making barely enough to survive. Despite all of this misery she still believed that this suffering was temporary and that – as everyone knew – North Korea was the best place in the world. But her mother fell ill and Lee Ga-yeon’s hunger became so

unbearable that she had to go look for help to her aunt who was living near the border. Out of desperation, between the lack of food and the need to purchase medication for her ill mother, Lee Ga-yeon decided to defect.

The Chinese part of the trip is often the most dangerous as defectors can be ID-checked and reported at any moment, risking being sent back to North Korea to a certain prison sentence in an internment camp. But dangers await at every part of the trip. When Lee Ga-yeon approached the border with Laos on a full bus, police started to check IDs. Her heart started beating fast and her legs shaking out of fear. Luckily, the Korean Chinese woman sitting next to her firmly told her to stop and slapped her leg so hard that she momentarily regained her composure. She believes those few seconds probably saved her life. After getting into Laos, the trip was far from over; she still had to cross the dangerous Mekong river to Thailand where she

would be detained for a certain time before she was eventually be sent to South Korea through diplomatic channels.

Lee Gao-yeon grew up firmly believing that South Korea was a poor country with no freedom or education. Upon her arrival in the South, she was shocked to find the complete opposite. Now she finally feels free to get the education she dreamed about as child.

Choi Seong-Guk

Choi Seong-Guk wanted to be part of the North Korean elite to date the girl of his dreams. But he was neither rich nor well connected. When South Korean dramas became very popular on the North Korean black market he saw an opportunity. After 8 years working at Pyongyang’s premier animation studio, he decided to become an entrepreneur. At first, he smuggled South Korean DVDs and computer parts but quickly he started putting his computer skills to use on a much more creative business idea. He set up a small portrait studio where customers could replace the actors’ faces on popular forbidden tv drama screen-grabs with their own. This idea proved successful and very lucrative. He soon managed to make enough money to open one of Pyongyang’s first computer rooms.

The process of registering a business in North Korea is quite intense; he had to write a business plan promoting the Juche and the Party and donate 2 million won to the Government, gesture for which he even received the Kim Il Sung North Korean youth honor award. While officially promoting the Party, the computer room was in fact a place to play online games and watch Korean dramas. In 2006, he was arrested for smuggling movies. The offense was very serious but as some of his customers were influential government officials he was let off lightly. However, he had to be sent away from the capital and suddenly, his whole work had been for nothing. He would not get the girl of his dreams.

Disillusioned, this is the moment Choi Seong-Guk decided to defect to the South. Since his defection, Choi Seong-Guk has gone back to his early studio days and started to draw cartoons describing the struggles of the North Korean life. Although he left North Korea and the dictatorial rules of the North Korean regime behind, the dating rules in South Korea proved not so different after all. Even here, you will still have better chance if you are part of the elite, and you are better off making more money to be part of it!