INSPIRATION

Capturing the Urban Condition

INSPIRATIONAL URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS

Inspirational Urban Photography

“A city is more than a place in space. It is a drama in time.” – Patrick Geddes

Our cities are a microcosm of the human condition – home to the full gamut of human emotion. They can be seen as places of possibility, of energy, adventure and opportunity, but also as overwhelming and unnatural, constraining and suffocating.

It is therefore no surprise that cities are the setting for the work of many of the most celebrated photographers since the technology’s inception. Diane Arbus, Weegee, Joel Meyerowitz, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Karl Hugo Schmolz and countless others have used the urban environment as their canvas.

And today, with so many of us living in cities, it has never been easier to get outside and find inspiration on the streets. But of course with so many street and architectural photographers, how you can show a new perspective, tell a new story?

This list highlights a few of my favourite photographers who work, or worked in the urban environment. They each approach the city from a different viewpoint, and with a different motive, but are united in their ability to create wonderful, evocative art. I hope you find a wealth of inspiration, and a few surprises among these names.

(Banner image © Martin Roemers)

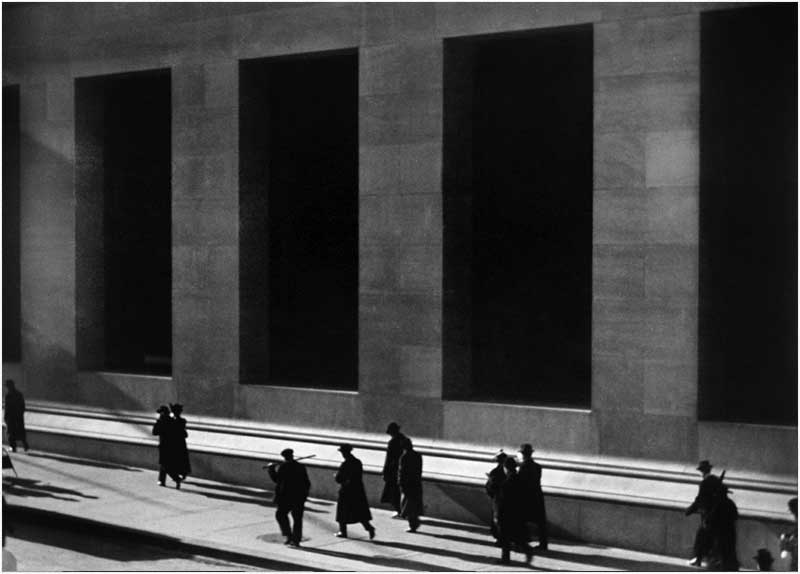

(Alfred Stieglitz and) Paul Strand (United States)

Images © Paul Strand

“The artist’s world is limitless. It can be found anywhere, far from where he lives or a few feet away. It is always on his doorstep”. – Paul Strand

It’s a strange thought now, but there was a time when photography was seen as a purely technical craft – a form of precise documentation that was derided by academics and institutions. Photographers were largely considered as technicians, rather than artists. Photography was pictorial and representative, rather than abstract or emotive.

The photographer generally credited with changing that idea was Alfred Stieglitz. He argued that photography could be artful – documents of a photographer’s individual perception rather than merely accurate representation – and that photography should be appreciated in museums and galleries, side by side with paintings and sculpture. That idea was unanimously rejected by the mainstream, and so he forged a path of his own, opening up a tiny museum with the aim of promoting photography as a fine art form.

Paul Strand visited that gallery while still in school, and it profoundly changed him. Leaving through its entrance doors he knew that he wanted to dedicate his life to photography, and over time he and Stieglitz developed a close relationship – Stieglitz acting as Strand’s mentor and champion.

Strand had already been one of the pioneers of candid street photography, employing an ingenious, if morally questionable, technique to capture objective, rather than posed documents of New York street life. He attached a false lens to his camera, perpendicular to the real one, and would pretend to shoot in one direction while capturing stealth portraits in another. But under Stieglitz his work became more abstract – exploring the geometries of architecture and its relationship to humans through form and shadow, unusual viewpoints and tight compositions.

Over time perceptions have changed, and they are now both considers pioneers of American Modernism. But what made both photographers so special was that they simplified photography. With Strand for example, he used close framing and strange angles to create visual gaps that the viewer had to fill. He forced the onlooker to contemplate what they were seeing, or rather, what they were feeling. His abstract urban images put across an ephemeral sense of life in transience. We recognise elements of ourselves in them, despite them being incomplete, their meaning concealed.

Photography had never really been considered like that before – as a form of art that the viewer can feel as much as they see.

Matt Stuart (UK)

Images © Matt Stuart

“The craziest stuff is the stuff that is generally real and the stuff you can make up is less impressive”. – Matt Stuart

You could argue that street photography is photography at its purest – spontaneous and free, no studio or poses. Stuart practices the genre at its most candid, finding witty and quirky unplanned moments that disappear as quickly as they form. Blink and you miss it. There’s no deep meaning in his work, just memorable, genuine snapshots of the world aligning in weird and wonderful ways. And he shoots entirely analogue, citing the fact that it allows him to adjust focus (making use of a concept called ‘hyperfocal distance’) faster than any digital auto-focusing camera can.

He uses the urban environment to his advantage – candid street photography requires patience and dedication, and the more complex and frenetic the environment, the more happy interactions that occur. That plus it’s easier to operate unnoticed in a busy, people-filled setting.

Stuart finds and celebrates the fleeting flashes of colour, literal and figurative, in the banal. Those “how did he spot that?” moments. Beautiful serendipity, belying patience and technique.

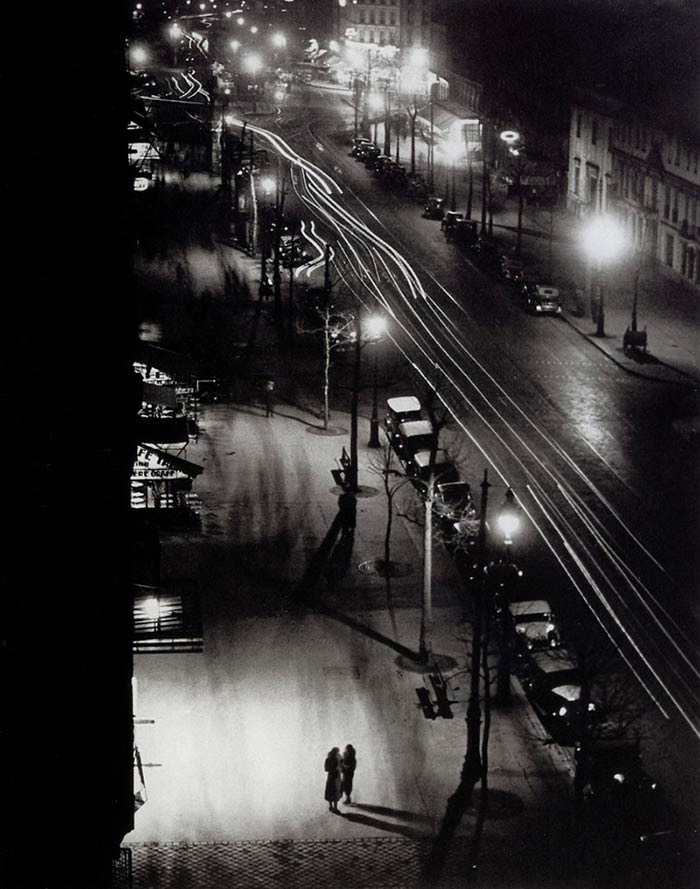

Brassaï (Hungary)

Images © Brassaï

“Night does not show things, it suggests them. It disturbs and surprises us with its strangeness. It liberates forces within us which are dominated by our reason during the daytime.” – Brassaï

Brassaï, a pseudonym for Hungarian photographer Gyula Halász, emigrated to Paris in the 1920s, and rose to international fame with his photography, pioneering the art of night-time image making, and cementing the myth of Paris as a bohemian metropolis with his fog-drenched images of Montmartre, the Eiffel tower against a midnight sky, and the casual cafes of Longchamps.

But his work wasn’t all so wistful. He made his mark with his 1933 book ‘Paris de Nuit’, juxtaposing luminous, dreamlike nightscapes with contemporary documentary images of those roaming the streets at night – prostitutes, transvestites and hoodlums occupying opium dens and cheap music halls. His images were a technical marvel – pushing the boundaries of what was possible with a camera at the time. And the subject matter was progressive – few had turned their lenses to the underbelly of society before him.

His use of contrasting light and darkness, and of fog as a tool to create atmosphere, paved the way for generations of night-time photographers to come.

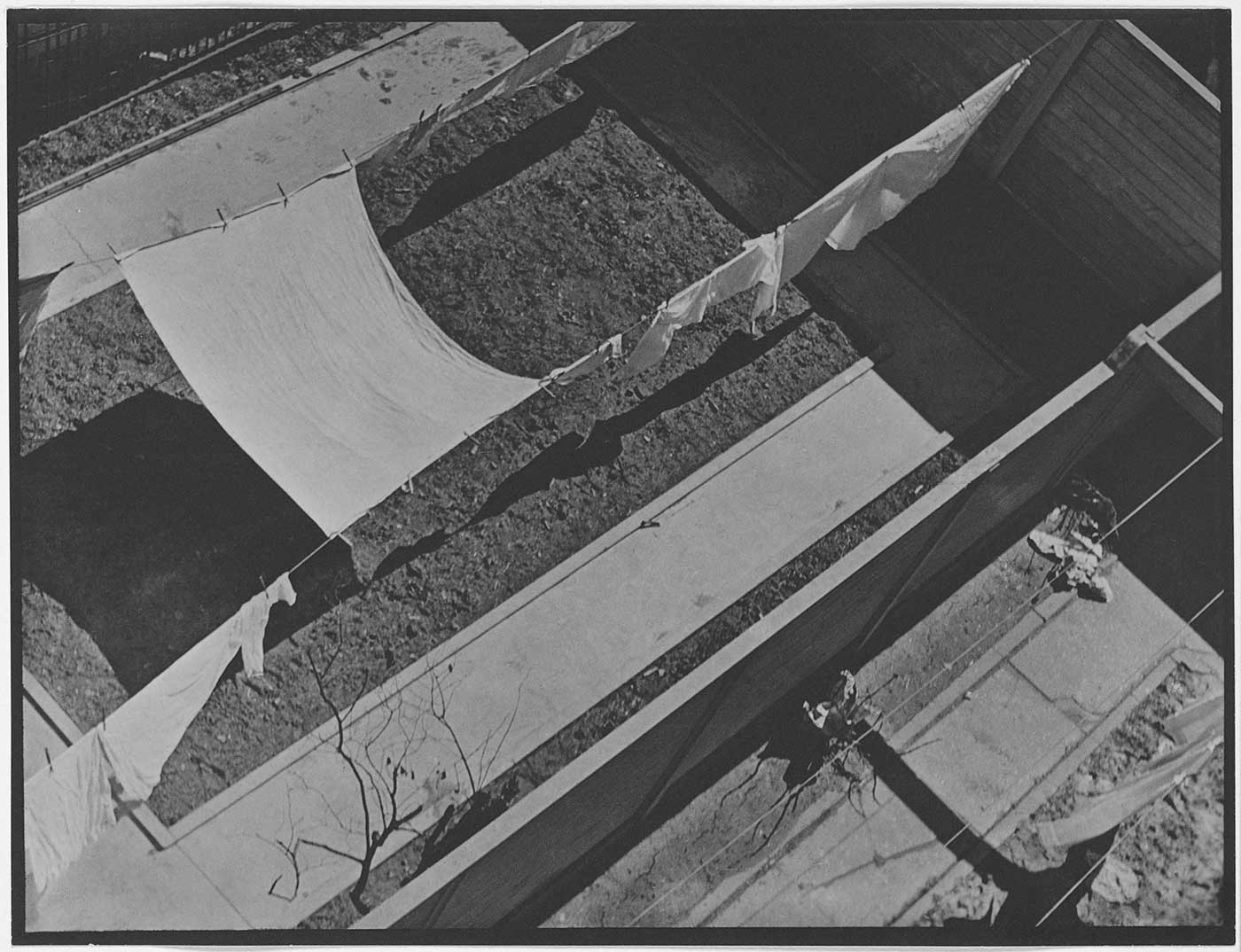

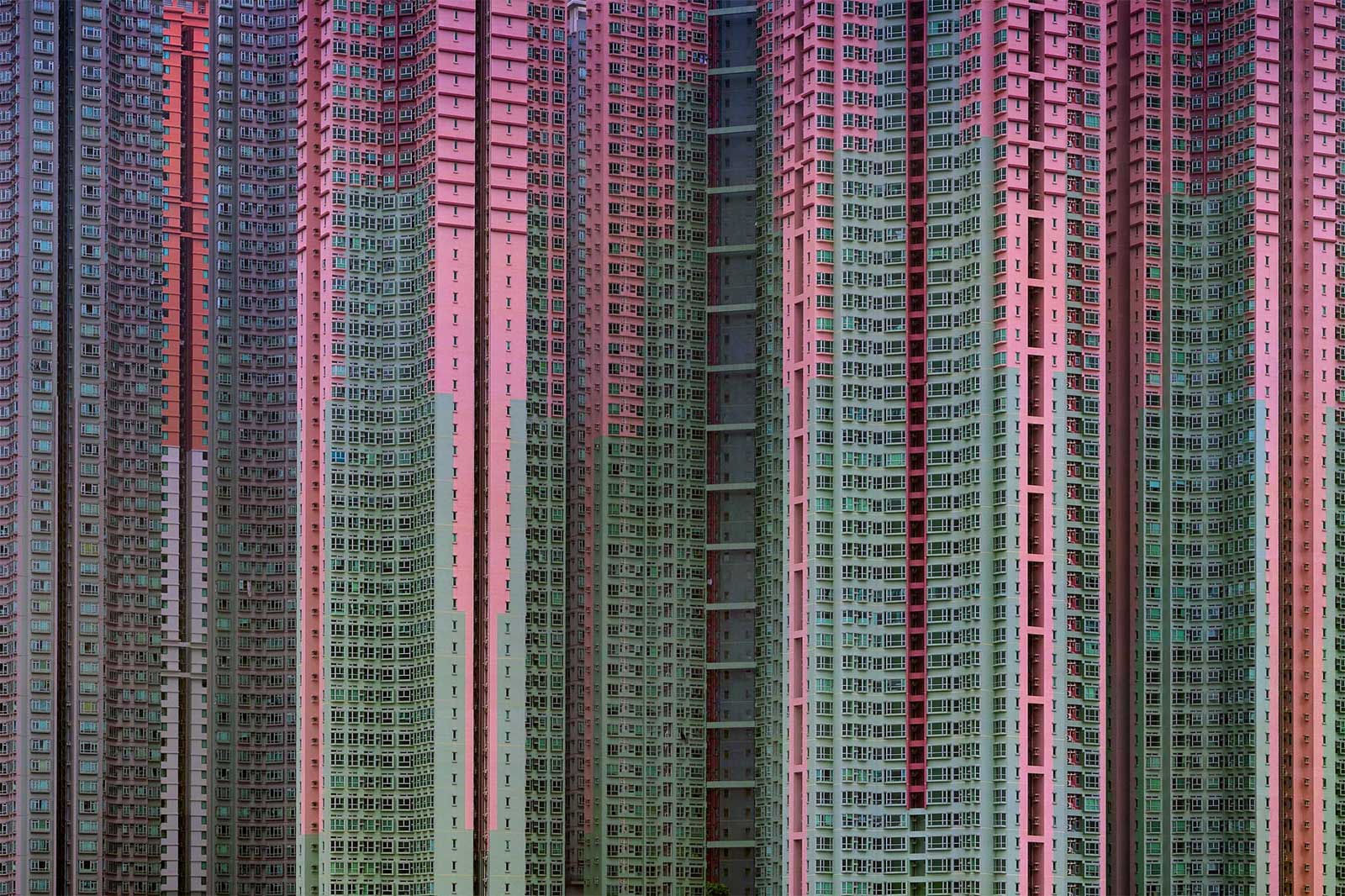

Michael Wolf (Germany)

Images © Michael Wolf

Few modern photographers have captured the urban condition like Wolf. Since the early 2000s when he left the world of photojournalism (something that had in his words become “stupid and boring”) to focus on fine art, he has dedicated his work to exploring life in our megacities – what it means to live in urban environments and how they can often completely overwhelm the humanity within.

He’s perhaps best known for his series ‘Architecture of Density’, through which he examined the dizzying scale and density of Hong Kong through abstracted images of architecture. By focussing on patterns of architectural geometry, with building facades bleeding off the frame in all directions, he creates an unsettling representation of urban life – vast, repetitive and soulless. On closer inspection though, the trappings of people are visible. Possessions can be seen through windows, laundry hangs off balconies, and window boxes and hanging plants hint at the human – the irregularities that exist in an otherwise ordered world.

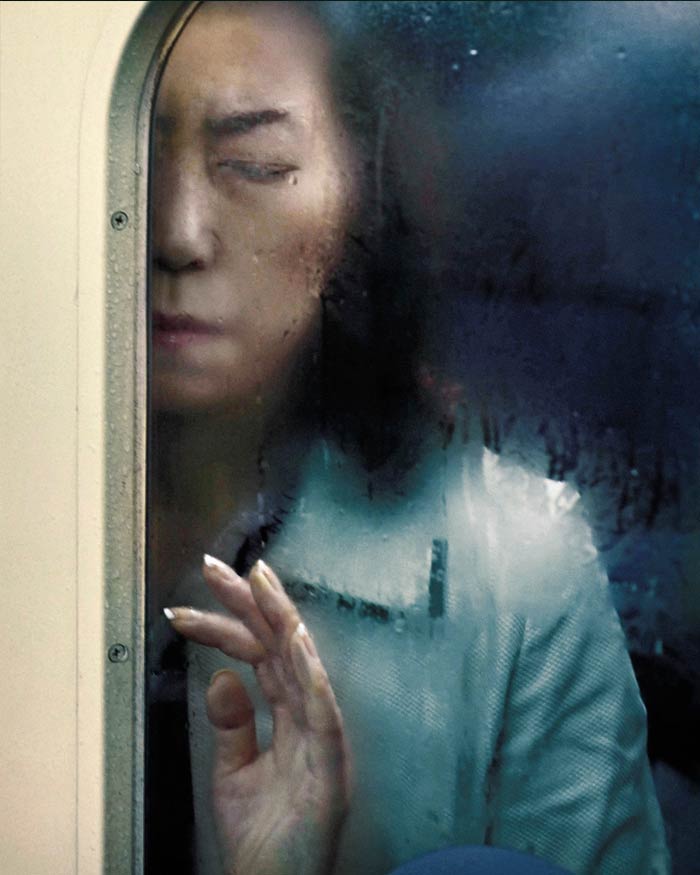

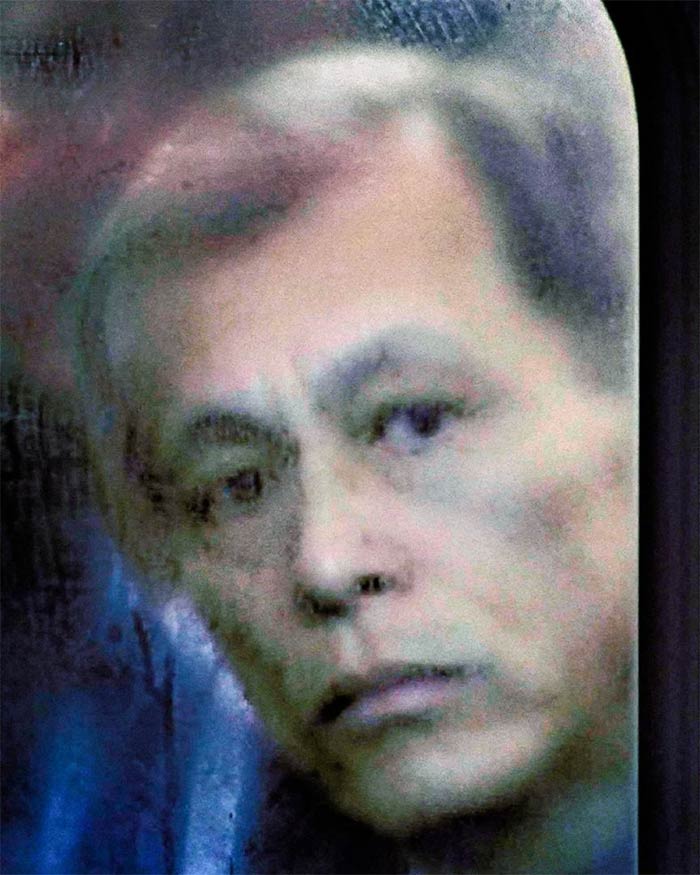

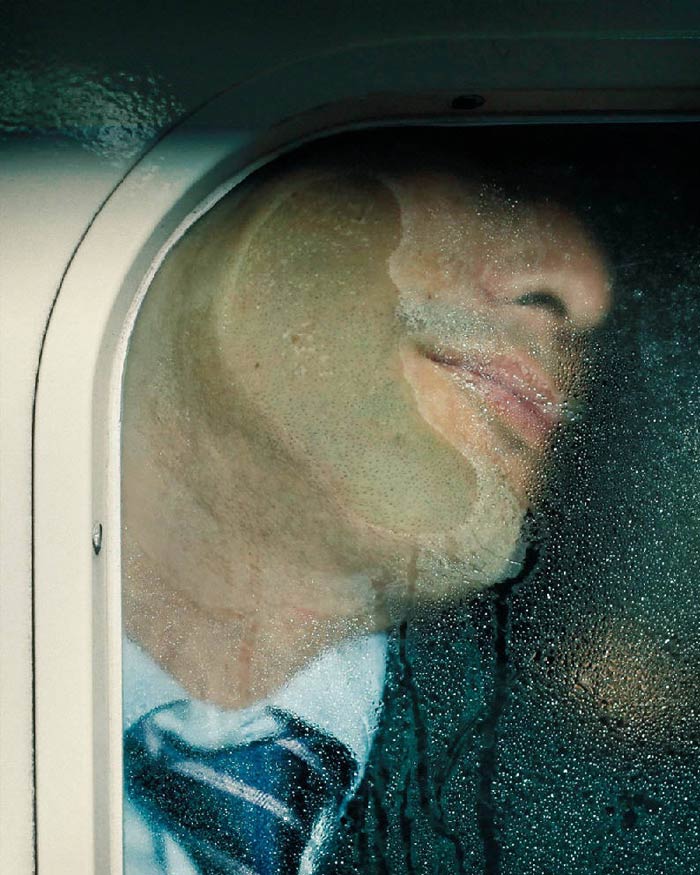

His series ‘Tokyo Compression’ explores similar themes – of oppression, and of how the modern world can force us into spaces that we shouldn’t fit (this time a little more literally!). His candid images of Japanese commuters squeezed onto trains in rush hour are visceral and suffocating, in his words highlighting “their complete vulnerability to the city at its most extreme”.

In other series he peers through the windows of apartment blocks, and finds absurd views on Google street view, but each body of work shares a poignancy – a foreboding quality of life in cities being anything but the utopia it is so often sold as. An unnatural fit for a species that is losing its connection with the wild. The impression though is one of us surviving, rather than thriving.

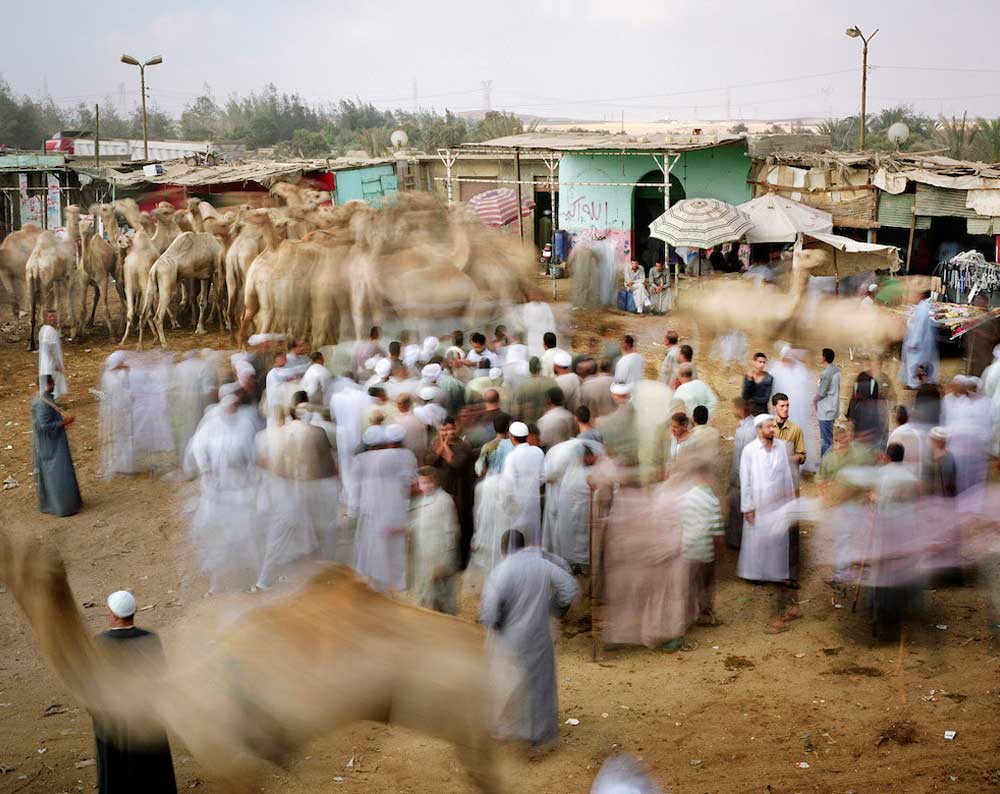

Martin Roemers (The Netherlands)

Images © Martin Roemers

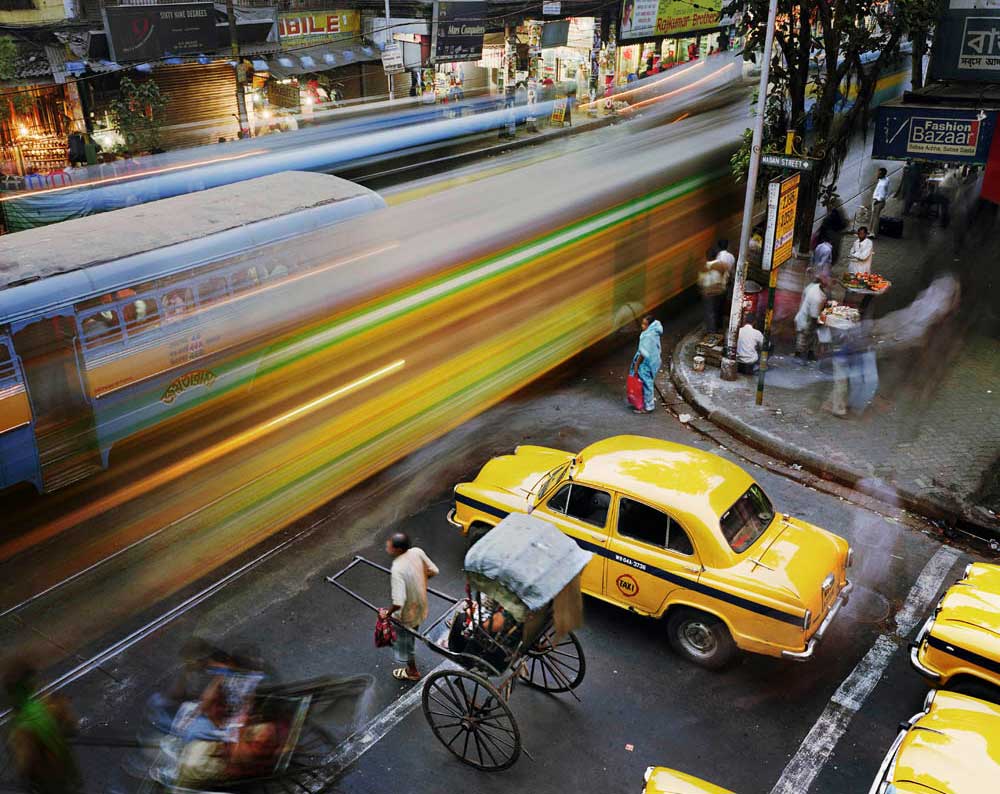

Like Michael Wolf, Roemers is fascinated by megacities – places like Mumbai, Lagos and New York. His project ‘Metropolis’ started with a simple question: how can you depict in single images the boundless, almost tangible energy and chaos of a city? His answer is to focus on city hubs – road junctions, market places, transport interchanges – and use a distant, often elevated position and slow shutter speed to capture the endless stream of movement, the fizz and crackle of thousands of people going about their daily business.

It’s a simple concept, beautifully realised. Each frame is carefully composed and highly stylised, pulsing with the interactions between static and dynamic forces. But unlike Wolf, his images come from a brighter place, capturing how people overrun their cities, rather than the other way round. They overflow with humanity – the lifeblood of our cities that make them what they are.

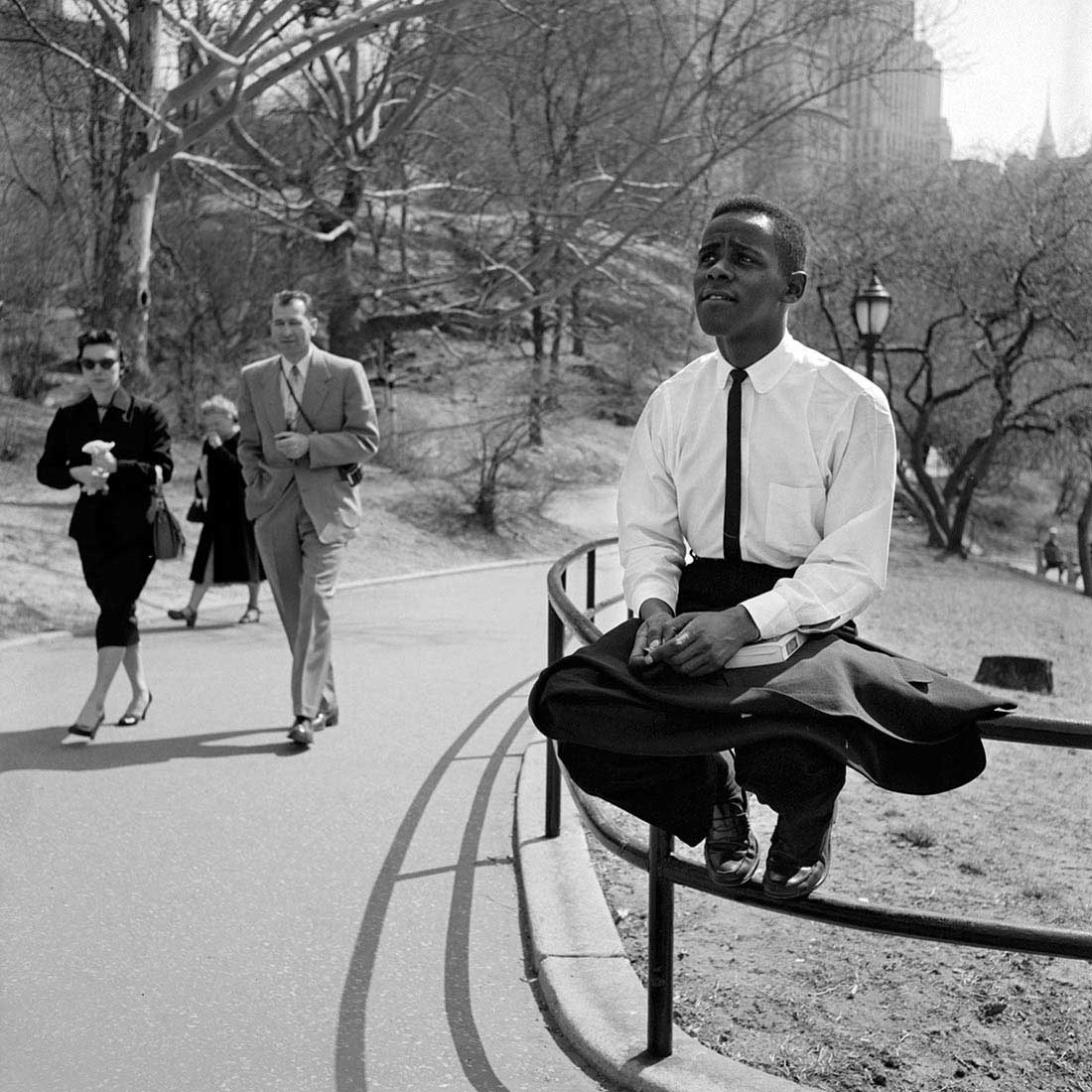

Vivian Maier (United States)

Images © Vivian Maier

No urban photography list would be complete without Maier. Those not familiar with her story would do well to watch the documentary ‘Finding Vivian Maier’ – a wonderful tale of a Chicago nanny, quietly obsessed with photography, whose work has only been ‘discovered’ and celebrated posthumously.

The story may make for great drama (and there are dark undertones to it that add an intriguing moral complexity) but it would be insignificant were it not for her wonderful gift for photography. She had an incredible eye for composition and atmosphere, and her images are imbued with a deep humanity, and an impartial eye – she photographed everyone from street kids and the elderly on the fringes of society, to rich and glamorous women shopping on North Michigan Avenue. That she was so unassuming enabled her to go unnoticed as she documented the full spectrum of life in her home city.