FEATURED STORY

In the Mind’s Eye: Working in Large Format

BY JOHN SANDERSON

The making of an award-winning photograph on Florida’s Gulf Coast

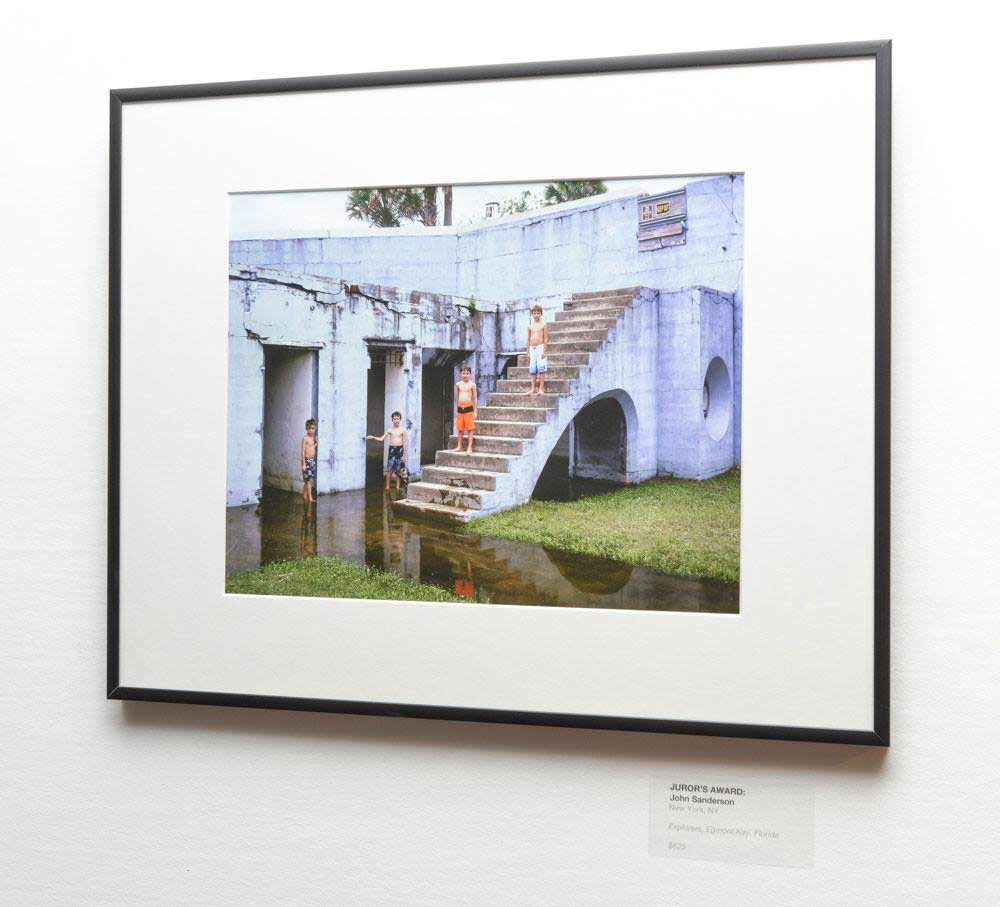

My image ‘Explorers, Egmont Key, Florida’ was recently selected for Life Framer’s Youthhood theme judged by acclaimed commercial and fine art photographer David Stewart, having also won Juror’s Choice at the PhotoPlace Gallery ‘Man in the Landscape’ award. I was honored at the eloquence regarding the picture written in his juror’s statement:

“John’s image is eye-catching – there’s a strong composition, a gorgeous palette of colours, and the four boys, stood unnaturally ordered and regimented. As I see it, there’s almost a ‘Lord of the Flies’ feeling about it, something a little unsettling about the way they seem to rule this strange, dangerous environment. That juxtaposition of bright colours and darker ideas works very well. By getting the boys to stop and pose across the frame, rather than just spontaneously capturing them playing, John creates something arresting and interesting – more than just an attractive image.”

I firmly believe it isn’t a picture I could have made using a smaller format, and this article explains a little about why.

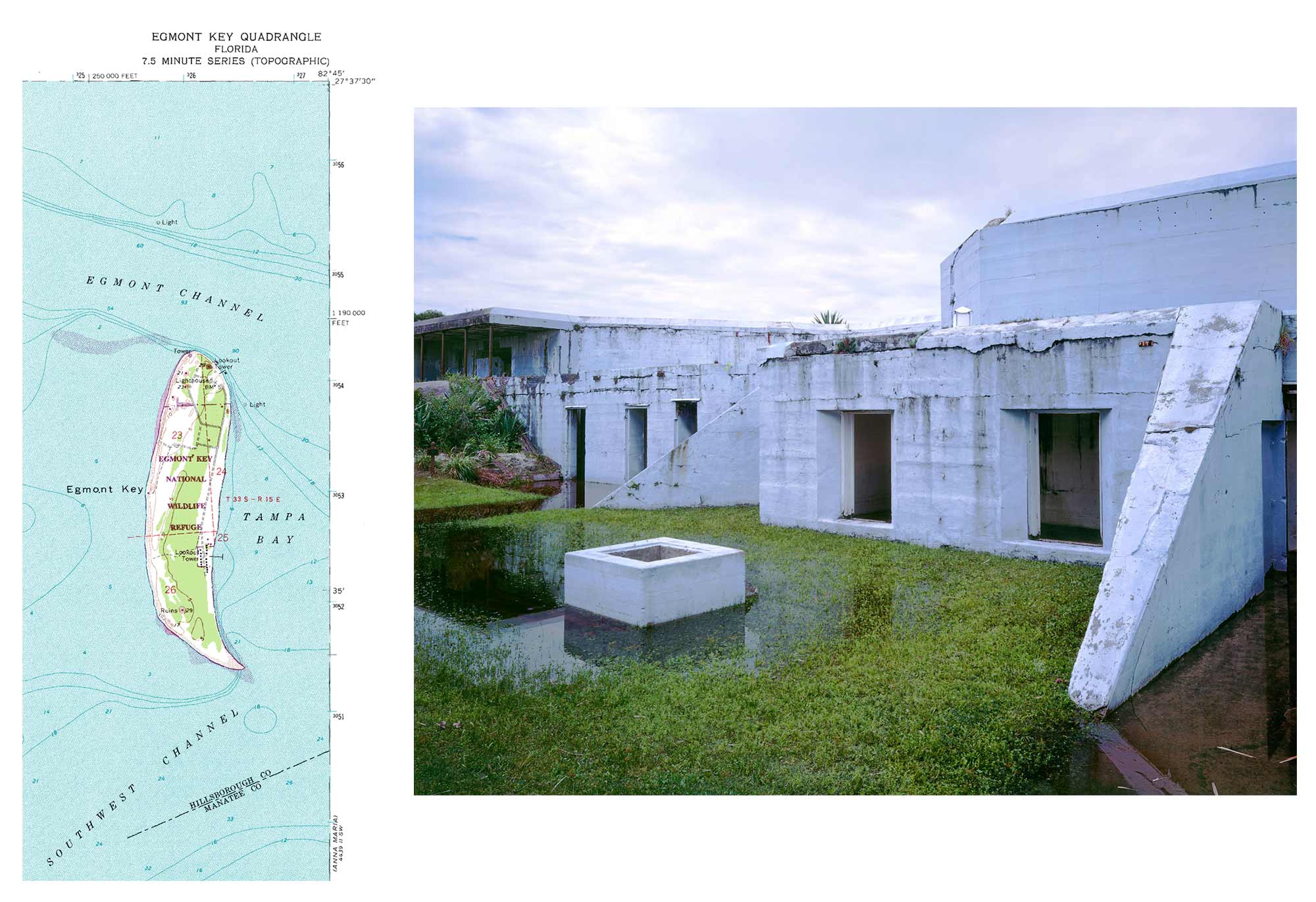

It all began with a location…

The historic Battery McIntosh, which once housed coastal artillery for the U.S. Navy is situated on Egmont Key, a small island off the coast of Florida. The structure seen in the picture was the first thing to strike my attention. The stripped down quality appealed to me in the same way many other ruins have, their archaic quality illustrating a past in which constructed objects are designed in such a way as to reveal curiosities of shape, and mystery. It’s a highly geometric structure, including not only rectangular entrance ways but a circular opening which, when placed next to the boys, softens the image. In my photographs I often depict structural subjects which have what I call a “hard edge”, usually very angular and defined by their shape. And certainly, this image without the boys would affect a harsher, colder, and more austere relationship, yet the inclusion of the children softens this edge, elevating the picture beyond the documentary and into the poetic realm.

My original intent was to photograph without the human element, since its design intrigued me and the flooded floor’s reflective detail seemed to be enough to carry the impact of the picture, but as I set up the 8×10” camera, I felt something was missing. So I waited. As I did so, several other people visited the location in front of my camera and as I observed them my discontent with my original rendering grew — this image needed a human element to complete it. I continued to leave my camera set up, ready to expose a sheet of film. All I needed was to find a subject not only willing to be in the picture, but one that would help reinforce the meaning which I was hoping to convey. A counterpoint to the harder architectural element.

The battery is connected with another fortification on the island with a long brick path which runs in a clear line for about 150 feet. It was down this line that I peered for the arrival of a subject to complete the scene. After about an hour waiting in the Florida sun, four boys arrived at the southern end of the fortification and were intrigued with the building. They started to climb inside, and were wary at first before stepping into the flooded ground, but soon fear gave way to curiosity and they walked through the tadpole-laden water with nonchalance. I saw in their excitement my own curiosity for this place. There was a certain empathy between myself and the subject here.

So the counterpoint, my subject, arrived in the form of four boys. There wasn’t much positioning required. They fell naturally into the scene, because it is a place where they were engaged, and in wonder. I exposed the scene on an 8×10” sheet of Kodak Ektachrome film, thanked the boys, and off they went, as quickly and spiritedly as they arrived”.

Using the large-format 8×10 camera…

The above image shows the camera setup for the Explorers image – an Arca Swiss 8×10″ large format film camera. I made a claim at the beginning of this article that I would not have made this picture with a smaller format camera. While I’ve spent years photographing with large format and I can safely say I’m comfortable with their operation (plus increased weight and bulk) I will briefly explain why I think this is so.

Photographing with intention

For most applications the large format camera requires the use of a tripod. This slows you down. The larger film size requires a commensurate increase in f/stop, which in turn lowers the shutter speed — you lose the ability to capture action, or what Henri Cartier-Bresson termed “the decisive moment.” A sensitivity towards stillness of mind and image begins to develop, both in the photographer and his process. Because of the camera weight and completely manual camera operation involved before exposing film, one begins working in a state of accumulated intentions.

What this means is simple, I tend to do a lot of the compositional, conceptual and camera placement deliberations “in the mind’s eye”, as Ansel Adams would say, prior to photographing. Naturally, one could use a smaller format camera with the same cautioned slowness of large format, but I would argue the inherent qualities of the latter (large print sizes, color tonality, smoothness of grain) to be of greater benefit when working with the typical, unmoving subjects of a large format photographer.

Composing with large format

Peering through an 8×10” gridded ground glass, as opposed to a tiny viewfinder, opens me up to noticing details. In recent conversation, photographer Yoav Friedlander remarked on the triangular element of grass jutting up from below the frame. Since it’s not pointedly directed out of the corner of the frame but rather offset slightly from the corner, he said, its presence softens the image. He suggested it worked well in balancing the composition. While I agree with his observation, I must admit the choice was not long though out but rather done instinctively.

I can only speak from my own experience. It would be hubris to claim my method is better than another photographer’s. That said, the imposed slowness of the format has its limitations. Though not too often, I have missed certain shots because of weather, wind moving the camera, or being slow to set the camera up (see Ansel Adams’ anecdote about his photograph Moonrise, Hernandez). At least for the work I do, the benefits outweigh any drawbacks. The deliberative approach makes me consider — deeply — what it is I’m doing out there in the field.

“…four boys trapped in the geometric wasteland of fecund runoff and concrete, their gazes trapping me within the image, haunted me most. It asks questions of humanity and progress, of inheritance, and of exclusion. And yet it is beautiful in its balance, its forms, and its color. It is truly Poetic.”

– Juror Brett L. Erickson’s Award, PhotoPlace Gallery Man in the Landscape Exhibition

All images and text © John Sanderson

See more of his work at www.john-sanderson.com