INSPIRATION

Life and Death on a Table Top

INSPIRATIONAL STILL LIFE PHOTOGRAPHERS

Pushing the still life genre forwards

Still life has always been about more than fruit and flowers arranged on tables. The French word for the genre – nature morte – references mortality, a nod to the brevity of even the most luxurious of lives. Still life images at their best illicit a response on both a visual and an intellectual level – both examining the principles of arrangement and aesthetic taste, and asking questions about commodity-based status, the everyday, and life and death. They take the ordinary and make it extraordinary. Everyday objects morphed into high art.

With any genre rooted in such tradition though, it takes special work to push it in new and interesting directions – for the work to feel fresh and exciting, rather than just referential and appropriated. An aesthetic document is one thing, but what does a modern still life communicate that we don’t already know, that photographers weren’t already exploring almost a century ago?

This list highlights a few of my favourite photographers who work with the still life genre, as well as a couple of the pioneers. They each approach the genre from a different place, but are united in their ability to create beautiful, meaningful art. I hope you find a wealth of inspiration, and a few surprises among these names.

(Banner image © Sharon Core)

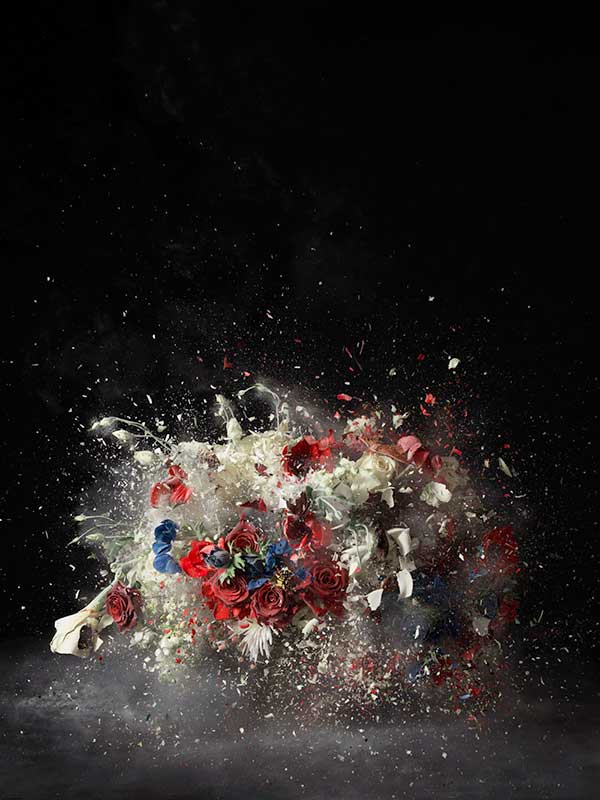

Ori Gersht (Israel)

Images © Ori Gersht

Gersht is known for his ‘still life explosions’ – a delicious oxymoron to describe his process of capturing objects in suspension as they shatter into thousands of pieces. It’s a subversive play on the traditional still life genre that’s made more wryly rebellious in how he chooses classic still life subject matter like flowers and fruits, and frames them in dark, softly lit settings that mimic the Baroque painters of the 1600s like Juan Sánchez Cotán.

He uses modern camera to freeze information that happens too quickly for the human eye to process – something which we would be otherwise unable to experience. It’s what Walter Benjamin referred to as the ‘optical unconsciousness’ in his seminal essay ‘A Short History of Photography’.

What I love about Gersht’s work is the interplay of contrasting elements – the scenes are a document of both peace (flowers being a symbol of such) and destruction. They are both grotesque and attractive. Traditional and modern. A view of life and the inevitability of death. It’s a beautifully simple concept, executed with elegance.

Wolfgang Tillmans (Germany)

Images © Wolfgang Tillmans

Fine-art photographer Tillmans has spent a career redefining photographic practice and representation. He emerged in the 1990s documenting the youthful European counterculture he was a part of, and has been challenging the distinction between low and high culture ever since – balancing on a fragile creative equilibrium between low-key observation, and virtuosic practise shaped by a deep knowledge of the history of art. Whether he’s photographing abstractions of light, or exhibiting photocopied images of piles of litter, his work is born of an obsessive need to document. He puts it simply himself: “I take pictures, in order to see the world.”

Still life is a genre he has frequently returned to, one of the most celebrated examples being ‘Night Still Life’. What at first looks like a mundane snapshot of everyday objects reveals more on further study – there’s a sophisticated structure of form and colour. The batteries, scale and gold are all modern versions of objects used in still life art historically. Elements of the image subtly nod to the photographic process itself.

He may be best known for his avant-garde curation – scotch-taping images to walls, displaying tiny prints at shin height – but ultimately ‘Night Still Life’ is one of many examples of what Tillmans continues to do: challenge our perceptions of art.

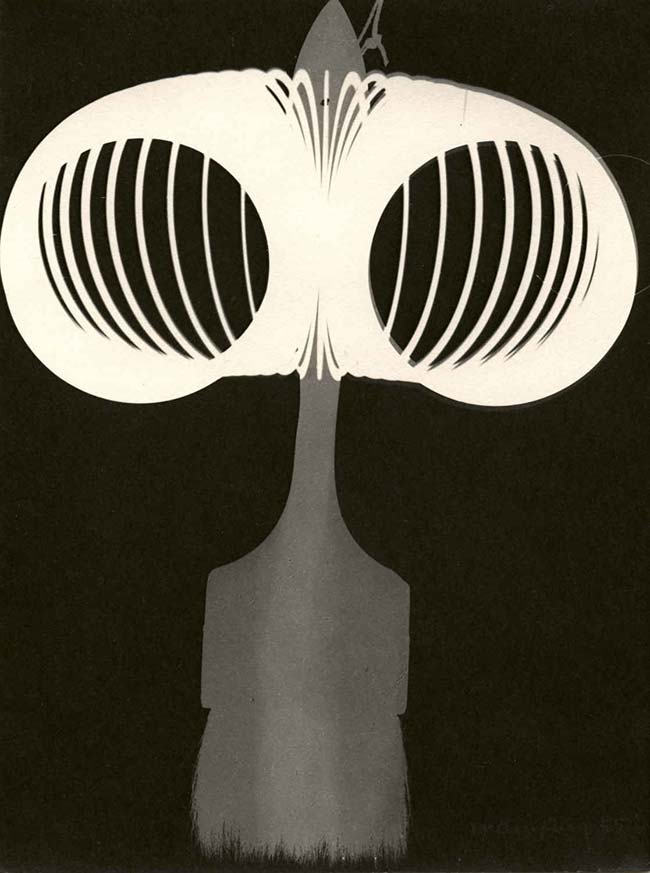

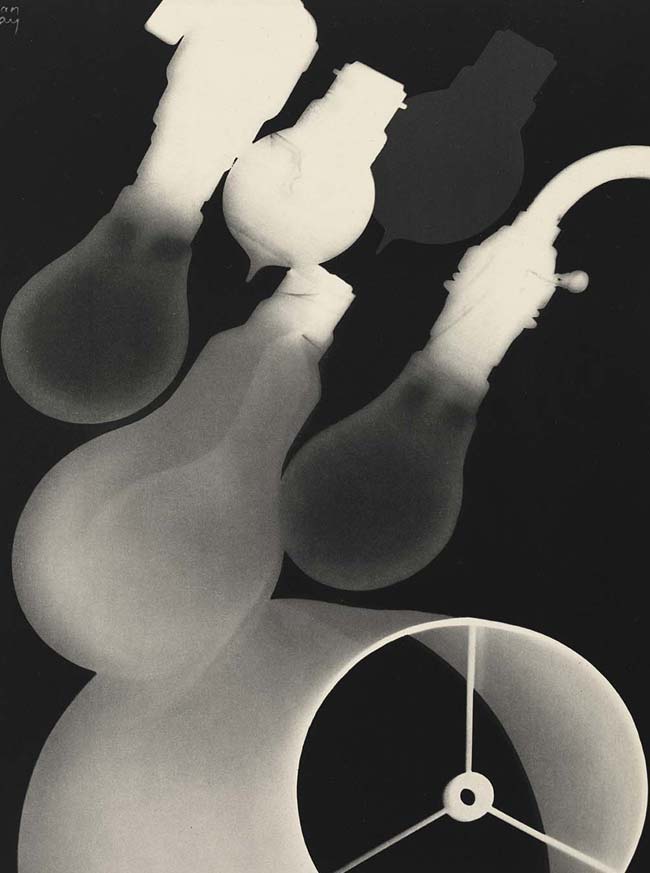

Man Ray (United States)

Images © Man Ray

Man Ray could inhabit any number of genre lists – such was his ability to make iconic work in whatever style he chose. He was also a true innovator and much of his still life work used his self-named and visionary “Rayograph” technique – a camera-less method he accidently discovered (albeit not being the first) in the dark room whereby he would place objects directly onto sheets of photosensitized paper and expose them to light. He had taken many more conventional still life images before, but these rayographs revealed a new way of seeing, falling somewhere between the abstract and the representational. Commonplace objects morphing into something dreamlike.

For me they strike a chord with their graphic purity. A visual simplicity that was so rare at the time. Nowadays, we see this kind of imagery much more commonly – I always think of them when my bag passes through the scanners at an airport! – but Man Ray was a true pioneer.

Sharon Core (United States)

Images © Sharon Core

Core is a curious artist. Her work has always been about precise recreations of other artists – contemporary artist Wayne Thiebaud’s famous cake paintings, or 18th century oil painter Raphaelle Peale’s compositions of flowers – but it would be an injustice to call her a copycat. Her painstaking photographic reproductions are masterful examples of sleight-of-hand and rigor, and are themselves conceptually fascinating – turning paintings that aspire to realism, into photographs that aspire to painting. Her renderings of paintings as photographs recognises their non-identity, even if they may look identical.

In her series Early American she again uses Raphaelle Peale as a starting point, recreating his still life images of fruits and vegetables. Her compositions are rich and opulent, much like Peale’s but what I love is how they engage on a parallel intellectual level. Photography might be seen as inferior to painting, as photographs lack an ‘aura’ – the ease and speed with which they can be taken (especially now) is opposed to the toil and labour associated with applying paint to canvas. But Core inverts that in her meticulous approach: “I researched and collected period porcelain and glass and grew, from heirloom seeds, varieties of fruits and vegetables in existence in the early 19th century”. What may have taken Peale hours, is nothing compared to the process of growing fruits from seed.

What strikes me about all of her work is that her reproductions of paintings may look identical to their originals, but carry such different ideas due to the differences in time, place and technology. They represent a whole host of new ideas – mechanical, intellectual, cultural – despite on first glance being difficult to distinguish from one another.

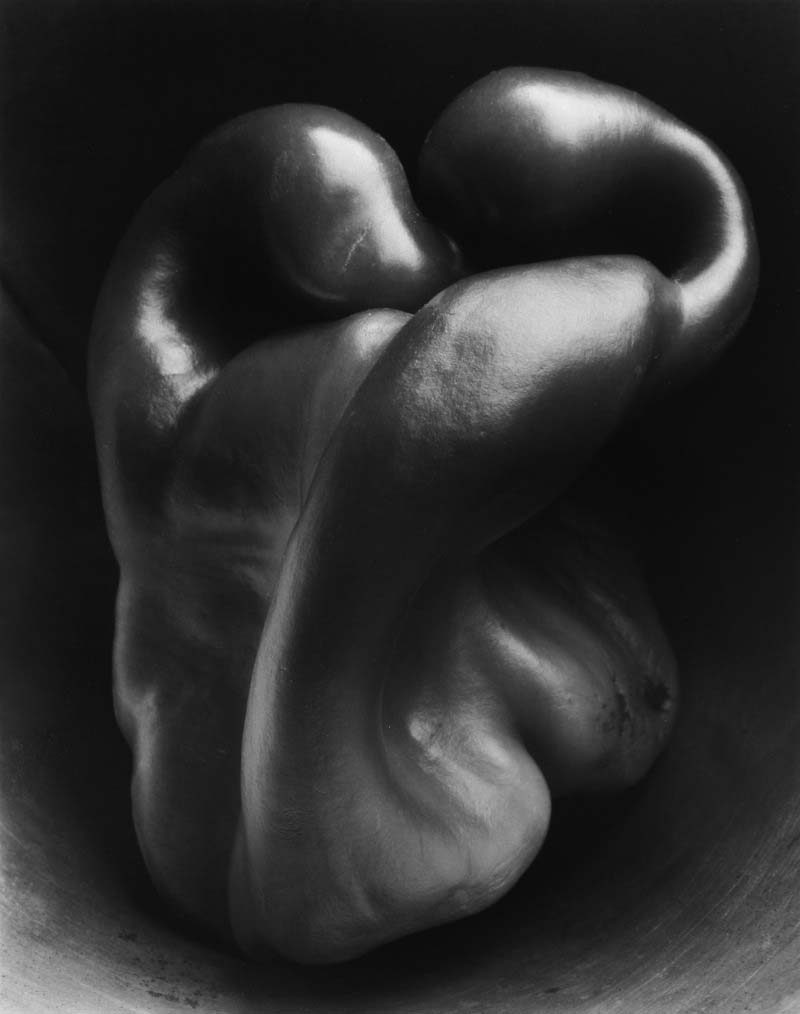

Edward Weston (United States)

Images © Edward Weston

Weston has been described as one of the greatest American photographers of his generation, credited with helping to take photography out of the Victorian age, where it was seen as nothing more than an addendum to painting, which itself was seen as something for the privileged. His approach was democratic, in his own words trying “to make the commonplace unusual”. It’s something that has informed so much photographic practice since.

In his still life images, there’s a scrupulous rendering of tone, giving each object a heightened presence. One of his most celebrated examples of this is an image of a humble green pepper, which through his lens takes on a modernist quality – all attention on form and texture. He captured the essence of objects, and in doing so helped redefine what photography could be. So many photographers are indebted to his thinking in one way or another, whether they’re aware of it or not.

Lorenzo Vitturi (Italy)

Images © Lorenzo Vitturi

Vitturi’s work is difficult to define, occupying a space between photography, sculpture and theatre. He makes colourful representations (“handmade visions” as he calls them) of often dark themes, packed full of both ideas and visual interest.

We’ve already featured his Dalston Anatomy project, but each of his series is worthy of attention. Whereas Dalston Anatomy examined the cultural mixing pot, and decline due to gentrification, of Ridley Road Market in East London, Anthropocene comes from a much more esoteric place – a reflection on the relationship between man and nature. Up until the 20th century, artists represented nature as unspoiled and pure spaces but only 100 years later it has proved to be a fragile system under the control of a destructive mankind. Vitturi wrestles with how we can depict man and nature together in art.

The resulting images of his site-specific installation are dark and menacing. His sculptures, meticulously crafted from building materials, natural pigments and fake fauna, are moody and dystopian. Plants cling on to life in harsh environments not designed to support them, splashed with coloured powders that call to mind industrial painting processes. The scenes are a visual treat, and emotionally evocative – difficult to fully decipher but connecting on a guttural level. It’s another unique vision from a one-of-a-kind artist.